After years, decades, and in the case of Sweden, even centuries of neutrality Sweden and Finland decided to apply for NATO membership shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine earlier this year. What does this mean for the Atlantic Alliance and what can these two Nordic countries bring to the table? The Militaire Spectator spoke with Finnish security and defence expert Tomas Ries of the Swedish Defence University about Finland and Sweden’s prospective NATO membership.

First, the fundamentals: applying for NATO membership was a ‘dramatic move by Finland’, according to Ries since Finland’s government had been reticent about raising this option in the three decades following the end of the Cold War, whereas Sweden used to have ‘a more open popular discussion about joining NATO.’ The Finnish announcement came so soon after Russia’s attack on Ukraine that it is clear that Finland already had a plan for application available. Sweden and Finland always stated that if they were to join NATO, they would do it together. However, ‘the Finnish decision took Stockholm completely by surprise’, Ries says, and ‘at first the application of the two countries was not coordinated at all.’ Afterwards, ‘Finland did everything it could to involve its neighbour in the process, to bring Sweden onboard.’

Finland and Sweden will join NATO as contributors. Photo NATO

Idealists and realists become NATO members

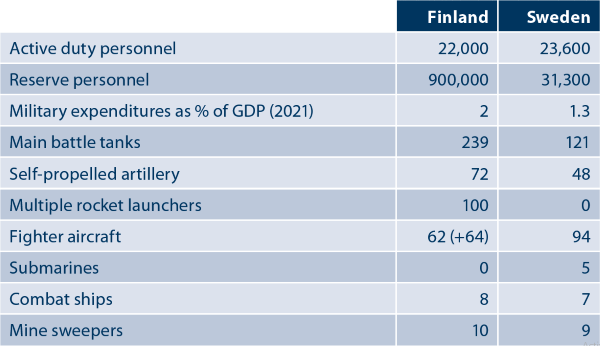

Based on his experience, Ries felt that part of Finland’s foreign and security policy professionals in the MFA, MOD and Defence Forces increasingly supported NATO membership, in contrast to the general population whose support for membership hovered around 20-25 per cent. According to Ries, the general notion was, however, that once ‘political leaders would speak up in favour of NATO, the population would soon follow’. And that is just what happened after Russia’s attack on Ukraine. Popular support for NATO membership rose to 68 per cent just after Russia started its war. Within three weeks support went up even to 80 per cent. What is the explanation for this dramatic shift of public opinion? At its core, ‘Finland’s worldview in foreign affairs is one of realpolitik’, Ries explains. The country has always ‘remained wary of Russian intentions, even after the Cold War had ended.’ It kept Finland’s very large Armed Forces and Civil Defence intact instead of reaping the rewards of the ‘peace dividend’ as was invariably the case in other European NATO countries. In terms of quantity Finland today actually fields the largest and best-prepared armed forces in Europe, despite its relatively small population.

Sweden has had a different experience altogether. Here, Ries recalls, ‘support for NATO membership is now about 58 per cent, which is quite low, all things considered.’ The reason is the difference in threat perception compared to that of Finland. ‘Geographically, Sweden is less vulnerable than its neighbour, which shares a 1,300-kilometre-long border with Russia.’ The Finnish population could easily relate to the videos and images emerging from Ukraine: ‘these could be our cities, bombed and destroyed’. Simply put, after the Cold War Sweden could, at least at the time, afford to cut back its military. There is also a political-cultural factor involved, Ries explains, which is that the ‘Swedes consider themselves a force for peace’: they have notably been active in many anti-nuclear and peace movement initiatives. Many felt that membership of a political-military alliance would undermine this noble goal. Others felt that joining NATO could well antagonize Russia and make Sweden a target in a war, whereas neutrality could keep Sweden safe. Ries ‘does not accept this kind of argument because Sweden and Finland are already considered targets by the Russian military, no matter what. At its core, NATO is essentially about deterrence, its aim is to prevent war. Finland and Sweden joining the Alliance only enhances the means to that objective.’ All in all, Russia launching a major war in Europe changed the calculus and provided an incentive for the Swedish government to apply for NATO membership, especially since its neighbour had already done that so quickly.

Tomas Ries is Senior Lecturer in Security and Strategy at the Swedish National Defence College in Stockholm. Photo Rickard Kilstrom

The Baltic Sea, a NATO lake?

Ratification of Sweden and Finland’s NATO membership is still in process, but what would the two countries contribute to the Alliance? What are the benefits for the new members as well as for the effectiveness of the Alliance as a whole? Both Sweden and Finland will join NATO ‘as contributors, not beggars’, Ries says. Each brings useful capabilities to NATO that will enhance the defensive power of an alliance aimed at preventing war.

As stated earlier, Finland has a significant ground force at its disposal. ‘They know how to fight Russia, if necessary’, according to Ries, ‘just like the Baltic states and Poland, but Finland has the numbers to make a difference’. On mobilisation Finland is able to field 280,000 trained and equipped soldiers, 60,000 in 7 manoeuvre brigades, backed up by 6 regional infantry brigades, 14 detached battalions and a host of local forces. It has a serious quantity and high quality of artillery (700 howitzers, 700 heavy mortars, 100 MLRS) and large stocks of ammunition. In Finland, national defence is built on a ‘foundation of the will of the people to defend the country’, Ries explains. Conscription is widely regarded as a useful and necessary contribution to the nation instead of as a burden. Therefore, he expects no changes in the conscription policy of Finland, meaning it will keep general conscription for men and voluntary service for women, whose numbers grow each year. In addition to a capable land force, Finland has a ‘modern, specialized navy, albeit small and lacking submarines. One of the navy’s strengths is mine warfare and countermeasures’, which is still in demand within NATO, especially in the Baltic Sea.

Sweden does have submarines, ‘a world class submarine force’ even, specialized in operations in shallow waters. The Swedish land forces are in need of rebuilding, however, after decades of cutbacks. Stockholm already started this process after the first Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014, with additional investments, partial reactivation of conscription of both men and women, and a significant budget increase, but with the current security situation this is taken even more seriously. Ries mentions that, unlike Finland, ‘Sweden has a retention problem with regard to junior officers’, although it is difficult to pinpoint its causes. On the other hand, the Swedish military is ‘top-heavy with colonels and generals’, Ries says, but this also presents an opportunity: ‘it would be relatively easy for Sweden to find personnel for NATO staffs and headquarters once it has joined the Alliance.’ The Finnish military ‘has always been very lean and might have trouble at first to contribute the required number of senior staff personnel to NATO. They will figure this out, however.’ Other assets that Sweden can provide are high-quality surface missiles and stealth corvettes, both of which are of great value in securing the Baltic Sea. ‘As a high-tech country, Sweden can contribute surveillance and sea and air patrol in the region.’ Lastly, Ries says, ‘Sweden provides a rear basing area in the Baltic region, which is very favourable to NATO.’

Figure 1 Military data of Finland and Sweden

In practical terms, a consolidated Nordic NATO membership could lead to interesting new opportunities for the Alliance. The Baltic states used to be a weak spot because of their small size and proximity to Russia proper and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, which is effectively a military fortress. It would be very challenging to reinforce the small Baltic states in wartime through a contested Baltic Sea. Ries states that recently ‘Finland has already announced plans to develop a capability, together with Estonia, to close the Gulf of Finland. The Russian Baltic fleet is based either at Kronstadt, at the inner end of the Gulf of Finland, or at Kaliningrad. If Finland and Estonia manage to put a credible A2/AD capability in place with anti-ship missiles, the Russian fleet would be locked in. In the event of a high-intensity war I expect Kaliningrad would also be destroyed as a military basing area within days. The Russian Baltic Fleet could then be bottled up very soon.’

Because of extensive preparations over the last two decades, Finland and Sweden can also rapidly plug into the NATO air operations system. Finland already operates 62 F/A-18 Hornets and is purchasing 64 US fifth generation F-35s. Sweden deploys its domestically produced fighter, the JAS Gripen, but it was proven in the past that its air forces can work together with NATO assets quite easily. For example, Ries states, ‘during the Libya intervention in 2011 Swedish aircraft seamlessly integrated with NATO air forces in terms of refuelling, communications, et cetera. They operated under certain political caveats but technically they were cooperating effectively.’ All in all, ‘with the Swedish and Finnish fighter jets, northern European NATO members have more than 200 four and fifth generation aircraft available: 145 Nordic F-35s (Norway 54, Denmark 27, Finland 64) and the 94 Swedish JAS Gripen, whose performance will be enhanced when integrated with F-35 capabilities. The UK and Poland can provide a boost with their 138 and 32 F-35s, respectively.’

Since 1992, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Sweden and Finland have made their armed forces interoperable with NATO, all but ensuring a smooth transition process once both countries formally join the Alliance. There might be one area of friction, however, when it comes to NATO’s regional command arrangements. Given Finland’s difficult experiences with and proximity to Russia, the country neither reduced its national defence forces nor its considerable expertise on Russia. Today, Finland thus fields what is probably the best qualified military in Europe when it comes to fighting Russia. Hence, Ries states, ‘there could be a justified reluctance in handing over command of Finnish forces and territory to non-Finnish authorities.’

Russia’s reaction: all bark but no bite?

After Sweden and Finland announced their intention to apply for NATO membership, Russia warned there would be consequences. What has Ries seen happening on that score? In fact, over the years, ‘Russia’s official policy regarding possible NATO enlargement in the Nordic countries has always been quite polite’, Ries says. ‘Moscow would say something like “If you join, we have to increase defensive measures”.’ Currently, however, Ries ‘has not seen any noticeable change. A usual Russian reaction would include demonstrations of force, like flights with heavy bombers, but those have largely been absent.’

Finnish and Swedish soldiers participate in a NATO exercise. Soon they will no longer be partners, but allies. Photo NATO

There might be some apprehension about cyber campaigns or information warfare targeting the prospective new NATO allies. ‘The media did report an increased number of cyber-attacks against Finland’, Ries says, ‘but the scope and kind of these attacks are still unknown, and they seem to have been thwarted.’ The same goes for influence operations. On the ground, the number of Russian troops in the vicinity of Finland have actually decreased. ‘Two fairly high-readiness brigades in northern Russia have been redeployed to Ukraine’, Ries explains, ‘it seems Russia is scraping the barrel for the Ukrainian war effort.’ So, until now, Russian threats directed at the two new NATO members have mostly been verbal. The reason is simple, says Ries: ‘With the war in Ukraine Russia has its hands full.’