The development of parallel warfare – based on the ability to strike simultaneously throughout the battlespace – characterizes the evolution of armed conflict in the past five decades. Initially, this ability was limited to superpowers or large alliances that had access to prohibitively expensive high-tech weapon systems. However, during the last decade, this ability has become available to small states, none-state actors and even small groups of individuals who creatively weaponized cheap and commercially available technology. Consequently, anything can now be targeted by anyone at all times. This increases the importance of an art that is somewhat neglected in Western military thought: the art of not being a target. This article explores the schools of thought concerning the ways to master and apply this art in contemporary and future conflicts.

Targets are central in the Western view on warfare. This view aims to avoid annihilation and attrition by adopting a manoeuvrist approach. As NATO states, ‘The manoeuvrist approach seeks to shape understanding, avoid strengths and selectively target and exploit critical vulnerabilities and other points of influence to disrupt cohesion and to seize, maintain and exploit the initiative. Such an approach offers the prospect of achieving rapid gains or results that are disproportionately greater than the resources applied.’[1] However, is this approach always applicable? Do all belligerents have critical vulnerabilities or other points of influence? This article holds that this is not the case: Increasingly, belligerents make the strategic choice not to be targets.

To substantiate this thesis and to understand this evolution, the article first explains the difference between sequential and parallel warfare. Next, the article defines what a target is in parallel warfare. It then builds on this analysis and this definition to explore the schools of thought concerning the art of not being a target. Finally, the article concludes with the implications of the art of not being a target on operational planning.

Sequential warfare as the obvious character of armed conflict

Without being able to know for sure, the wish to live in peace is probably as old as mankind itself. Of course, life has always been a struggle for survival. However, in this evolutionary struggle, one of the main advantages of humans over other species has been the ability to communicate and to cooperate. Moreover, what is the use of fighting between humans as long as no storable food surplus exists or as long as wealth cannot be captured in transportable goods like gold? The ancient Greek historian Thucydides concisely captures this situation in the preface of his book on the Peloponnesian War: ‘Greece was not originally a country of stable settlements... Each group grazed its own land for subsistence, not building up reserves or farming the land, as it was never known when someone else might attack and take it from them.’[2] To avoid being targeted, people did not acquire anything they could not afford to lose.

However, the antithesis is equally true. As soon as groups of people created food surpluses and transportable wealth, they became targets to those who wanted to take them by force. To avoid attack, these groups needed to be strong, fortified and allied. Consequently, to reach the food surpluses and transportable wealth, the attacker first had to overcome the obstacles that stood between him and the defender: alliances, fortifications, and armed forces. And this has been the case for centuries.

Belligerents apply strategy to deal with this situation. Strategy consists of the rational linkage between ends, ways and means. Because the means are always limited, ways must be found to use the means against well-chosen weaknesses: divisions within alliances, low or thin sections of fortification walls or armed forces marching in columns rather than positioned in battle formations. The aspect of choice is reflected in the definition of the word ‘target’. According to Merriam-Webster, a target is ‘something or someone fired at or marked for attack’.[3] This definition gives much credit to the attacker. It is the attacker who decides what a target is by firing at it or by marking it for attack. The definition made sense as long as warfare was sequential. During such a war, campaigns consisted of events that were sequentially arrayed in space and time.

Sequential warfare starts from the assumption that a defender will position forces and obstacles between the attacker and what he wants to protect. For centuries, this assumption was a basic fact because it was impossible for forces to leave the earth’s surface and show up somewhere unexpectedly in great strength. In his classic study on war, Clausewitz envisioned the essence of war as a clash between the opposing sides’ main forces. Central in his thought is the notion of centre of gravity: ‘The blow from which the broadest and most favorable repercussions can be expected will be aimed against that area where the greatest concentration of enemy troops can be found; the larger the force with which the blow is struck, the surer its effect will be. This rather obvious sequence leads us to an analogy that will illustrate it more clearly—that is, the nature and effect of a centre of gravity.’[4] These reasonings led to the ideal of the decisive battle: a single confrontation of massed forces that decides and ends the war. The textbook example took place during the Austro-Prussian War. As Samuel Newland writes, in ‘a seven weeks war, Prussian troops went into motion on 15 June 1866, and the decisive battle—Königgrätz—was fought on 3 July.’[5] The Prussian commander Helmuth von Moltke destroyed the Austrian troops and threatened Vienna. As a result, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck could impose Prussia’s political will on Austria.

The advent of parallel warfare

All this changed with the development of military capabilities that can create stand-off destructive effects throughout the battlespace. The crux of the matter is that nowadays, anything can be targeted everywhere and at all times, regardless of what is placed between the owner of what is desired and the adversary who desires it. Warfare has become parallel. Several theorists have analyzed this new situation. Two of them are well known: John Warden and John Boyd. Their focus is on the innovative use of modern military technology. Their plea is to avoid using advanced military technology to improve classical military strategies – as developed by theorists such as Clausewitz – and to develop completely new strategies.

The Austro-Prussian war was sequential by necessity. Von Moltke could not threaten Vienna without marching his army towards it. Consequently, he had to defeat the Austrian army that blocked his way. John Warden and John Boyd realized that technologically advanced forces did not face similar constraints. Stand-off weapon systems offered other strategic options. In a similar strategic setting, these weapon systems could destroy the Austrian forces from the air or interdict their supply lines. However, John Warden had other ideas: ‘All of our thinking on war is based on serial effects, on ebb and flow. The capability to execute parallel war, however, makes that thinking obsolete.’[6] To clarify this point he explains that ‘As strategists and operational artists, we must rid ourselves of the idea that the central feature of war is the clash of military forces.’[7] Warden modeled the enemy as a system of five concentric rings with the leadership in the middle and the fielded armed forces in the fifth, outer ring. The three other rings are the organic essentials, infrastructure, and the population. Central to his thesis is the assumption that ‘there is an increase in numbers of people or facilities moving from the center to the fourth ring (one or two leaders, a few dozen organic essentials, many infrastructure facilities and a large number of people).’[8] Therefore, Warden’s approach focuses on attacks on the two inner rings: ‘States have a small number of vital targets at the strategic level… These targets tend to be small, very expensive, have few backups, and are hard to repair. If a significant percentage is struck in parallel, the damage becomes insuperable.’[9]

Operation Allied Force marked the first time in military history that a campaign came to a successful conclusion with air power alone. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Like Warden, Boyd holds that the best way to win is to target enemy command systems. Contrary to Warden, Boyd does not focus on the physical destruction of the targets themselves, but on the impediment of the communication and cooperation between them. In his view, an attacker must 'Operate inside adversary's observation, orientation, decision, action [OODA] loops to enmesh adversary in a world of uncertainty, doubt, mistrust, confusion, disorder, fear, panic and chaos.’[10] The result is the loss of cohesion and therefore, the reduction of the adversary to ‘many non-cooperative centres of gravity.’[11]

A good example of parallel warfare is NATO’s Operation Allied Force against Serbia to end the oppression of the ethnic Albanian population in Kosovo in 1999. NATO defined clear objectives for the operation and stated that these objectives would be achieved by air strikes only.[12] To paraphrase Warden, NATO ridded themselves of the idea that the central feature of war is the clash of military forces. There were good reasons for that. About a third of all Serbian forces occupied Kosovo. A 1998 NATO analysis of the size of the land forces required to defeat the Serbian army in Kosovo had called for a massive intervention of about 60,000 soldiers.[13] The price was simply too high. The air strikes started on 24 March 1999 and after 78 days President Slobodan Milosevic of Serbia yielded to NATO demands. For the first time in military history, a campaign came to a successful conclusion with air power alone. NATO had not used land forces at all. Moreover, the Serbian forces did not play much of a role either. The campaign organized targets in groups. According to Anthony Cordesman, ‘Only 25 percent of these target groups were Serbian military. Another 15 percent were air defense. Most of the remaining 60 percent were factories, infrastructure, oil and POL facilities, roads, bridges, railroads, and command and control facilities.’[14] In other words, most air strikes were aimed at the two inner rings of Warden’s model. NATO’s approach was consistent with Warden’s assertion that ‘The most critical ring is the command ring because it is the enemy command structure... which is the only element of the enemy that can make concessions.’[15]

It did not occur to Boyd that operating inside the adversary’s OODA loop might reduce the adversary to many cooperative centres of gravity. Nor did Warden seriously consider the possibility that the enemy could continue to function as a system despite the destruction of the command ring. A rare event in the 19th century and several recent armed conflicts prove both Boyd and Warden wrong.

What is a target?

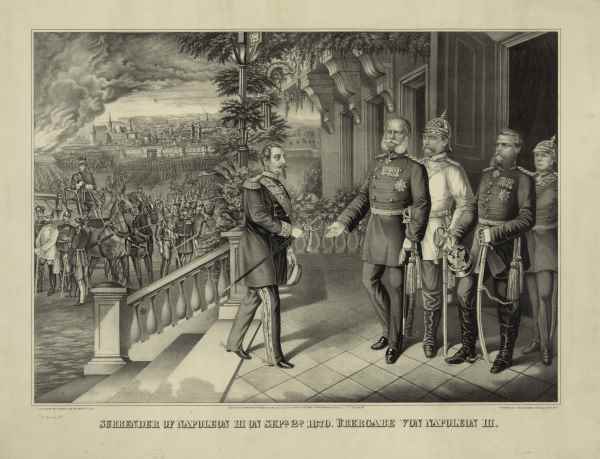

History offers a rare example of parallel warfare in the 19th century: the Battle of Sedan on 1 September 1870 during the Franco-Prussian war. It was parallel warfare by coincidence because the French Emperor, Napoleon III, decided to accompany his troops. This means that during the battle, Warden’s inner ring (the leadership) and outer ring (the French armed forces) were in the same place and so was Boyd’s OODA loop. During the battle, the French forces suffered 20,000 casualties. The remaining 100,000 soldiers were captured. Among the prisoners of war was the Emperor himself. According to all aforementioned theorists, the battle of Sedan should have ended the war. Prussia had struck a decisive blow to Clausewitz’ centre of gravity. They had captured Warden’s inner ring: the Emperor, the only element of the enemy that can make concessions. And they had reduced the adversary to Boyd’s many non-cooperative centers of gravity. Yet, the war did not end there. Within days, the French created a new inner and outer ring. As soon as 4 September 1870, crowds of citizens stormed the parliament and proclaimed the republic.[16] Also, as Geoffrey Wawro says, there quickly emerged ‘a new class of soldier called the franc-tireur, a French deserter or civilian who took up arms to obstruct the German advance.’[17] The franc-tireurs conducted hit-and-run attacks in parallel throughout the battlespace. To win the war, the Prussians had to find something to force the French to the negotiating table. They decided to lay siege to Paris and bombard it with heavy artillery. Unable to cope with this level of destruction, the French surrendered in January 1871. This means that the real decisive target was not the French army or the Emperor, it was Paris. This means that – in parallel warfare – a target is anything that the adversary cannot afford to lose.

After the capture of Napoleon III (left) by King Wilhelm in the Bellevue Castle at Sedan on 2 September 1870 the Franco-Prussian war went on, which proved theorists like Clausewitz, Warden and Boyd wrong. Photo Library of Congress

Love

The Battle of Sedan proved that Clausewitz, Warden, and Boyd can be wrong. To his credit, Warden mentions this possibility in his article: ‘The utility of the five-ring model may be somewhat diminished in circumstances where an entire people rises up to conduct a defensive battle against an invader... When people do fight to the last, they are fighting as individuals and in essence each person becomes a strategic entity unto himself. While such may be possible for the defense, it is not for the offense. It is a special case (emphasis added).’[18] But is this true? Increasingly, individuals unite successfully to resist invading or occupying forces. When societies defend themselves with Warden’s fourth ring (the population), they create ‘too many targets,’[19] and therefore no targets at all. The Prussian commander – von Moltke – understood the danger of creating hatred among the invaded population. In a speech to parliament, he stated: ‘What we have won with arms in hand in half a year, we must protect with arms for half a century, so that it is not snatched away from us again. Since our happy wars we have won respect everywhere but love nowhere. (emphasis added)”[20] That a battle-hardened Prussian considers love a necessity to achieve decisive victory should inspire us to take a closer look at strategies that exploit this lack of love.

Mastering the art of not being a target

For those who are defenceless, all wars are parallel. The enemy can attack at will. The attacker has no walls to breach or phalanx to outflank. For centuries, being defenceless was a fact of life for many people because, according to Thucydides, ‘The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.[21] The first theorist who developed a successful strategy to win against a stronger opponent was Mao Tse-tung. To him, being defenceless was a choice: ‘There is in guerrilla warfare no such thing as a decisive battle; there is nothing comparable to the fixed passive defense that characterizes orthodox war. In guerilla warfare, the transformation of a moving situation into a positional defensive situation never arises.’[22] The main prerequisite for success in guerrilla warfare is von Moltke’s ‘love’, or what Brigadier General Samuel Griffith calls ‘sympathetic support’. According to him ‘Historical experience suggests that there is very little hope of destroying a revolutionary guerrilla movement after it has survived the first phase and has acquired the sympathetic support of a significant segment of the population.’[23] In these circumstances, the guerillas can operate without being a target by observing four basic rules: ‘When guerrillas engage a stronger enemy, they withdraw when he advances; harass him when he stops; strike him when he is weary; pursue him when he withdraws.’[24] However, the consequences of the first rule are far reaching. The choice to be defenceless means that there is no upper limit to the distance of the withdrawal from the advancing enemy. When in 1933 the Chinese Nationalists attacked in force, the Communists decided to shift their base to Shensi Province, which meant marching almost 6,000 miles.[25] Such a move was only possible in the vast expanse of the Chinese countryside. That means that Mao’s strategy is not applicable in regions where such manoeuver room does not exist. A conceptual solution to this problem was proposed by an Egyptian theorist called Sayid Qutb.

Qutb was the ideologue of the Muslim Brotherhood, a movement created in Egypt to resist colonial rule. It later spread to other Middle Eastern countries. The Brotherhood continued to exist after independence and in Egypt – as in other Muslim countries – it is the most important form of organized opposition against ruling autocrats. The movement’s original aim was to return society to ‘true Islam’ to counter Christian and Western colonial influences. The main effort was preaching because according to Hasan al-Bannah, the movement’s founder, ‘when the people have been Islamized, a truly Muslim nation will naturally evolve.’[26] To generate popular support the movement provides services to those in need. Its success, writes Gilles Klepel, ‘stems from its capacity to unite, around their program, various social groups, by waging a campaign of proselytism, accompanied by an intense charitable activity, centered around dispensaries, workshops, and schools, installed in the periphery of mosques.”[27] Because their activities are centered around mosques, the branches of the movement are by definition tied to fixed localities. They could therefore not withdraw when they were attacked. Consequently, the movement did not engage in militant activities themselves. For that, they relied on another organization called The Free Officers led by Gamal Abdel Nasser. The Free Officers ended British control over Egypt with a military coup in September 1952. This rise to power ‘increased the expectations of the Muslim Brotherhood. They thought that the Nasserites would be the secular wing of their own organization.’[28] However, soon after, Islamic organizations were suppressed. ‘Nasser saw the Brotherhood as composed of power seekers who were using religion for their own purposes, says Özlem Tür Kavli.[29] Increasingly, the Brotherhood started to oppose Nasser and ‘the assassination attempt on Nasser in 1954 provided the regime with the excuse to crush the movement.’[30] Qutb and other key figures of the Muslim Brotherhood were imprisoned. As Kavli writes, ‘Ironically, the policy of purging Brotherhood members from the system and sending them to camps in the desert strengthened the movement.’[31] The prisoners were considered martyrs. Also, ‘members that were sent into exile in the rich Gulf states formed economic networks that would finance their Islamic movement after the death of Nasser.’[32]

Despite its military presence in Iraq the US missed the rise to prominence of Muqtada al-Sadr within the Shi’a community. Photo U.S. Army, Russell Klika

On the ideological side, Qutb wrote his most influential book – Milestones – while in prison. It is a complete and coherent view on the way to achieve his ideal of an Islamic State. It includes an elaborate justification of the use of violence to achieve that objective. ‘Islam has the right to take initiative. Islam is not a heritage of any particular race of country; this is God’s religion, and it is for the whole world. It has the right to destroy all obstacles in the form of institutions and traditions to release human beings from their poisonous influences, which distort human nature and which curtail human freedom,’ Qutb wrote.[33] After seeing how Nasser cracked down on the Brotherhood, Qutb understood that to succeed in creating an Islamic State, the Brotherhood not only needed popular support, but also the capability to fight. The years in prison convinced him that the colonial powers were not the only enemy. According to Ladan Boroumand and Roya Boroumand, ‘He identified his own society (in his case, contemporary Muslim polities) as among the enemies that a virtuous, ideologically self-conscious, vanguard minority would have to fight by any means necessary, including violent revolution, so that a new and perfectly just society might arise.’[34] The central problem then became the creation of the armed vanguard while avoiding it being detected and targeted by those in power. Soon after the publication of Milestones, Qutb was hanged, but his book inspired many Islamist movements that combine charitable activities and the provision of essential services with organized violence. Among them are Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Sadr II Movement in Iraq.

Islamist movements are remarkably apt at emerging without being noticed and targeted. In 1985, Yitzak Rabin—then Israeli Defence Minister—observed that, ‘among the many surprises, and most of them not for the good, that came out of the war in Lebanon, the most dangerous is that the war let the Shi’ites out of the bottle. No one predicted it; I couldn’t find it in any intelligence report.’[35] Similarly, in Iraq ‘[Muqtada al-Sadr’s] rise to prominence within the Shi’a community largely went unnoticed by the United States government’, says Timothy Haugh.[36] These conclusions are surprising because the movements start their activities in plain sight. Haugh writes, ‘As U.S. tanks dashed across Iraq, Muqtada al-Sadr and his vanguard of like-minded clerics reactivated mosques, deployed a militia, assumed control of regional Ba’ath Party institutions, and prepared social services.’[37] Similarly ‘Muqtada demonstrated his ability to reflect and channel inchoate popular feelings as early as his first Friday prayer (al-Khutba), delivered in Kufa on 11 April 2003. He asked Shiites to express their piety by undertaking a pilgrimage to Karbala… Coming on the heels of the regime’s fall, the massive celebrations offered Shiites a first opportunity to see and measure their new, colossal force.’[38] The success of these movements is linked to the fact that their visible, massive social and charitable activities are not targeted because they are not recognized as being preparations for armed resistance. However, once these activities generate popular support, they allow the movement to hide armed groups among the population and protect them from being targeted.

The combination of an armed vanguard and solid popular support allowed Hezbollah to withstand the IDF in 2006. Hezbollah was able to combine two capabilities. The first was to survive the actions of the IDF land forces on their territory. The second was the ability to maintain a constant barrage of rockets on Northern Israel. According to the Israeli government, ‘During Hezbollah’s month-long bombardment of Israel’s civilian population, 6,000 homes were hit, 300,000 residents displaced and more than a million were forced to live in shelters. Almost a third of Israel’s population – over two million people – were directly exposed to the missile threat.’[39] The Commission to Investigate the Lebanon Campaign called this a severe failing. ‘The barrage of rockets aimed at Israel’s civilian population lasted throughout the war, and the IDF did not provide an effective response to it,’ the government admitted.[40]

Hezbollah used clever tactics to avoid being a target. As Matt Matthews found, ‘Hezbollah established a simple, yet effective system for firing the Katyusha rockets. Once lookouts declared the area free of Israeli aircraft, a small group moved to the launch site, set up the launcher, and quickly departed. A second group would then transport the rocket to the launch location and promptly disperse. A third small squad would then arrive at the location and prepare the rocket for firing, often using remotely controlled or timer-based mechanisms. The entire process was to take less than 28 seconds with many of the rocket squads riding bicycles to the launch location.’ [41] Beside this tactical aspect, the strategic importance of Hezbollah’s approach was that no command and control were needed to conduct operations. This led an Israeli officer to define Boyd’s OODA loop differently: ‘The Hezbollah fighter wakes up in the morning, drinks his coffee, takes a rocket out of his closet, goes to his neighbor’s yard, sticks a clock timer on it, goes back home and then watches CNN to see where it lands.’[42] Hezbollah simply had nothing it could not afford to lose. An Israeli analyst captured this reality well by choosing Breaking the Amoeba’s Bones as the title for his study of the 2006 war. According to him, ‘Hizbollah does not have an operational center of gravity whose destruction would lead to the collapse of the organization.’[43]

In 2000 the Otpor movement in Serbia proved the effectiveness of a more drastic form of not being a target: non-violence. Photo ANP/Hollandse Hoogte, John Schaffer

A more drastic form of not being a target is being non-violent. Events in Serbia in 2000 illustrate its effectiveness. During a press conference on 4 November 1999, US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright stated that ‘All Serbs should know that the day they succeed in restoring democracy is the day Serbia’s isolation will end.’[44] The press conference came after a meeting with members of the Serbian opposition. Albright also said that ‘the administration’s first objective is to strengthen Milosevic’s political opponents’.[45] A year later, Milosevic resigned after a crescendo of protests that culminated in a march of hundreds of thousands towards the capital Belgrade. The protests that led to his downfall were organized by a movement called Otpor (resistance). It turned out later that key figures had received training organized and financed by American organizations. Their strategy was based on a handbook written by American political scientist Gene Sharp.[46] The handbook contained a coherent whole of 198 ‘methods of nonviolent action’.[47] Sharp’s nonviolence had nothing to do with faintheartedness: ‘My key principle is not ethical. It has nothing to do with pacifism. It is based on an analysis of power in a dictatorship and how to break it by withdrawing the obedience of citizens’ (emphasis added).[48] When one thinks this trough, withdrawing obedience is a purer form of parallel warfare than Warden’s physical destruction of enemy command systems or Boyd’s operations inside the adversary’s OODA loops. Also, considering the fact that American aid to Otpor only amounted to 25 million dollars, it comes at a fraction of the cost.

The examples above describe a wide variety of approaches to waging an armed conflict against a stronger opponent. However, they have some elements in common. Mastering the art of not being a target hinges on the ability to combine massive mobilization and coercive action with the absence of centralized leadership and institutional decision making. It’s all about creating as many cooperative centers of gravity as possible while accepting the loss of any of them.

Co-opting the art of not being a target

That the American government could help bring down an unpopular foreign president without putting a single American soldier or citizen in harm’s way did not go unnoticed in the Russian Federation. After the ousting of Serbian president Milosevic by Otpor, several similar successful campaigns took place in the periphery of Russia.[49] The Kremlin quickly grew suspicious of these events, especially when a similar movement started in Moscow in 2011.

The revolutions sparked a research endeavour by the Russian defence and security apparatus. They realized that this was a vital threat to their power. What worried them was the fact they did not have a concept to defend themselves against these types of movements. In 2013 Russian Chief of Staff General Valery Gerasimov wrote an article warning that ‘a perfectly thriving state can, in a matter of months and even days, be transformed into an arena of fierce armed conflict.’[50] After the Maidan Revolution in Ukraine in 2014, Moscow devoted the entire yearly security conference to the theme of colour revolutions. During the conference, Gerasimov defined the threat as follows: ‘Colour Revolutions have become the main lever for the realization of political ideas… They are based on political strategies involving the external manipulation of the protest potential of the population, coupled with political, economic, humanitarian, and other non-military measures.’[51]

The approaches proposed at the conference were based on the fact that not being a target requires mass mobilization. It all starts with a battle of ideas. The main motivating factor behind the revolutions in the Russian periphery was the wish to live in a Western liberal democracy and economy. Russian leader Vladimir Putin realized that he needed to discredit the Western lifestyle and to promote a distinct Russian way of life. He needed proof that the Russian world was different to, superior to and incompatible with the Western world. The basic idea is what Lien Verpoest and Eva Claessen call ‘geopolitical othering’.[52] It involves opposing Western cultural and moral values to Russian ones. In this process, ‘politicians and policymakers [stress] the importance of traditional values, patriotism and history, backed up by the state media and new legislation (anti-gay propaganda, anti-blasphemy law, foreign agents law).’[53]

People stand in line outside the office of a Russian cell phone operator to get a new number in the Crimean city of Simferopol in August 2014: without using the manoeuvrist approach and by spreading a narrative of geopolitical 'othering', Russia managed to take over the region. Photo ANP/AFP, Max Vetrov

Putin articulated his vision in his 2013 State of the Union: ‘Today, many nations are revising their moral values and ethical norms, eroding ethnic traditions and differences between peoples and cultures. Society is now required not only to recognize everyone’s right to the freedom of consciousness, political views, and privacy, but also to accept without question the equality of good and evil, strange as it seems, concepts that are opposite in meaning… Of course, this is a conservative position. But speaking in the words of Nikolai Berdyaev, the point of conservatism is not that it prevents movement forward and upward, but that it prevents movement backward and downward, into chaotic darkness and a return to a primitive state. In recent years, we have seen how attempts to push supposedly more progressive development models onto other nations actually resulted in regression, barbarity and extensive bloodshed.’[54] In the years following the 2011 elections the state media constantly spread a narrative that portrays Russia as a beacon of moral superiority that is fundamentally different from the ‘degenerate’ West. The West is a geopolitically ‘other’ world, incompatible with the Russian one.

This approach was successful in 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea. In a television documentary masde a year later, Putin explains in detail how the combination of a pro-Russian narrative and a deniable military presence enabled Russia to annex the region in one month almost without firing a shot.[55] He also revealed that he took his final decision about Crimea ‘after secret, undated opinion polls showed 80 percent of Crimeans favored joining Russia,’ [56] thus confirming that popular support is a prerequisite for military success.

Conclusion

Western military, political and social thought on armed conflicts rests on increasingly shaky foundations. All too often this thought starts with assumptions about technological superiority allowing surgical targeting of capabilities that the enemy cannot afford to lose. Recent outcomes of armed conflicts show that these assumptions no longer hold true. When Western theorists acknowledge this, they often attribute the evolution to technological changes such as the proliferation of weaponized gadgets (like home-made rockets) to previously weak actors. They then propose to focus efforts on the development of even higher-tech countermeasures. These proposals are dead-end approaches, promising only temporarily relief.

The real truth is that the manoeuvrist approach is not always applicable. Popular support allows opponents to avoid having targets in the shape of critical vulnerabilities and other points of influence. The implication is that operational planning needs to start with the questions whether it is possible to gain the support of the people living in the conflict area or whether popular support can be denied to the adversary. When the answer to one or both questions is ‘no,’ then the harsh conclusion is that the operation will either fail or result in an endlessly protracted stalemate.

[1] NATO, Allied Joint Doctrine Edition F Version 1 (Brussels, NATO Standardization Office, December 2022) 82. See: https://nso.nato.int/nso/nsdd/main/standards?search=AJP-01.

[2] Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War. Translated by Martin Hammond and P. J. Rhodes (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2009) Preface, 4.

[3] See: Merriam-Webster, ‘Target’, definition and meaning.

[4] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Translated and edited by Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989) 485.

[5] Samuel J. Newland, Victories are Not Enough (Carlisle, U.S. Army War College Press, 2005) 19. See:

https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/370.

[6] John A. Warden III, ‘The Enemy as a System,’ Airpower Journal, Vol. IX, No. 1 (Spring 1995) 54. See: https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ/journals/Volume-09_Issue-1-Se/1995_Vol9_No1.pdf.

[7] Ibid., 42.

[8] Ibid., 52.

[9] Ibid., 54.

[10] John R. Boyd, A Discourse on Winning and Losing. Edited and compiled by dr. Grant T. Hammond (Maxwell Air Force Base, Air University Press, 2018) 224.

[11] Ibid., 237.

[12] Statement Issued at the Extraordinary Ministerial Meeting of the North Atlantic Council held at NATO Headquarters, Brussels, on 12th April 1999 (Brussels, NATO, 12th April 1999). See: https://www.nato.int/docu/pr/1999/p99-051e.htm.

[13] Anthony H. Cordesman, The Lessons and Non-Lessons of the Air and Missile Campaign in Kosovo (Washington, D.C., Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2003) 15. See: https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/media/csis/pubs/kosovolessons-full.pdf.

[14] Ibid., 118.

[15] Warden, ‘The Enemy as a System’, 49.

[16] Geoffrey Wawro, The Franco-Prussian War (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003) 232.

[17] Ibid., 237.

[18] Warden, ‘The Enemy as a System’, 53.

[19] Ibid., 50.

[20] Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke, Reichstag 16 February 1874. See: https://www.projekt-gutenberg.org/bebel/auslebe2/chap035.html.

[21] Thucydides, The Landmark Thucydides. A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War,

Robert B. Strassler (ed.), translated by Richard Crawley (New York, Free Press, 1996) 352.

[22] Mao Tse-tung, Translated with an introduction by Brigadier General Samuel B. Griffith, On Guerrilla Warfare (Washington, D.C., Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, 1989) 52.

[23] Ibid., 27.

[24] Ibid., 46.

[25] Ibid., 18.

[26] Richard P. Mitchell, The Society of the Muslim Brothers (London, Oxford University Press, 1969) 308.

[27] Gilles Kepel, Jihad: expansion et déclin de l’islamisme (Paris, Editions Gallimard, 2000) 29.

[28] Gilles Kepel, ‘Islamists Versus the State in Egypt and Algeria’, Daedalus, Vol. 124, No. 3, 110.

[29] Özlem Tür Kavli, ‘Islamic Movements in the Middle East: Egypt as a Case Study,’ Perceptions, Journal of International Affairs, Vol. VI, No. 4. (December 2001-February 2002)

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Sayyid Qutb, Milestones (New Delhi, Islamic Book Services, 2015) 75.

[34] Ladan Boroumand and Roya Boroumand, ‘Terror, Islam, and Democracy,’ Journal of Democracy, Volume 13, No. 2 (April 2002) 5-20. See: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Boroumand.pdf.

[35] Yitzhak Rabin, quoted by Robin Wright, Sacred Rage. The Wrath of Militant Islam (New York, Touchstone, 2001) 233.

[36] Timothy Haugh, ‘The Sadr II Movement. An Organizational Fight for Legitimacy within the Iraqi Shi’a

Community,’ Strategic Insights, Vol. 4, No. 5 (May 2005) 1-10. See: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235189998_The_Sadr_II_Movement_An_Organizational_Fight_for_Legitimacy_within_the_Iraqi_Shi%27a_Community.

[37] Ibidem.

[38] Timothy Haugh, ‘Iraq’s Muqtada Al-Sadr: Spoiler or Stabiliser?’, Internatioal Crisis Group Middle East Report No. 55 (11 July 2006). See: https://icg-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/55-iraq-s-muqtada-al-sadr-spoiler-or-stabiliser.pdf.

[39] Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Second Lebanon War (2006) (12 July 2006). See: https://www.gov.il/en/Departments/General/hizbullah-attack-in-northern-israel-and-israels-response-12-jul-2006.

[40] Winograd Commission, Final Report (30 January 2008). See: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/winograd-commission-final-report-january-2008.

[41] Matt M. Matthews, We Were Caught Unprepared. The 2006 Hezbollah-Israeli War (Fort Leavenworth, U.S. Army Combined Arms Center, Combat Studies Institute, 2008) 17.

[42] LTC Ishai Efroni Deputy Commander, Baram Brigade quoted in: Jonathan Finer and Edward Cody, ‘Hezbollah Unleashes Fiery Barrage 230 Rockets Strike Northern Israel, Shattering Brief Lull,’ Washington Post (3 August 2006. See: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2006/08/03/hezbollah-unleashes-fiery-barrage-span-classbankhead230-rockets-strike-northern-israel-shattering-brief-lullspan/1b2c921a-cee1-4a61-b297-23db40b995c7/.s

[43] Ron Tira, ‘Breaking the Amoeba’s Bones,’ Strategic Assessment, Vol. 9, No. 3 (November 2006) 1-15. See: https://www.inss.org.il/strategic_assessment/breaking-the-amoebas-bones/.

[44] ‘Statement by Secretary of State Mrs. Madeleine Albright’, Associated Press (4 November 1999). See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8CBNXTPX_LI.

[45] Norman Kempster, ‘U.S. Offers Aid if Yugoslavia Has Elections,’ Los Angeles Times (4 November 1999). See: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-nov-04-mn-29940-story.html.

[46] Gene Sharp, The Politics of Nonviolent Action (New York, Porter Sargent, 1974).

[47] For the complete list, see the Albert Einstein Institution: https://www.brandeis.edu/peace-conflict/pdfs/198-methods-non-violent-action.pdf.

[48] Gene Sharp, quoted in: Roger Cohen, ‘Who Really Brought Down Milosevic?,’ The New York Times Magazine 26 November 2000. See: https://www.nytimes.com/2000/11/26/magazine/who-really-brought-down-milosevic.html.

[49] The so-called Colour Revolutions took place in Georgia (2003, Rose Revolution), Ukraine (2004, Orange Revolution), and Kyrgyzstan (2005, Tulip Revolution). See: A.S. Brychkov and G.A. Nikonorov, ‘Color Revolutions in Russia. Possibility and Reality,’ Vestnik Akademii Voennykh Nauk [Journal of the Academy of Military Sciences] 3 (60) (2017) 4-9. For a translation by Boris Vainer see: https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/Hot%20Spots/Documents/Russia/Color-Revolutions-Brychkov-Nikonorov.pdf.

[50] Valery Gerasimov, ‘The value of science is in the foresight. New challenges demand rethinking the forms and methods of carrying out combat operations,’ Military-Industrial Kurier (27 February 2013), translation by Robert Coalson, Military Review 96, No. 1 (2016) 23.

[51] Valery Gerasimov, “On the Role of Military Force in Modern Conflicts,” Report of the Third Moscow Conference on International Security, Conference Materials, ed. A.I. Antonov, (Moscow: The Ministry of

Defence of the Russian Federation, 2014), 15.

[52] Lien Verpoest and Eva Claessen “Liberalism in Russia: from the margins of Russian politics to an instrument of geopolitical othering,” Global Affairs, (2017) 3:4-5, 337-352, DOI:

10.1080/23340460.2017.1449601

[53] Ibid.

[54] Vladimir Putin, (2013, December 12). Address to the Federal Assembly. Prezident Rossii, Retrieved

[55] A. Kondrashov, (Director), The Path to the Motherland (documentary, 2015). Rossiya 1. Original title: Крым. Путь на Родину. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N-ttlj-T2Uc.

[56] A. Kondrashov, ‘Putin reveals secrets of Russia's Crimea take-over plot,’ BBC News (9 March 2015). See: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-31796226.