Naval blockades, maritime interdiction, embargo or inspection operations are elements in a wide spectrum of naval instruments for deterrence and other coercive diplomacy strategies. How can these types of operations contribute to effective deterrence and coercion strategies? Various success factors determine the outcome of the blockade and still, the success of a coercive diplomacy campaign is only partly a result of an effective blockade. This article examines the success factors, looking at literature and two historical use cases: the Third Taiwan Strait crisis of 1996 and the food-for-oil embargo targeting Saddam Hussein’s Iraq between 1991 and 2003. From these cases, it seems that an effective blockade depends, among other factors, on freedom to act, suitability of the region, international support and the willingness for the duration of the operation. It needs to integrate seamlessly in an overall coercive campaign to make that campaign successful as a whole.

The blockade of Athens’ harbour Piraeus by the Spartans, following the defeat of Athens in the Sea Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC may well be the first recorded naval blockade in history.[1] After the loss of their fleet at Aegospotami, the Athenians retreated behind their city walls. The Spartans, led by admiral Lysander, besieged the city and blockaded its harbour depriving the city of food supplies. After a winter of famine, Athens had to surrender. Ever since, blockades have been widely recognized as an indispensable part of naval warfare. Today, we see Russia use naval blockade tactics in the Black Sea, threatening and attacking ships sailing from and to Ukrainian ports.[2] Both Sparta and Russia use naval blockades during an actual war. This article, however, focuses on contemporary use of naval blockades and related maritime operations below the threshold of war; in deterrence and coercive diplomacy. What exactly are blockades and how are they used in coercive diplomacy? What factors support or limit the effectiveness of blockades? How do blockades fit into strategies of coercion?

‘Oh, this old thing? She’s nothing really. You should see the real heat I’m packing back home.’ President Theodore Roosevelt depicted as defending the United States’ commercial interests in Latin America from the European powers, published in Judge Magazine, New York, 1904. Image Harvard University, Louis Dalrymple

The research question this article addresses is therefore the following: ‘To what extent are naval blockades effective in Coercive Diplomacy?’ The research question is addressed by first discussing definitions and legal, military and political contexts in paragraph two and subsequently success factors of those types of blockades in paragraph three. Then, in paragraph four, I will look into some relevant and contemporary use cases to validate these success factors, before concluding with recommendations for the use of naval blockades in coercive diplomacy.

Blockades and other maritime coercive measures – legal, military and political contexts

The term ‘naval blockade’ is used inconsistently throughout literature and in policy making.[3] Its common and most widely used description is captured in the San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea,[4] and found its way to, among others, the US ‘Commander’s handbook on the law of naval operations’.[5] This handbook uses the following definition: ‘Blockade is a belligerent operation to prevent vessels and/or aircraft of all States, enemy and neutral, from entering or exiting specified ports, airfields, or coastal areas belonging to, occupied by, or under the control of an enemy State.’

Two observations have to be made now. First, the definition and use of ‘blockade’ is predominantly used in the ‘jus in bello’ context, i.e. the law governing armed conflicts. This means that in legal terms a naval blockade is considered an act of war. This observation is relevant in a coercion and deterrence context, since issuing a blockade might signal an unwanted step upwards on a given escalation ladder for a conflict at hand. It is for this reason that the United States used the term ‘naval quarantine’ instead of ‘blockade’ during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.[6]

A U.S. Navy Lockheed SP-2H Neptune flying over a Soviet freighter in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962. the United States used the term ‘naval quarantine’ instead of ‘blockade’ during the Cuban Missile crisis to avoid unwanted escalation. Photo U.S. Navy

The second observation that can be made from this definition is that a blockade targets all vessels and aircraft in a given area. It is a typical denial operation, requiring sea control; it requires freedom of action for one’s own military forces and supporting units.

The naval blockade, following its definition, is therefore a rather blunt instrument that may be ill-suited in conflicts below the threshold of war, in great power competition and other situations that ask for more refined and flexible coercion and deterrence measures.

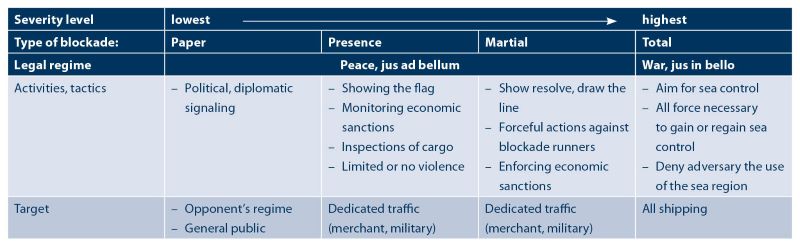

Building on naval warfare theory, Adam Biggs et al propose a useful conceptual framework that refines and supplements this traditional total naval blockade approach.[7] They argue that the beforementioned wartime ‘blockade’ represents one end of a severity spectrum. Other, less severe forms of blockade complete that spectrum in times of peace. These forms differ on either the geographic location, the implications for neutral parties, the use of force or the handling of blockade runners. In their article, Biggs et al introduce the ‘enforcement model’ that allows for a more detailed approach to blockades and their enforcement. In this model, the least severe implementation of a naval blockade is the Paper blockade, that essentially is no blockade since it only contains the declaration of a blockade without any accompanying actions by the coercer – it merely fulfils a political or diplomatic role. The first actual blockade type then is the Presence blockade, where a naval force shows its determination to the cause by being present in a given sea area, showing the flag, possibly checking cargoes and manifests and apply minimal force upon blockade runners. A severity level higher is the Martial Blockade that allows for forceful intervention against certain vessels (for example, determined by types of cargo, flag state, intent, destination etcetera). The final and most severe implementation is the traditional Total Blockade, as defined above. The enforcement model is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1 Blockade types, based on the enforcement model of Biggs et al

Peacetime blockades[8] pose some challenges with regard to legitimacy of the use of violence: who authorizes the level of force needed for a Presence or Martial Blockade and what is the legal regime under which the operation is considered lawful? International legitimacy for the use of force can be obtained by resolutions of the UN Security Council, but that may not be feasible, especially in the current great power competition. International treaties, such as the Proliferation Security Act[9] or the SUA 2005,[10] may provide legitimacy for semi-forceful acts as boarding, inspecting and subsequent holding of vessels, but use of force can always be considered an act of war against either the flag state or a coastal state. Signalling peaceful intent whilst threatening with the use of force is a very delicate balance, especially when this force is used against presumably neutral parties, e.g. merchant vessels. To address this issue, Ivan Luke of the US Naval War College proposes a framework for the array of ‘naval activities (…), according to the source and nature of the authority for action.’[11] These regimes of authority range from consent actions (e.g. permissive extraction of non-combatants) via law enforcement and UN tasks to ultimately national defence and war.

A final remark has to be made with regard to the use of Rules of Engagement (ROEs) during naval blockades of any kind. During the Cuban Missile crisis, it became clear that the maritime interception operation, or ‘quarantine’ called for very detailed ROEs to obtain the strategic goal of compelling Russian cargo ships not to proceed to Cuba, whilst not escalating the conflict to nuclear war.[12] Also, Luke mentions ROEs in his framework,[13] albeit only in relation to UN operations. I would argue, together with J. Ashley Roach, that the Rules of Engagement are a useful instrument to guide actions within a naval blockade. Roach states that ROE’s ‘should be designed to allow military courses of action that advance political intentions with a minimum chance for undesired escalation or reaction.’[14]

To conclude, naval blockades vary in enforcement level, legal basis and are complex, use different labels in different contexts and rely on clear ROEs to serve both the coercive intent as well as the legal regime for the particular legal and political context. With that remark, we are now entering the discussion on the success factors for the use of naval blockades in coercive diplomacy.

Key naval blockade success factors for coercive diplomacy

Having this understanding of the types of blockades with their respective legal regimes, military consequences and political contexts, allows us to focus on the success factors for this instrument in coercion and deterrence contexts. Following Schelling, the term coercion is used here as the overarching term describing both deterrence (preventing the adversary to act) and compellence (force the adversary to act in a desired way).[15] As Peter Jakobsen argued, coercion policies are expected to fail unless a policy is implemented that contains four elements: a credible threat, a compliance deadline, an assurance against future demands and a possible reward when complying with the demands.[16] Of course, unambiguous demands communicated clearly to the adversary preludes these elements. Additionally, Jakobsen puts forward that two additional conditions apply to obtain successful coercive diplomacy: the adversary prefers to comply with the demands rather than to lose a war, and the opponent acts rationally and is free from misperceptions.[17] The key element in Jakobsen’s ideal policy is the credible threat of force. Here is where the naval blockade success factors come into play; it is obvious that this credible threat needs to be perceived by the opponent when it is confronted with the naval blockade activities. It is essential that the term ‘perceived’ is used here, since coercion is a process of conveying perceptions.[18]

Standing NATO Maritime Group 2 transits the Mediterranean. Naval blockades in general are successful when they convey the message of credible threat. Photo U.S. Navy, Crayton Agnew

So, naval blockades in general are successful when they convey the message of credible threat. The blockade should influence the ‘coercion calculus’[19] in such a way that the adversary gives in to demands. Typically, a coercer’s policy never consists of a naval blockade exclusively, but probably a broader portfolio of whole-of-government coercive policies, including economic, diplomatic and informational policies. All of these policies should integrate well, and add up to the beforementioned ‘credible threat’. It should be noted here that naval blockades are suited for both ‘narrow’ as well as ‘broad’ deterrence or coercion policies:[20] the Total Blockade aiming at the military superiority at sea, or sea control, denying the adversary the use of the sea for military purposes is an example of ‘narrow’ coercion or deterrence, whilst the naval blockade types in a lower severity setting can be used in a ‘broad’ coercion or deterrence policy, for example by the enforcement of economic sanctions.

Biggs et al describe a set of key factors that contribute to the effectiveness of naval blockades.[21] Other authors have contributed to this set, such as Bruce Elleman[22] and Ivan Luke who looked at the role of legal regimes throughout the naval blockade spectrum.[23] Below, a summarized set is given.[24]

Freedom of action. In a broad sense, naval blockades are effective if the coercer exercising the blockade has the military superiority or the international legitimacy, a UNSCR mandate for example, that allows it to freely conduct the operations at, above or under the sea. Ideally, both elements are present.

Suitable naval assets. Naval blockades can be performed by a diverse set of assets ranging from sea mines to surface ships, aerial support by planes and drones, and submarines. Depending on the blockade’s goal and enforcement policy, a type of asset is operationally suitable, but also plays a role in the perception of the coerced opponent and the public at large. For example, using sea mines is a suitable asset for total blockades but this typically does not contribute to the public support because of their covert and indiscriminate nature.

Regional suitability. Naval blockades need to be planned in a suitable region, that allows for conduct of operations desired by the coercer, meanwhile preventing the opponent to use land or air to break the blockade. Also, the proximity of the region to the coercer (preferably close) and to the opponent is relevant. A blockade may well be positioned at distant locations from the opponent, aiming at relevant global trade routes.[25]

International cooperation and support. This factor relates both to the coercer as well as the opponent. The target of coercion should not be able to seek relevant international support to break the blockade or successfully question its legitimacy. The coercer on his turn ideally has international support for its blockade operations. A blockade, mandated by a UNSC Resolution is an undisputed source of international support, but international cooperation and support can consist of coalitions or regional alliances.[26]

Sustainable. The coercer needs to sustain the blockade for an uncertain amount of time, with resources being consumed and units rotated. An important factor in the sustainability is the will-power of the coercer,[27] especially if this is a coalition of states that might have different views on duration, costs and domestic support for the blockade. Also, the coerced opponent might use information warfare or influence campaigns to erode the will-power of the coercer and consequently end or relieve the blockade.

Self-sufficiency of the target. When a blockade targets the economy of the opponent, the self-sufficiency of that opponent becomes important – how long can it sustain without resources under embargo, enforced by the blockade?

Feasible. The types of blockade that call for the enforcement of targeted sanctions need to be designed in a way that allows the coercer to tactically execute on it. Cargo, especially containers, on board merchant vessels heading for the opponents’ harbours are heterogenous in ownership, and that ownership may even be transferred between owners while underway.[28] This cargo must be inspected meticulously for contraband that falls under the targeted sanction regime. Adding to the complexity of the inspection task is the involvement of neutral flag states and commercial ship’s owners.

Knowing these success factors, it is interesting to look at a set of typical use cases and validate the contribution of these factors and see if the blockades were indeed effective. Also, even if the blockade itself was effective considering the abovementioned factors, the question remains whether the overall coercive diplomacy in that case was successful and if that is in some way related to the naval blockade. In a review of a potential oil blockade of China by the US, Gabriel Collins points out that naval blockades and the resulting effect on strategic level coercion needs careful consideration and hardly constitutes a causal relationship.[29] As another consideration, Fiona Cunningham puts forward that blockades may serve as a useful additional rung in the escalation ladder.[30]

Relevant and contemporary use cases

The most prominent use case for naval blockades in coercive diplomacy is of course the blockade of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. An abundance of academic literature and popular magazines, books and movies cover this case, so I will focus here on two lesser-known cases.[31] In their book Naval Blockades and Sea Power, Bruce Elleman and Sarah Paine describe these cases among sixteen others including an extensive analysis.[32] For this article, the below cases are chosen since they contain two different types of naval blockades, namely a Presence Blockade (Iraq) and a Martial Blockade (Taiwan); they are situated in separate regions with different actors and different strategic goals, which allows for a comparative case study on a least-similar basis, within the limitations of this article. Both cases are described first, and then checked against the success factors described before and evaluate whether or not this was an effective blockade. Finally, the evaluation is made if the blockade contributed to the overall coercive diplomacy effort.

A Russian oil tanker stands under Omani naval escort after being diverted by the U.S. Navy on suspicion of busting UN sanctions on Iraq (2000). Photo ANP, AFP, Mohammed Mahjoub

‘Third Taiwan Strait Crisis’ - China versus Taiwan, 1996

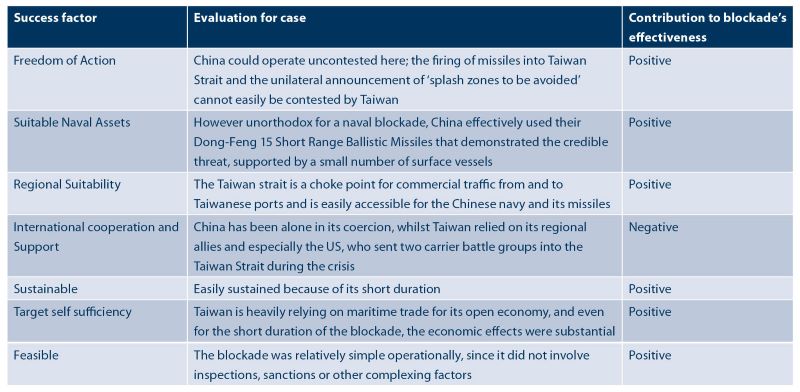

During 1996, with origins in late 1995, China started an influence and coercion campaign in the months preceding parliamentary and presidential elections in Taiwan.[33] China’s aim was to show its force and consequently influence the Taiwanese electorate to support parties that favour a more conciliatory position towards China. Part of China’s campaign was a series of missile tests and naval exercises for which it announced publicly that missile splash zones were to be avoided during these tests, lasting around 8 to 15 March. This is effectively a blockade of these zones, severely impacting the Sea Lines of Communication around Taiwan and this had a large effect on merchant traffic. It either avoided Taiwan or had to choose longer, significantly more expensive routes into Taiwanese’s main ports. The blockade ended after the presidential elections.[34] Table 2 checks this case against the beforementioned success factors.

Table 2 Evaluation of success factors for case China versus Taiwan, 1996

From this table, it is reasonable to say that the blockade was effective. The blockade led to severe economic impact in the opponent, Taiwan, whilst posing little cost for the coercer, China. However, Fisher and Rahman consider this case a strategic coercive failure since the initial objective – influencing the elections in Taiwan – did not materialize well enough and the side effects involved investments in countermeasures by Taiwan and its allies Japan and the US.[35] Elleman argues that this might be a too strict view; the coercion has had deterrent effects, since it may have prevented Taiwan from declaring its independence.[36] It is fair to say that China did not design its coercion policy following Jakobsen’s ideas, lacking both a reward and an assurance. The blockade was effective tactically, but could not compensate for design flaws in China’s overall coercion policy.

Iraq food-for-oil embargo, 1990-2003

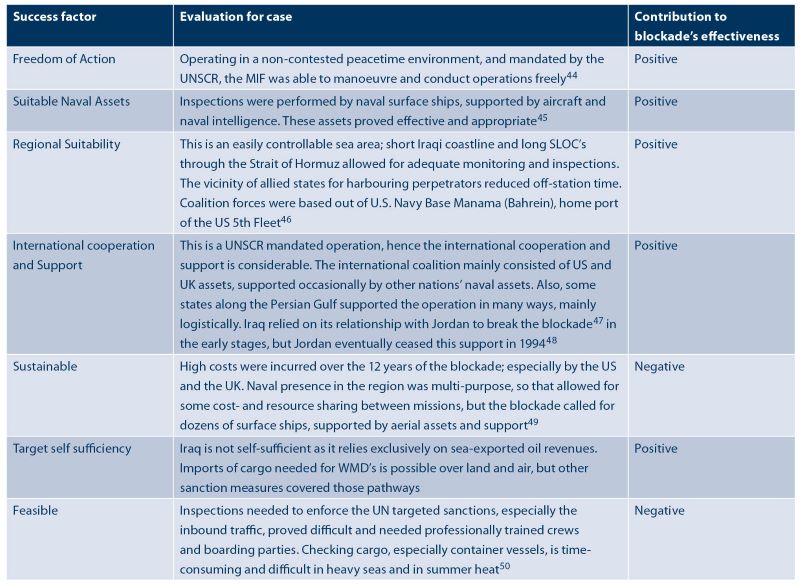

During the 1990’s, an international coalition force[37] led by the US conducted a naval blockade to enforce economic sanctions on Iraq, publicly known as the ‘food-for-oil’ embargo that allowed Iraq to export a capped amount of oil and to purchase food, medicine and other essentials for Iraq’s population.[38] Executing on several UN Security Council resolutions,[39] the coalition forces inspected vessels entering or leaving Iraqi ports with respect to their conformity to these resolutions and, in case of a violation, were allowed to escort ships to nearby designated ports, such as Kuwait City. The goal of this blockade was to support the UN in compelling Iraq to comply with the UN demand of discontinuing its pursue of achieving weapons of mass destruction as called for in UN Security Council Resolution 687.[40] During a period of twelve years, the Maritime Interception Force (MIF) inspected traffic to that avail. This blockade ended with the 2003 invasion that toppled the Iraqi regime. The blockade in this case is a ‘presence blockade’ with limited rules for enforcement by military force but showing the resolve of the global community to the cause captured in UNSCR 687. Table 3 evaluates the effectiveness of this blockade.

Table 3 Validation of blockade effectiveness for the Iraqi food-for-oil case

Despite the duration costs and complexity of the operation, this blockade can be labelled as effective, also because the MIF inspections showed resolve of the coalition and consequently discouraged potential perpetrators of the blockade worldwide.[41]

The support of this effective blockade to the overall success of the coercive diplomacy is inconclusive; James Godrick argues that the blockade prevented Iraq from constructing weapons of mass destruction[42] and consequently was a success, but other scholars such as Risa Brooks argue that the sanctions as an instrument of coercion did not achieve the coercive goal, and even enriched Iraqi leadership individually.[43] Also, the international community continued to accuse Iraq of obtaining or developing these weapons, despite the blockade, by land-based smuggling and the refusal of independent inspections by the international community. Eventually, the sanction regime did not compel the Iraqi regime to comply with international demands and this refusal ultimately led to the 2003 invasion.

Russia’s blockade of the Black Sea

Currently, the Russian navy tries to blockade traffic from and to Ukrainian ports. Since 19 July 2023, after Russia’s withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative, its Ministry of Defence issued a warning that ‘all vessels sailing in the waters of the Black Sea to Ukrainian ports will be regarded as potential carriers of military cargo’.[44] Using the key success factors discussed before, it is interesting to look at the effectiveness of this blockade. Since the blockade is ongoing, its ultimate effectiveness is yet to be determined, but several factors can be observed.

The blockade is part of the overall war effort against Ukraine. It aims at depleting Ukraine from vital imports and exports such as grain to sustain its economy, and by targeting all vessels, regardless of cargo or flag state it can be seen as a ‘total blockade’ in the Enforcement Model 0(see Table 1). From what is available from public sources, the blockade scores ‘high’ on Regional Suitability, Feasibility and Target self-sufficiency: the Ukrainian coastline is short and its proximity to the main base of the Russian Black Sea fleet allows for easy rotation and short transit times. Over the course of the conflict, the score on Suitable naval assets decreased significantly: the Russian Black Sea fleet was, at least on paper, a large and effective naval force able to exercise sea control necessary for this blockade type. However, since the loss of the cruiser Moskva in April 2022, sea control is lost by the Russian navy, severely hampering its capability to exercise controlled total blockades. Only by using denial assets such as sea mines, Russia can aim to blockade or influence shipping.[45] Also, it seems to score ‘low’ on the factors of Freedom of action and International Cooperation & Support. Mainly as a consequence of successful attacks by Ukraine on naval assets and installations, the Russian Black Sea fleet cannot exercise sea control to a level that is necessary for a total blockade.[46] Additionally, Russia cannot rely on relevant international support and enforce the blockade using allies or international diplomatic pressure. And as a consequence of this, the blockade has been broken repeatedly and consistently.[47]

A poster-size stamp in central Kyiv depicting a Russian warship sunk after Ukrainian attacks in the Black Sea. Since the loss of the cruiser Moskva in April 2022, sea control in the Black Sea is lost by the Russian Navy. Photo SOPA Images/Shutterstock, Oleksii Chumachenko

Furthermore, the sustainability of the blockade has faded since Ukrainian attacks have forced the Russian navy to withdraw eastward, away from the Crimean peninsula.[48] This leads to the preliminary conclusion that Russia’s blockade is not effective and it seems that Russia’s strategic goal of closing down Ukrainian imports and exports is farther away than in the beginning of the war. However, if Russia would be able to obtain freedom of action in the future by regaining sea control in the Black Sea, a blockade of Ukrainian ports is still possible and its consequences can impact the Ukrainian economy significantly.

Conclusion

In the previous paragraphs, I have analyzed the usefulness of naval blockades as an instrument for coercive diplomacy policies. Blockades can be deployed in several levels of severity, from mild presence blockades to wartime total blockades. Besides severity, blockades can also be used in narrow and broad deterrence or coercion strategies.

Several success factors have been identified. They are freedom of action, suitability of assets and the region, the level of international support for both the coercer and the opponent, the sustainability of the blockade, the opponent’s ability for self-sufficiency whilst under blockade and the tactical and technical feasibility of the chosen type of blockade. Validating these success factors against two use cases showed that an effective blockade can contribute to the strategic coercive goals. The sanctions and the subsequent blockade against Iraq severely limited its capability to develop weapons of mass destruction and contributed to the resolve of the international community to its cause. China used unorthodox means of blockading Taiwan, using the threat of land-based missiles, but did so effectively, although the overall success of the coercive campaign may have been greater if China had provided a ‘carrot’ – incentives and reassurances – in addition to the ‘stick’ of the blockade.

It seems promising to validate strategic effectiveness of naval blockades in more contemporary use cases. For now, it is likely that success in coercive diplomacy lies in ‘checking all boxes’ proposed by leading coercive and deterrence theorists. Naval blockades definitely have a role but cannot compensate for strategic flaws in the design and execution of the whole coercive campaign.

[1] John R. Hale, Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy (Penguin, 2009) 242-3.

[2] Raul Pedrozo, ‘Russia-Ukraine War at Sea: Naval Blockades, Visit and Search, and Targeting War-Sustaining Objects’, Article of War blog, Lieber Institute, 25 August 2023.

[3] B.A. Elleman and S.C. Paine, Naval Blockades and Seapower - Strategies and Counter-strategies, 1805-2005 (London & New York, Routledge 2006) 4.

[4] International Institute of International Humanitarian Law, San Remo Manual on International Law applicable to Armed Conflict at Sea. See: https://iihl.org/naval-warfare/. Section IV Methods of warfare, 93-108.

[5] U.S. Navy Department, The Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations (Washington, D.C., Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M, 2007).

[6] U.S. Navy Department, The Commander’s handbook on law of Naval Operations, section 4.4.8: ‘Maritime Quarantine’.

[7] Traditionally, blockades were divided according to the proximity model, where ‘close blockade’ meant a near-shore blockade, preventing enemy warships to either enter or leave their harbour and ‘distant’ blockades, with less tight control by the blockading party over a larger sea area. See A. Biggs, D. Xu, J. Roaf, and T. Olson, ‘Theories of Naval Blockades and their application in the twenty-first century’, Naval War College Review 74 (2021) (1) 2-31.

[8] Sometimes referred to as ‘maritime interdiction’ or ‘maritime interception’ operations in literature or policy documents.

[9] The 2003 Proliferation Security Initiative is an international treaty aimed at stopping the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and has been ratified by 105 nations (2020). See: https://www.state.gov/proliferation-security-initiative/.

[10] Protocol of 2005 to the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation, abbreviated as ‘SUA 2005’. See: https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/SUA-Treaties.aspx.

[11] Ivan T. Luke, ‘Naval Operations in Peacetime: not just “Warfare Lite”’, Naval War College Review 66 (2013) (2) 17.

[12] Jeffrey Barlow, ‘The Cuban Missile Crisis’, in: B. Elleman and S.C.M. Paine (eds.), Naval Blockades and Sea power: Strategies and Counter-Strategies, 1805-2005 (Routledge, 2006) 164.

[13] Luke, ‘Naval Operations in Peacetime’, 19.

[14] J.A. Roach, ‘Rules of Engagement’, Naval War College Review 36 (1983) (1) 49.

[15] Thomas C. Shelling, Arms and Influence (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1966) 72-73.

[16] Peter Viggo Jakobsen, Western Use of Coercive Diplomacy after the Cold War (St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1998) 144.

[17] Jakobsen, Western Use of Coercive Diplomacy, 33

[18] Michael J. Mazarr, ‘Understanding Deterrence’, in: F. Osinga and T. Sweijs (eds.): Deterrence in the 21st Century—Insights from Theory and Practice (T.M.C. Asser Press, 2021) 21.

[19] Coercion calculus is the – rational – process where the cost of resistance is weighed against the benefits of compliance. See Mazarr, ‘Understanding Deterrence’.

[20] Ibidem, 18.

[21] Biggs et al, ‘Theories of Naval Blockades and their application’, 18-25.

[22] Elleman & Paine, Naval Blockades and Sea power, 263.

[23] Luke, ‘Naval Operations in Peacetime’, 19.

[24] The factors mentioned are conceptually conflated from the sets proposed by Elleman, Biggs and Luke, and cover all factors although sometimes rewritten for analytical purposes in this article.

[25] Fiona Cunningham and David Collins give some insight in the role of proximity of the geographic disposition of coercer, opponent and the sea area that needs to be controlled, blocked, or inspected. See F.S. Cunningham, ‘The Maritime Rung on the Escalation Ladder: Naval Blockades in a US-China Conflict’, Security Studies 29 (2020) (4) 730-768 and G. Collins, ‘Maritime Oil Blockade Against China—Tactically Tempting but Strategically Flawed’, Naval War College Review 71 (2018) (2) 49-78.

[26] For example, during the Cuba Crisis, the US sought support for its quarantine of Cuba by the Organization of American Nations. UN Support was not achievable because of the veto right of the Soviet Union.

[27] Jakobsen, Western Use of Coercive Diplomacy, 42-43. Jakobsen mentions several factors and variables that produce ‘will-producing patterns’.

[28] Cunningham, ‘The Maritime Rung on the Escalation Ladder’, 747.

[29] Collins, ‘Maritime Oil Blockade Against China, 73: ‘An oil blockade is not itself a strategy; rather, it is an action appropriately subsumed into a larger economic, diplomatic, and military campaign. It is also an action that in physical, trade-warfare terms would be akin to a nuclear strike on the global economy.’

[31] The Cuban Missile Crisis case is an example of a seemingly effective blockade, followed by a desired strategic outcome from the US standpoint – the ‘coercer’ in this crisis. An excellent description of this case can be found in the book High Noon in the Cold War by Max Frankel (2004).

[32] Elleman and Paine, Naval Blockades and Seapower.

[33] Also known as the ‘Third Taiwan Strait Crisis’, see Chris Rahman, ‘Ballistic Missiles in China’s Anti-Taiwan Blockade Strategy’, in: Elleman and Paine, Naval Blockades and Seapower, 215-223.

[35] Richard Fisher, ‘China’s Missiles over the Taiwan Strait’, in: Lilley & Downs, Crisis in the Taiwan Strait (NDU Press, Washington, D.C., 1997) 175-180; Rahman, ‘Ballistic Missiles in China’s Anti-Taiwan Blockade Strategy’, 220-221.

[36] Elleman and Paine, Naval Blockades and Seapower, 252.

[37] The author participated in this MIO as naval officer on board of the Dutch frigate HNLMS Van Galen in March 1997.

[38] The actual wording of this category in the UN SC Resolution is ‘finance the purchase of foodstuffs, medicines and materials and supplies for essential civilian needs’.

[39] UNSCR 661 (1991) initiated the MIO embargo, this was concluded by UNSCR Resolution 1153, February 1998.

[40] UNSCR 687 (1991) that built on the earlier resolution 661 issued a few days after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990. See: https://www.un.org/depts/unmovic/documents/687.pdf; UNSCR 661.

[41] James Goldrick, ‘Maritime sanctions enforcement against Iraq, 1990-2003’, in: Elleman and Paine, Naval Blockades and Seapower, 213.

[42] Goldrick, ‘Maritime sanctions enforcement against Iraq’, 213.

[43] Risa A. Brooks, ‘Sanctions and Regime Type, What Works, and When?’, Security Studies 11 (2010) (4) 39.

[44] Howard Altman, ‘Cargo Ship Enters Danube Despite Russia’s Black Sea Shipping Threat’, The War Zone weblog, 1 august 2023. See: https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/cargo-ship-enters-danube-despite-russias-black-sea-shipping-threat.

[45] Henk Warnar, ‘Ukraine and Russia in the Black Sea: a naval war of mutual denial’, Atlantisch Perspectief 47 (2023) (4).

[46] Nicole Wolkov, Daniel Mealie, and Kateryna Stepanenko, ‘Ukrainian Strikes Have Changed Russian Naval Operations in the Black Sea’, Institute for the Study of War, 16 December 2023. See: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-strikes-have-changed-russian-naval-operations-black-sea.

[47] Altman, ‘Cargo Ship Enters Danube Despite Russia’s Black Sea Shipping Threat’.

[48] Thomas Grove, Jared Malsin, ‘Russia Withdraws Black Sea Fleet Vessels From Crimea Base After Ukrainian Attacks’, Wall Street Journal, 4 October 2023. See: https://www.wsj.com/world/russia-withdraws-black-sea-fleet-vessels-from-crimea-base-after-ukrainian-attacks-51d6d4f5.