How and to what extent did the Russian authorities use the Soviet-era concept of Reflexive Control against Ukraine? This article examines the theory of Reflexive Control and its role in Russian strategy.

Jelmar de Kievit*

Every war or conflict has its own characteristics and Russia’s recent conflicts are no exceptions. In 2014, to everyone’s surprise, ‘little green men’ suddenly appeared in Crimea and annexed the peninsula. Then, for eight years, Russian units fought intermittently in Ukraine’s Donbas region in support of separatists seeking affiliation with Russia while Putin continued to deny any involvement. According to experts, the fighting in the Donbas was a typical example of a frozen conflict between two independent states, in which there was a kind of stalemate between the parties for long periods of time while the fighting flared up from time to time increasing considerably in intensity. That the conflict was frozen did not mean that Russia was not preparing for full-scale war and, as Lawrence Freedman put it, ‘A state determined on war with another state would seek to maximise the military impact of the first move’.[1]

Russian paratroopers prepare for exercise Zapad-2021. Using the guise of operational training to prepare for combat operations is a classic Reflexive Control technique. Photo Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation

At first glance Russia’s war strategy in Ukraine in 2022 seemed to lack such an element capable of delivering a knockout blow to its adversary. How different that was from the almost bloodless annexation of Crimea in 2014, when the conquest of Ukrainian territory was over before most observers had even noticed. In articles in this journal and others the successes of the 2014 campaign are in part attributed to Russian military theory called Reflexive Control (RC). Three Dutch officers have published in recent years on the application of RC during the Russo-Georgian armed conflict in 2008 and during the earlier mentioned annexation of Crimea. In 2016 LtCol Tony Selhorst wrote an article for the Military Spectator on the use of this theory during the annexation of Crimea, followed by Major Christian Kamphuis in 2018 and Colonel Han Bouwmeester in 2021. This raises the question whether Russia’s military strategy for the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 also comprised the theory of Reflexive Control to maximise the military impact of the first move.

This article shows that Russia certainly had an extensive campaign plan in place at the outset of the war with Ukraine. A major part of that plan was based on the Soviet military theory of Reflexive Control to prepare and execute the invasion. It was designed to assist in quickly achieving the campaign’s objectives in support of the conventional military force deployed by the Russian authorities. This article consists of three parts; a short history and definition of RC, followed by a broad overview of Russia’s campaign plan in Ukraine and its RC uses, and finally the implications of Russia’s use of RC for the future and the West’s understanding of Russian warfare.[2]

Reflexive Control

Before an analysis of RC in the Russo-Ukraine war can be fully understood a short introduction to the theory is required. This part addresses the history of the theory, the mechanisms through which it is applied, its effects and the target audiences of the actions in which RC is applied. In a separate paragraph the role of the theory in modern Russian strategy is discussed.

In 1965, mathematician and psychologist Vladimir Lefebvre first came up with the term Reflexive Control. He developed a theory that could influence persons in such a way ‘that inclines them to make decisions predetermined by the controlling party’.[3] The potential of this theory for military strategy was recognized by the Red Army and Soviet intelligence agencies, whose officers started writing about it and further developed it for military application. In 1995, Major General M.D. Ionov redefined RC for the military as a method ‘to manipulate an opponent’s decision-making process in such a way that he voluntarily takes actions that lead to his own defeat.’[4] This can be done through all sorts of actions, both military and non-military, such as show of force, a feint, spreading disinformation, decoys or false-flag operations. In 1997, Colonel S.A. Komov compiled all these actions into eleven mechanisms through which Reflexive Control can be applied and he described the effects they were meant to have on an enemy.[5]

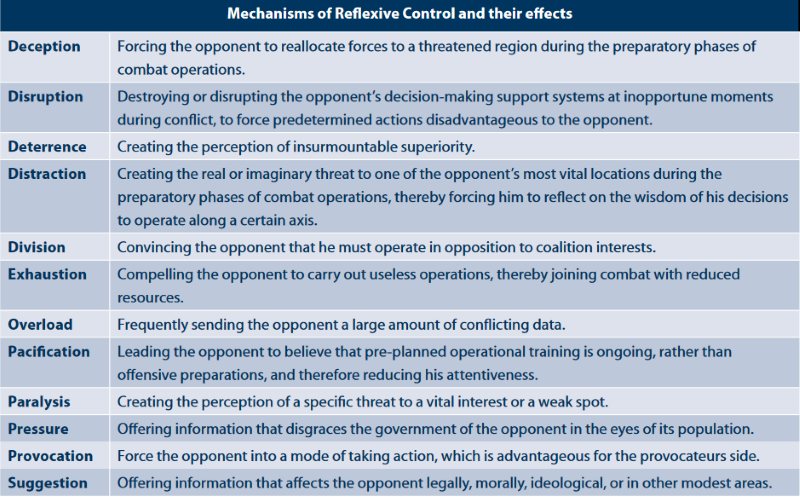

As the digital age was emerging in the nineties another Russian officer, Colonel S. Leonenko, also wrote about RC. With computers and the internet now also being used in the military, he argued that RC should also be applied against computers and what he called ‘technical reconnaissance assets.’[6] To account for RC against those digital systems a twelfth mechanism called ‘disruption’ has been added by the author of this article to the existing eleven described by Komov. The added twelfth mechanism of RC based on the remarks by Leonenko requires extra attention and therefore four examples from the Russo-Ukraine war are given in part two of this article to showcase the practical application of disruption. The effects of the eleven RC mechanisms together with disruption are summarized in Figure 1. Furthermore, it should be explained that the target audiences whose decision-making process is influenced can be subdivided into five types, namely 1. the population of the adversary, 2. the adversary’s political brass, 3. its military leadership, 4. its military forces, and 5. the international community supporting that adversary. As RC can be applied against Russia’s own population as well, this list also includes a domestic target audience.[7]

Figure 1 The twelve mechanisms of Reflexive Control based on Komov and Leonenko

Reflexive Control in modern Russian strategy

RC has gained renewed attention since Russia’s war against Georgia, the annexation of Crimea and the conflict in Syria. Observers from the West have described these activities as the application of RC operations to achieve effects against Russia’s opponents, both regionally and internationally, with varying degrees of success.[8] Moreover, two high-ranking Russian officers have given speeches hinting at the use of RC. Firstly, Chief of the Russian General Staff, Valery Gerasimov, de facto Russia’s chief military planner, while addressing a Russian military academy, said that in conflict non-military and military measures should be used in a ratio of four-to-one.[9] Timothy Thomas, an American expert on RC, noted that large parts of those non-military measures were used to achieve the mechanisms and effects from Figure 1.

Secondly, in 2015 at the same academy, Colonel General Andrey Kartapolov, at the time Director of Operations of the Russian General Staff, spoke about Russia’s New Type Warfare that closely resembled certain elements of RC.[10] His slides showed methods, such as putting pressure on the enemy, spreading division among the population, deceiving and distracting the enemy’s political and military leadership, and exhausting an adversary through cyber and special operations.[11] The contents of the speeches held by these high-ranking Russian officers, as well as the use of RC in past operations, indicate that the Russian authorities still rely on that theory to plan and execute military operations.

Reflexive Control in the Russo-Ukraine War

During his presidential campaign in 2019, Volodymyr Zelensky made the Ukrainian population two promises: 1. to end the frozen conflict in the Donbas, and 2. to halt the corruption plaguing Ukraine. Both promises were made to prepare Ukraine for joining NATO and the EU. Authorities in Russia were concerned about losing Ukraine from its sphere of influence, considering Ukraine as a buffer state against the Western world, and losing it was unacceptable to them. Therefore, Russia started planning a campaign that provided for regime change to bring Ukraine back into Russia’s sphere of influence. The following text describes Russia’s Reflexive Control activities in two time periods. The first is the ‘pre-war’ period, ranging from the start of 2021 up to the invasion; the second is the ‘war’ period, confined to the first month of the invasion. In this article, four different objectives were found, for which the Russian authorities used different mechanisms of RC. These objectives, called ‘Concentrations of Effort’ (COEs), were equally divided over the two periods. The four COEs are:

- Shaping the cognitive dimension of the Ukrainian population (pre-war);

- shaping the physical dimension of the Ukrainian military (pre-war);

- reducing combat effectiveness by disruption (war);

- limiting the conventional warfighting phase (war).

Each COE will be explained further in the following paragraphs, supported by a review of the corresponding RC actions.

COE 1: Shaping the cognitive dimension

The Russian authorities used the RC mechanisms of suggestion, division, deterrence and pressure in preparation of the invasion on 24 February 2022 to shape the cognitive dimension of Ukraine. The activities were directed at altering the individual and collective knowledge, perceptions and understanding of the situation.[12] They focussed on creating a welcoming attitude towards Russian troops and weakening support for the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF). The paragraphs below explain how the Russian authorities used the mechanisms of Reflexive Control to assist this first COE.

When Ukraine was invaded, the resistance by the UAF and local civilians showed that the hatred of the government did not exist: the RC ‘suggestion mechanism’ failed. Photo Teun Voeten

Suggestion: Throughout 2021 Russian state media targeted the Ukrainian population by spreading incorrect information about Zelensky and the government in Kyiv. Some of the observed narratives centred on Zelensky as being a Nazi, often referring to him with German slurs associated with the Second World War, or portraying him as a drug addict and a US puppet who came to power illegally. Another narrative that was spread claimed that Zelensky and his government planned the genocide of Russian minorities living in Ukraine.[13] To back up this claim, statements were added about chemical weapons provided by the US.[14] These four narratives were all spread between April 2021 and the start of the invasion in February the following year. Discrediting the political leadership of an opponent in this manner fits the suggestion mechanism of RC. The narratives aimed to create hatred of the government in Kyiv, especially in the south of Ukraine where the population is largely Russian-speaking. When Ukraine was eventually invaded, the resistance by the UAF and local civilians in Kherson and Mykolaiv showed that the hatred of the government did not exist and that a welcoming attitude towards Russian troops was not achieved, even in Southern Ukraine, by the suggestion mechanism. Ordinary citizens collectively dug trenches, built defences and monitored Russian troop movements to keep the invaders out.[15]

Division: To support the suggestion mechanism and bolster pro-Russian sentiment, in July 2021 Putin released an essay on the Kremlin website, in Russian and Ukrainian, entitled ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’. In the essay Putin reminded Ukrainians of their history as part of Russia and how they were ‘brotherly people’ sharing the same culture and language.[16] This essay attempted to sow doubt among Ukrainians about supporting the pro-Western course the country had taken. Moreover, it dissuaded ordinary Ukrainians from volunteering for the UAF or the Territorial Defence Forces. Thus, with the essay Putin and his inner circle tried to convince the population of Ukraine to act against their national interest of defending the country from invasion, which fits the division mechanism of Reflexive Control. However, it did not achieve its RC effect as the UAF was not lacking in volunteers; it even had to turn away citizens due to a shortage of weapons.[17]

Deterrence: On 14 January 2022, Ukraine’s government websites were defaced by a cyberattack accompanied by the warning ‘to be afraid and [to] wait for the worst’.[18] Again, this message targeted the Ukrainian population whose country was becoming increasingly surrounded by an estimated 190,000 Russian troops along its borders.[19] Faced with these odds and this ominous warning, for young Ukrainians volunteering for the Territorial Defence Forces or the UAF became an unappealing choice. Furthermore, the message targeted the UAF’s fielded military standing face-to-face with the Russian troops just across the border. For both targeted audiences the message was meant to weaken morale and resistance to a possible invasion by creating a sense of overpowering superiority, thus fitting the deterrence mechanism.

Pressure: Pressure is the final Reflexive Control mechanism used by the Russian authorities before the invasion to shape the cognitive dimension. Between 18 and 22 February 2022 the separatists in the Donbas spread footage of supposed attacks by the UAF on Russian minorities living there.[20] This supported the false narrative of genocide of Russian minorities already circulating in the months before portraying the UAF as an aggressor. With this footage, the separatists tried to justify an incursion by Russian forces under the pretext of peacekeeping in an attempt to weaken support for the government in Kyiv. Disgracing the government with these faked videos fits the pressure mechanism of Reflexive Control. That the goal of these actions was to portray Ukraine as the aggressor is supported by the statements on ‘protecting people facing humiliation and genocide by the Kiev regime’, made by Putin while announcing the Special Military Operation.

COE 2: Shaping the physical dimension

In addition to shaping the cognitive dimension, the Russian authorities also attempted to shape the battlefield by applying Reflexive Control against Ukraine’s military leadership during the preparation of the invasion. The intent of this second COE was to focus the military’s attention on the Donbas and thereby weaken defences in other areas, mainly around Kyiv. To achieve effects supporting this COE the mechanisms of pacification and distraction were used on multiple occasions.

Pacification: From April 2021 until the start of the invasion, Russia built up its troop strength around Ukraine in two phases. At the end of the first phase in April 2021 Russian Defence Minister Sergey Shoigu explained the build-up as military exercises and during the second phase a further build-up in November could be discovered. Again, the Russian authorities used the explanation for another exercise as a cover for their ongoing troop build-up.[21] While a return of the Russian troops to their home bases was announced, their equipment such as self-propelled artillery and armoured vehicles remained in theatre allowing for rapid deployment to the border if needed.[22] Using the guise of operational training to prepare for combat operations is a classic RC technique and Ukraine’s military leadership has repeatedly been the target of this mechanism. During the annexation of Crimea and other tensions between the countries since, it was Russia that held large troop exercises near Ukraine’s borders. Thus the scenario of a smaller incursion into Ukrainian territory by Russian troops, with the majority remaining on the Russian side of the border as a deterrent, moulded the minds of the UAF’s leadership. The most likely location for such a move would be the Donbas region and so the scenario of the annexation of that region emerged using the pacification mechanism.

Distraction: To emphasize the threat to the Donbas the Russian authorities used the distraction mechanism as well during two separate actions. The first is the already-discussed essay by Putin, in which he mentions the Donbas region six times. Moreover, he stated that Ukraine did not need the Donbas as it did not need Crimea.[23] Mentioning this link between the Donbas and the annexed Crimea further supported the created scenario, thus focusing the UAF’s leadership on the Donbas.

As the threat of war was growing at the start of 2022, Russian amphibious warships moved from the Baltic Sea towards the Black Sea. These ships were observed moving through the English Channel, the Strait of Gibraltar and the Bosporus and they clearly showed signs of carrying a large quantity of sailors, soldiers and materiel. Some experts concluded that it would have made more military sense to move the amphibious troops over land to Crimea and embark them there more covertly.[24] On the other hand, overtly and intentionally moving these prepared warships through NATO-controlled waters was obviously intended as a distraction. The Russian authorities knew that NATO partners would share the intelligence about the ships with the Ukrainian military leadership, for whom the movement of these ships only further supported the scenario of an incursion into the South-East of Ukraine, now also from the sea. In this way, the Russian authorities attempted to use two RC mechanisms to shape the battlefield before the invasion. It is interesting to note that these mechanisms seem to have had a beneficial effect for the Russian authorities. As Ukraine’s best units were stationed near the Donbas, it became known that Russian troops outnumbered their opponents in the Kyiv region by twelve to one.[25]

COE 3: Reducing combat effectiveness by disruption

While Putin announced the start of Russia’s Special Military Operation against Ukraine to ‘demilitarize’ and ‘de-Nazify’ the country, Russian troops were moving across the border. Meanwhile, hacker groups, long affiliated with Russia’s military security service known as the GRU, had already penetrated Ukrainian cyberspace carrying out two cyber-attacks, one aimed at Ukrainian military communications and another at their computer systems. The two attacks will be discussed below, in addition to two other actions by the Russian authorities which applied RC to support this third COE.

A Ukrainian soldier installs a Starlink internet terminal. Access to the Starlink satellite network mitigated the effects of Russia’s attack against Ukrainian satellite communications. Photo Support Forces of Ukraine Command

The Viasat attack: During the opening minutes of the invasion, hackers attacked the ground station of the KA-SAT satellite owned by the American company Viasat, disrupting internet connections throughout Ukraine.[26] More importantly, this satellite was also in use by the UAF for their military communications, which were now severely hampered. A senior official of the Ukrainian State Services of Special Communication and Information Protection later commented on the interruption saying that it was ‘a really huge loss in communications at the very beginning of the war.’[27] By attacking the satellite the Russian authorities achieved a disruptive effect, which prevented the UAF from communicating and sharing up-to-date battlefield intelligence. This in turn forced Ukraine’s fielded military to take actions based on incomplete information and without proper coordination against the invading Russian forces. However, the effects of this attack were mitigated by Elon Musk providing Ukraine with his Starlink satellite network within two days.[28]

The HermeticWiper attack: The second cyberattack is known as ‘HermeticWiper’ or ‘FoxBlade’, depending on which internet security company’s reports were reviewed. This attack used data-destroying malware, which infected Ukrainian government computer systems using Microsoft Windows and rendered them inoperable.[29] Among the government agencies operating Microsoft Windows was Ukraine’s Ministry of Defence, including the UAF. This disruption is disastrous enough when coming under attack from another state but the implications went further than just the inability to access the computers. Complicated cyber-attacks take a lot of time to prepare and often hackers intrude into targeted systems through backdoors, or hidden digital access points, long before the actual attack happens. Therefore, the UAF had to assume that the data about their plans, positions and strength on those computers were also accessible to the attackers and were therefore known to Russian intelligence. This forced the military leadership to adopt an ‘ad hoc’ strategy, which is more challenging than a pre-planned strategy. In doing so-the Russian authorities achieved an RC effect by using the disruption mechanism against the computer systems of the Ukrainian military.

Decoys and jamming: The two other ways used by the Russian authorities to achieve the disruption effect of RC were by deploying aerial decoys and using Electronic Warfare (EW) systems. Russian EW systems jammed Ukrainian air defences in the initial phase of the invasion to such an extent that the Ukrainian Air Force was forced to assume full air defence duties during the first days of the war.[30] Committing the Ukrainian Air Force to this task was highly disadvantageous for the UAF, since the Russian Air Force (VKS) already outmatched its opponent in quality and quantity, at least on paper. It meant fewer threats from the ground to the VKS, less close-air support for UAF ground troops and overall more strain on the Ukrainian Air Force. The effect of the disruption is illustrated by a quote from a Ukrainian lieutenant, saying: ‘How can you contain their offensive when we have no air defence?’.[31]

In addition, the Russian military deployed aerial decoys over Ukrainian airspace to draw fire from still-operational air defences. While compelling these systems to engage decoys, thus wasting ammunition, is the exhaustion mechanism of Reflexive Control, it had a second effect as well. The disruption caused by the decoys to the Ukrainian computer systems trying to detect enemy aircraft led to those air defences exposing themselves to the VKS. This is exactly what the Russian authorities had planned for as the VKS flew up to 140 sorties per day in the first days of the war to strike these still functioning air defences.[32]

COE 4: Limiting the conventional warfighting phase

The fourth COE was to limit the timespan Russian forces would need to engage in conventional warfighting against the UAF. The Russian authorities attempted to achieve this through RC’s division, deterrence, provocation and pressure mechanisms. A silent but gruesome witness to the conviction among Russian planners that RC would achieve this COE is a bloodied OMON-trooper vest, found in Bucha.[33] OMON is a riot-police unit, part of Russia’s National Guard, the so-called Rossguardia, which was meant to suppress riots in Kyiv after it had been captured. OMON’s presence among front-line military units goes to show that the Russian authorities did not expect the resistance their troops were encountering. Moreover, the logistical failure of the poorly defended Russian column nearing Kyiv after a week of fighting unveils the lack of preparation for a full-scale conventional war against their adversary.[34]

The next few paragraphs explain the RC mechanisms used by the Russian authorities and how they supported the COE which should have resulted in a walk-over for Russian forces.

Division: In the final days of February 2022, Russian authorities tempted the UAF leadership in three separate actions to overthrow the government in Kyiv or at least not resist the invading forces. Putin made a personal appeal to the UAF in a video broadcast, while Russian generals contacted their Ukrainian counterparts directly and ‘bot farms’ spread the message via text to lower-ranking Ukrainian officers.[35] The behaviour the Russian authorities hoped to provoke with these messages was to incite the overthrow of the government in Kyiv by the military, also known as a coup d’état. Trying to convince an opponent that he must operate in opposition to coalition interests fits the division mechanism of RC. Moreover, this action nurtured distrust among Ukrainian officers. The possibility that some officers might have accepted Russian deals potentially created suspicion and affected decision-making by slowing it down or by altering the choices made. However, resilience and cohesion within the UAF actually mitigated the effects of such efforts by the Russian authorities.[36]

Division was also spread across the UAF’s fielded military through deceiving statements by Russian state media. After the Snake Island incident Russian news outlet TASS reported that the garrison there surrendered and that together with other Ukrainian forces who had given up they would be returned to their families after disarmament.[37] The Russian authorities made it seem that surrendering to Russia was an acceptable option as they were of the opinion that Ukrainian soldiers facing an overwhelming opponent would surrender more easily if there were no negative consequences of such an action for them. Therefore, this message was meant to spread division amongst the UAF and reduce its will to fight. It is also interesting to note that the Ukrainian government might have tried to counteract these statements by falsely stating that all troops stationed on Snake Island had heroically perished while defying Russia, setting an example for other Ukrainian troops.[38]

Deterrence: On 28 February TASS again spread incorrect information about the conflict by stating that the VKS had achieved air superiority in Ukrainian airspace, while this was actually not the case. However, sending this message served another purpose. After the initial loss of internet communications in Ukraine, the country regained normal internet access on 27 February, according to internet monitoring organisation NetBlocks.[39] This meant that the claim of air superiority could be spread among Ukrainian troops through social media platform Telegram, which was and still is at the heart of the propaganda battle, according to Ian Garner, an expert on Russian propaganda.[40] In short, the Russian authorities tried to demoralize Ukrainian troops by creating the sense that Russia had a far superior military force and that without sufficient air support Ukraine’s fight would be over. Demoralizing, and forcing the surrender of, the UAF would remove the need to defeat them on the battlefield and so assist the mentioned COE.

Through destruction in Mariupol, the Russian military tried to entice Ukraine’s political and military leaders into yielding other surrounded cities. Photo Wanderer777

Provocation: Throughout March 2022, Russian forces systematically destroyed the southern city of Mariupol. Although this seems to fit Russian military doctrine on urban warfare, looking at the state Russian forces left Grozny and Aleppo in,[41] it also sent a clear message to Ukraine’s political and military leadership. After Ukraine rejected the ultimatum to surrender the city to Russian forces, the destruction continued, reducing the city to rubble. Through this action, the Russian military tried to entice Ukraine’s political and military leaders into yielding other surrounded cities, thus preventing the destruction of what they were trying to protect. Forcing an opponent to voluntarily take action advantageous to the controller like this fits the provocation mechanism of RC. It can be concluded that the Russian authorities attempted to avoid costly urban warfare and protracted sieges of other cities, thus supporting the fourth COE. It is interesting to note that in June the major city of Sievierodonetsk was almost surrounded by Russian forces and also given an ultimatum.[42] Again, Ukrainian authorities rejected the demand to surrender, although a week later UAF troops were ordered to withdraw,[43] showing the possible effect the provocation mechanism had on the Ukrainian authorities’ decision-making.

Pressure: The final action used the pressure mechanism of RC to support the COE. It attempted to get Ukrainians to surrender by spreading utterly faked footage of Zelensky surrendering to Russia. The video appeared on the website of Ukraine 24 TV, while a written message that Zelensky had fled Kyiv was displayed on the Ukraine 24 TV channel’s news ticker.[44] Hackers had infiltrated these systems and used them to spread false information that disgraced Zelensky in the eyes of the Ukrainian population and military, thus fitting the pressure mechanism of RC. The purpose was to incite Ukrainian forces to surrender, had it not been for the poor quality of the deep fake and the debunking video by Zelensky himself, released almost immediately after the incident.

Conclusions and implications

It is clear that just as with the 2014 annexation of Crimea the Russian authorities have used the theory of RC to plan and execute the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The nine mechanisms of RC observed as having been used prior to and during the first months of the 2022 war in Ukraine were suggestion, division, deterrence, pressure, pacification, distraction, disruption, exhaustion and provocation. However, whereas in 2014 RC had been very successful, in 2022 it mostly failed to produce the effects of the four ‘Concentrations of Efforts’ (COEs) discussed above which were aimed at maximising the impact of Russia’s first move. Ukrainians did not welcome Russian troops as liberators and were very determined to stand their ground, which turned out to be a failure on Russia’s part in shaping the cognitive dimension of the Ukrainian population. Although Ukraine’s best military units were stationed near the Donbas due to the shaping of the physical dimension, they still managed to mount the adequate defence of Kyiv and in the North-Eastern part of Ukraine. At the very start of the conflict combat effectiveness was reduced due to the disruption caused by COE 3. However, the failure to actually destroy all Ukrainian air defences and Elon Musk providing the UAF with his Starlink internet network mitigated the effects of this COE. Finally, Ukrainian troops, inspired by their brave president, stood firm in the face of adversity, not allowing incorrect or unconfirmed information to demoralize them. Therefore, Russian troops were forced to defeat them on the battlefield, despite all the actions focussed on limiting the need for an extended period of warfighting or COE 4.

There is a possibility that, on the one hand, the success of RC during the annexation of Crimea convinced the Russian authorities of the use of RC for the campaign plan in 2022 but that, on the other, Ukrainians were more alert to manipulation and influencing operations by Russian authorities. Consequently, the failure of RC in this campaign does not mean that the theory as a whole should be dismissed. It is plausible to assume that Russian authorities will try to learn from their mistakes and adjust the application of RC. Their actions will become more sophisticated and more dangerous to the targets they will be trying to manipulate and control. Therefore, as war becomes increasingly dependent on computers and other technical systems such as radars, the addition of the ‘disruption’ mechanism to RC theory is essential to detect and counteract the appliance of RC by Russia in the future.

* Jelmar de Kievit is a Second Lieutenant of the Netherlands Marine Corps.

[1] Lawrence Freedman, The Future of War: A History (Penguin Books, 2017) 66.

[2] This article is based on a military art bachelor thesis written at the Netherlands Defence Academy.

[3] Vladimir Lefebvre, Lectures on the Reflexive Games Theory (New York, Macmillan Publishers, 2010) 82.

[4] Timothy Thomas, ‘Russia’s Reflexive Control Theory and the Military’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 17 (2004) (2) 242. See: https://doi.org/10.1080/13518040490450529.

[5] Sergei Komov, ‘About Methods and Forms Conducting Information Warfare’, Voennaya Mysl (Military Thought) (1997) 18-22; Thomas, ‘Russia’s Reflexive Control’, 247-249.

[6] Thomas, ‘Russia’s Reflexive Control’, 247.

[7] Keir Giles, James Sherr, and Anthony Seaboyer, ‘Russian Reflexive Control’, ResearchGate (Defence Research and Development Canada, October 2018) 7. See: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328562833_Russian_Reflexive_Control.

[8] Han Bouwmeester, ‘The Art of Deception Revisited (Part 2): The Unexpected Annexation of Crimea in 2014’, Militaire Spectator 190 (2021) (10) 498–507. See: https://www.militairespectator.nl/sites/default/files/teksten/bestanden/militaire_spectator_10_2021_bouwmeester.pdf; Frederick Kagan and Kimberly Kagan, ‘Putin Ushsers in a New Era of Global Geopolitics’, Institute for the Study of War, September 28, 2015, 5. See: https://www.aei.org/articles/putin-ushers-in-a-new-era-of-global-geopolitics/.

[9] Dmitry Adamsky, ‘Cross-Domain Coercion: The Current Russian Art of Strategy’, Institut Français Des Relations Internationales, November 2015, 23.

[10] Ronald Sprang, ‘Russian Operational Art, New Type Warfare, and Reflexive Control’, Small Wars Journal, April 9, 2018. See: https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/russian-operational-art-new-type-warfare-and-reflexive-control.

[11] Timothy Thomas, ‘The Evolving Nature of Russia’s Way of War’, Military Review July-August 2017 (2017) 37.

[12] Peter Pijpers and Paul Ducheine, ‘Influence Operations in Cyberspace – How They Really Work’, University of Amsterdam Digital Academic Repository (UvA, September 24, 2020) 5. See: https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/55821459/20210201_Pijpers_Ducheine_Influence_operations_in_cyberspace.pdf.

[13] RIA Novosti, ‘В Раде заявили о подготовке Зеленского к ‘резне русских’ (Rada says Zelensky preparing to ’massacre Russians’)’, February 13, 2022 (translated through DeepL.com). See: https://ria.ru/20220213/reznya-1772524724.html.

[14] Ian Smith, ‘The Disinformation War: The Falsehoods about the Ukraine Invasion and How to Stop Them Spreading’, Euronews, March 8, 2022.

[15] By Abdujalil Abdurasulov, ‘Ukraine War: How Russia Took the South - and Then Got Stuck’, BBC News, February 27, 2023. See: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-64718740.

[16] Vladimir Putin, ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’, July 12, 2021. See: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181.

[17] Tyler O’Neil, ‘Ukraine Military Turns Volunteers Away as 140k Ukrainians Come Home to Fight Russia’, Fox News, March 7, 2022.

[18] Katharina Krebs, ‘Cyberattack Hits Ukraine Government Websites’, CNN, January 14, 2022. See: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/01/14/europe/ukraine-cyber-attack-government-intl/index.html.

[19] David Brown, ‘Ukraine Conflict: Where Are Russia’s Troops?’, BBC News, February 23, 2022. See: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-60158694.

[20] Bellingcat Investigation Team, ‘Documenting and Debunking Dubious Footage from Ukraine’s Frontlines’, Bellingcat, February 23, 2022.

[21] BBC News, ‘Russia to Pull Troops Back from near Ukraine’, April 22, 2021; Alexander Marrow, ‘In Russia-Ukraine Faceoff, Both Sides Stage Combat Drills’, Reuters, November 25, 2021.

[22] Zahra Ullah, Anna Chernova, and Eliza Mackintosh, ‘Russia Pulls Back Troops after Massive Buildup near Ukraine Border’, CNN, April 23, 2021. See: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/04/22/europe/russia-military-ukraine-border-exercises-intl/index.html.

[23] Putin, ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’.

[24] John Barranco et al., ‘Will Russia Make a Military Move against Ukraine? Follow These Clues’, Atlantic Council, January 20, 2022.

[25] Isobel Koshiw and Dan Sabbagh, ‘The Battle for Kyiv Revisited: The Litany of Mistakes That Cost Russia a Quick Win’, The Guardian, December 28, 2022.

[26] Matt Burgess, ‘Viasat Satellite Hack Spills Beyond Russia–Ukraine War’, WIRED, March 23, 2022. See: https://www.wired.com/story/viasat-internet-hack-ukraine-russia/.

[27] Burgess, ‘Viasat Satellite Hack’.

[28] BBC News, ‘Elon Musk’s Starlink Arrives in Ukraine but What Next?’, March 1, 2022. See: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-60561162.

[29] Brad Smith, ‘Digital Technology and the War in Ukraine’, Microsoft on the Issues, February 28, 2022. See: https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2022/02/28/ukraine-russia-digital-war-cyberattacks/.

[30] Justin Bronk, Nick Reynold, and Jack Watling, ‘The Russian Air War and Ukrainian Requirements for Air Defence’, Royal United Services Institute Journal, November 7, 2022, 7. See: https://static.rusi.org/SR-Russian-Air-War-Ukraine-web- final.pdf.

[31] Abdurasulov, ‘Ukraine War: How Russia Took the South - and Then Got Stuck’.

[32] Bronk, Reynold, and Watling, ‘The Russian Air War’.

[33] Carl Schreck, ‘“Sent As Cannon Fodder”: Locals Confront Russian Governor Over “Deceived” Soldiers In Ukraine’, RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, March 6, 2022. See: https://www.rferl.org/a/russian-soldiers-ukraine-cannon-fodder-governor/31739187.html.

[34] Jack Watling, Oleksandr Danylyuk, and Nick Reynolds, ‘Preliminary Lessons from Russia’s Unconventional Operations During the Russo- Ukrainian War, February 2022–February 2023’, RUSI, March 29, 2023, 4. See: https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/preliminary-lessons-russias-unconventional-operations-during-russo-ukrainian-war-february-2022.

[35] Mykhaylo Zabrodskyi et al., ‘Preliminary Lessons in Conventional Warfighting from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: February– July 2022’, Royal United Services Institute, November 30, 2022, 25; Julie Coleman, ‘Russian Operatives Sent 5,000 Text Messages in a Failed Attempt to Incite Ukrainians to Attack Their Own Capitol’, Business Insider, April 1, 2022.

[36] Kalev Stoicescu et al., ‘How Russia Went to War: The Kremlin’s Preparations for Its Aggression Against Ukraine’, International Center for Defence and Security, April 25, 2023, 20. See: https://icds.ee/en/how-russia-went-to-war-the-kremlins-preparations-for-its-aggression-against-ukraine/.

[37] TASS, ‘Ukrainian Garrison at Snake Island Surrenders to Russian Armed Forces’, February 25, 2022. See: https://tass.com/politics/1410761.

[38] Tim Lister and Josh Pennington, ‘Audio Emerges Appearing to Be of Ukrainian Fighters Defending Island from Russian Warship’, CNN, February 25, 2022. See: https://edition.cnn.com/europe/live-news/ukraine-russia-news-02-24-22-intl/h_2e17e59214679efefede60d5fb481432.

[39] James Pearson and Raphael Satter, ‘Internet in Ukraine Disrupted as Russian Troops Advance’, Reuters, February 27, 2022. See: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/internet-ukraine-disrupted-russian-troops-advance-2022-02-26/.

[40] Vera Bergengruen, ‘How Telegram Became the Digital Battlefield in the Russia-Ukraine War’, Time, March 21, 2022. See: https://time.com/6158437/telegram-russia-ukraine-information-war/ .

[41] Brian Glyn Williams, ‘Grozny and Aleppo: A Look at the Historical Parallels’, The National, November 24, 2016.

See: https://www.thenationalnews.com/arts/grozny-and-aleppo-a-look-at-the-historical-parallels-1.211868.

[42] Pjotr Sauer, ‘Ukraine Ignores Russian Ultimatum to Surrender Sievierodonetsk’, The Guardian, June 15, 2022. See: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jun/15/ukraine-ignores-russian-ultimatum-to-surrender-sievierodonetsk.

[43] Peter Beaumont and Pjotr Sauer, ‘Last Ukrainian Forces in Sievierodonetsk Ordered to Withdraw’, The Guardian, June 24, 2022.

[44] Digital Forensic Research Lab and Roman Osadchuk, ‘Russian War Report: Hacked News Program and Deepfake Video Spread False Zelenskyy Claims’, Atlantic Council, March 16, 2022. See: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new- atlanticist/russian-war-report-hacked-news-program-and-deepfake-video-spread-false-zelenskyy-claims/.