Future operations for gendarmerie organisations, like the Royal Netherlands Marechaussee, are becoming more and more joint, inter-agency, and multinational in nature, thus asking for cooperation between the players in the field. In this light, international cooperation programmes can have a positive contribution to these types of future operations. This article explores three concepts that gendarmeries, but also other armed services, can use to develop these international cooperation programmes: the international cooperation triangle, the factors of interoperability, and the cooperation pyramid. Well-designed and well-managed cooperation programmes in peacetime can enhance interoperability and reduce frictions during multinational operations, with increased mission effectiveness as a result.

Capt. A.L. Heijboer MSc*

Any officer who has ever been invited to an international event, knows how to seek out the most alluring activities in the programme: the cultural event and the hosted dinner. Although often joked about amongst the attendees, these activities actually play an integral and important role in building international cooperation.

International cooperation plays a vital role in today’s warfare and missions abroad. Military operations are more and more a multinational and interagency affair for various reasons, such as complementarity of necessary capabilities and capacities to accomplish the mission or political legitimacy.

However, the multinational execution of these operations add ‘an often-overlooked layer of complexity that can have a significant negative impact on operations if not managed carefully’.[1] International cooperation faces difficulties due to language barriers and organisational and cultural differences. These interoperability issues may cause friction and thus have a negative influence on the operational effectiveness of multinational operations and missions.

Managing and solving interoperability friction is done during the execution of operations, but is preferably mitigated during peace time engagement. However, international cooperation is (still) not something that comes naturally and may have high costs. Well managed international cooperation programmes may contribute to this process of acknowledging and mitigating differences amongst participating organisations.

During EUPST 2016 units of the Royal Netherlands Marechaussee are being trained in cooperation. Photo MCD Eva Klijn

This article argues why and how international cooperation programmes can be a positive contribution to future multinational operations. The following analysis of cooperation within the international gendarmerie context is based on three frameworks: the police cooperation triangle; interoperability factors, and the cooperation pyramid. In addition, although it lies outside the scope of this article, these three concepts could also be used to analyse other military organisations within their international context, in order to develop cooperation programmes.

Gendarmerie — international cooperation context

‘Since the beginning of this millennium, the deployment of civil police or gendarmerie in international missions, be it under the UN flag, or in NATO, EU or OSCE [Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe] missions, has gained weight, quantitatively, but also regarding the diversity of tasks and its relative importance compared to military components in crisis management’.[2] The high demand for police personnel for international missions means that a gendarmerie’s personnel most likely will be deployed during their career and that they have to be able to work together with colleagues from different countries and different organisations.

All gendarmerie forces perform (some) police duties and share military characteristics. Photo MCD, Maartje Roos

There is a variety of gendarmerie organisations across the world and none of them are exactly the same; in addition, there is no unambiguous definition of a gendarmerie force. However, ‘all gendarmerie forces have in common that they perform (some) police duties and share military characteristics organized along military lines (centralized and hierarchical), heavier weaponry and equipment, robust, group cohesion, military legal status enabling flexibility, military code, and versatility’.[3]

The specific characteristics of gendarmeries enable them to play a role in both the military and civilian (police) worlds and enable them to act as a linchpin between military and civilian (police) organisations.[4] This means that international cooperation also takes place in both the military and civilian police world, and that within these two types of organisations, there can be differentiation of focus on countries, partners, organisations, and aim of the cooperation.

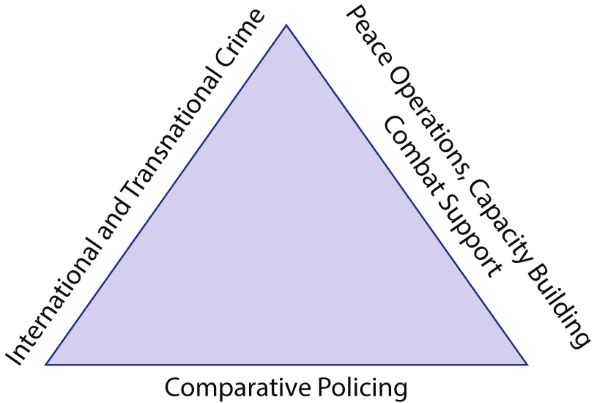

This differentiation can be seen in Casey’s ‘Triangle of International Policing’,[5] in which he describes three key areas of the international dimension of policing. The first dimension forms the basis of international cooperation and consists of the discipline of comparative policing. Comparative policing studies policing in other countries in order to broaden the understanding of policing policies and operational strategies. Without international comparative policing, the knowledge of available options won’t be more than that of policing organisations within a country and the lower regional levels these organisations have.[6]

The second dimension consists of international and transnational crime and the international policing strategies that are emerging to respond to new threats. The third dimension is the analysis of the work of police forces in peace operations and capacity building in post-conflict and developing countries. For gendarmeries with military policing tasks, the combat support role can also be added in this side of the triangle.

Figure 1 Casey’s triangle of international policing (modified)

Gendarmeries operate within all three dimensions, because of their civilian and military characteristics. Comparative policing can be done with sister gendarmerie forces, civilian police, or military police organisations, depending on the field of interest. The international and transnational crime dimension is more focused on the civilian policing side of gendarmeries, whereas peace operations, capacity building, and combat support takes place within the military environment.

Although all three dimensions are important for gendarmeries, the scope of this essay is comparative policing and the triangle side of peace operations, capacity building, and combat support. Furthermore, it should be taken into account that this essay is written from a European perspective.

Future missions and the call for interoperability

Due to the complexity of security missions, peace operations, and stabilization missions along with the broad spectrum of organisations involved and capabilities needed, most contemporary and future gendarmerie missions are conducted in a joint, interagency or multinational framework. The United States Department of Defense defines multinational operations as ‘military actions conducted by forces of two or more nations, usually undertaken within the structure of a coalition or alliance’.[7]

Royal Netherlands Marechaussee exercise with their Spanish counterparts of the Guardia Civil. Photo MCD, Jasper Verolme

There are two fundamental reasons why nations want to conduct multinational operations. The first is a very practical one, namely ‘to bring together the combination of capabilities necessary to achieve the end shared by its members’.[8] The second reason is to create diplomatic legitimacy: ‘Politically, a coalition, especially a broadly based one, will be perceived by the international community as acting with greater legitimacy than the actions of a single state, especially if the coalition is supported by an international mandate such as a United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution’.[9]

Although multinational operations are the preferred option, it also makes these operations more complex than unilateral ones. Culture, mind-set, philosophy, national advantages, doctrine, training, and so on can lead to coalition friction. Enhancing interoperability can decrease these frictions and positively influence the effectiveness of the mission.

Therefore, interoperability within the multinational environment is important and desired. One of the organisations that emphasize the importance of interoperability is NATO, whose definition of interoperability is:

‘The ability for Allies to act together coherently, effectively and efficiently to achieve tactical, operational and strategic objectives. Especially, it enables forces, units and/or systems to operate together and allows them to share common doctrine and procedures, each other’s infrastructure and bases, and be able to communicate. Interoperability reduces duplication, enables pooling of resources, and produces synergies amongst the [29][10] Allies and whenever possible partner countries’.[11]

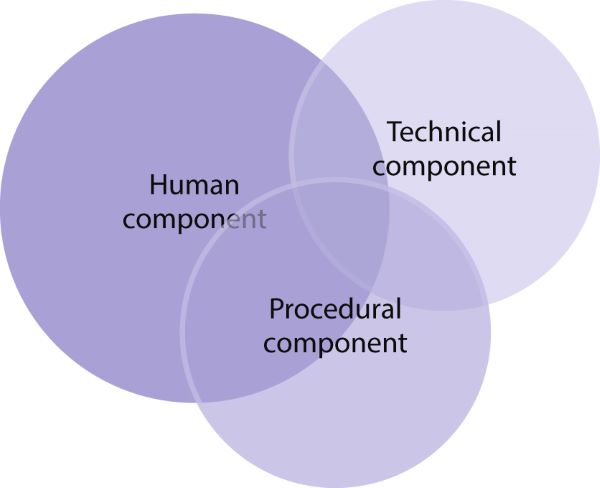

Furthermore, NATO describes three components of interoperability: the technical, the procedural, and the human component. Improving technical and procedural interoperability is necessary, but not enough. It is the human component which is mostly linked to effective interoperability.[12]

The human component is mostly influenced by cultural factors and, as such, knowledge about intercultural aspects is therefore paramount to the success of multinational operations.[13] Developing the human component through maintaining close interpersonal relationships creates trust and the will to work together, to solve problems, and to enable successful cooperative activities. These relationships develop mostly because of acquired common experience through exchange and joint activities. In these interactions, the quality of the activities is more important than the quantity.[14]

Figure 2 Interoperability components

Enhancing interoperability through international cooperation programmes

One of the ways to create common experiences and activities is through international cooperation programmes. International cooperation can take place at several levels, from the diplomatic and strategic level down to the tactical and operational level, and can have different objectives.

At the diplomatic and strategic level, the objectives could be to develop and maintain international relations, obtaining legitimacy for international operations, and influencing decision-making processes. Good relationships between parties at the strategic level are important to allow cooperation at the lower levels. Cooperation at the tactical and operational level contributes to maintaining international relations, but often also includes more concrete activities aiming towards enhancing operational execution or the development and improvement of all the organisations involved.

Furthermore, cooperation programmes can take place within the operational and institutional domain, in various ways and at various levels of intensity. Some examples include joint research projects, information and knowledge exchange, cooperation and exchange in the field of education and training, and conducting multinational exercises and operations up to fully integrated units.

International police and military police units exercise aspects of ‘High Risk Security’. Photo MCD, Sjoerd Hilckmann

However, cooperation programmes do not execute themselves and certain conditions make cooperation programmes more or less successful. Depending on the goals of the cooperation, one of the conditions is that the right contacts and a good quality of relationships exist. Secondly, the activities must be managed. When these two conditions are met, the most positive effects can be expected.

Regular evaluation and adjustment are necessary, and seem to open doors. However, the benefits of cooperation are often hidden in indirect results; therefore, it is important to manage programmes carefully. Activities of international cooperation are often not embedded in the routine work of an organisation, but often do encompass, and affect, multiple areas of focus, effort, and units. Therefore, programme management is an appropriate management method for international cooperation.[15]

Cooperation programmes: building the international cooperation pyramid

A cooperation programme may exist of a variety of joint activities, depending on the objectives. The activities may vary in intensity and one must take into account that, first of all, a solid basis needs to be established as the foundation of the cooperation. A possible grouping of activities can be seen in the figure below (figure 3).[16]

International cooperation can be formal or informal, but in practice, police cooperation is hybrid and a mixture of both. Informal contacts and individual operational initiatives can gradually transform into formal agreements or organisations.[17] However, the most important ingredient for international cooperation is trust[18] and police officers favour the use of trusted informal networks, which were built via face-to-face interaction through training courses, conferences or bi- or multilateral cooperation.[19]

The pyramid is founded on the idea that relationships and trust form the basis of international cooperation and that cooperation activities vary from simple to more complex activities in terms of coordination, organisation, resources, et cetera.

Figure 3 International cooperation pyramid

The basis of cooperation is formed by maintaining international relations and contacts. These relations do not necessarily have to deal with substantive issues, but allow for agreements on cooperation programmes and activities. Even in periods of fewer activities, it is wise to keep regular contact with partners for possible future opportunities. These contacts may comprise of yearly meetings, staff talks, visits or attending ceremonies, et cetera.

Relationship management is the key word at the lowest level of the pyramid. Maintaining these relations and recognition of their importance is often seen in hosted dinners, receptions, demonstrations, static shows or cultural events. These activities are beneficial to build necessary relationships in a more informal way.

Although the other levels of cooperation also contribute to maintaining relations, the aim of these activities is to reach more substantive results. The level of joint research, information, and knowledge exchange is relatively easy to organize and execute in both existing and new structures.

One step further is the use of each other’s education and training possibilities, or in joint development activities, and executing missions. Countries could use each other’s facilities, when they do not have the capacity or capability themselves or when it is not viable to invest in their own expensive facilities. Furthermore, they can use education and training in foreign countries for personnel development. These forms of cooperation often ask for more investments and a formal agreement rather than just exchanging knowledge and information.

Gendarmeries can contribute to multinational operations within NATO, UN, or EU frameworks. Photo Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs

An even deeper level of cooperation exists when partners choose to conduct exercises together. Exercises are very common in the military world, but less so in the policing world, especially large scale live exercises. This is because they require a lot of effort in resources and knowledge, compared to a short training.

Exercises may have the aim to prepare personnel for an upcoming deployment, but also to learn from each other. Exercises can be conducted in a multilateral setting, such as a NATO exercise, or be organised by individual countries bilaterally. Organising and executing an exercise together in itself also contributes to cooperation and the improvement of interoperability.

The next level is multinational operations. These operations may consist of policing support to military, peace support operations, and capacity building within NATO, the UN or EU. The ‘highest’ level of cooperation is attained when units or personnel of different countries or organisations are integrated in the same unit or organisation. Especially when these units have to conduct operations in conflict areas, there must be a solid basis of trust, relationships, knowledge, education, training and exercise, in order to reduce risks.

International and foreign postings

Personnel at international and foreign positions play an important role in support of the pyramid’s activity levels. Besides the fact that international and foreign postings are among the most visible forms of cooperation, these people act as linchpins and provide (easy) access to the organisation they work for or within.

When it comes to international postings, there are roughly two options. On the one hand personnel may fulfil a position abroad, but stay in the chain of command of their mother organisation. In these cases, the person acts as a liaison officer, i.e. the point of contact for communication and coordination of activities between the two organisations.

On the other hand, personnel work for an international or sister organisation and fulfil a specific function within this other organisation. Examples are the Provost Marshal within NATO or an exchange officer with a sister MP or gendarmerie organisation. In principle, the personnel are ‘given away’ by the mother organisation, but it is also known that these people also function as a point of contact.

Integrated police exercise in Italy, during EUPST 2016. Photo MCD, Eva Klijn

The personnel for these functions should be carefully chosen since they represent their country and their mother organisation, and have to be culturally sensitive when working in a different environment. Due to their position, these officers have access to certain information and are therefore able to identify new possibilities and viable opportunities for cooperation. They might be able to influence decision making processes, sooth out problems and misunderstandings, support the execution of programmes, and build and maintain the right and necessary relationships and contacts as one of the conditions for successful programmes. In short, they play an important role in international cooperation, because of the earlier mentioned preference for trusted partners and networks.

Current gendarmerie cooperation

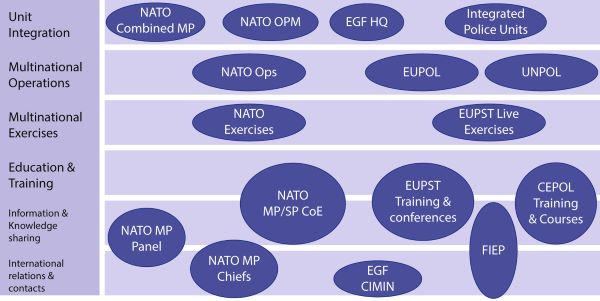

The cooperation pyramid can be used to analyse voids or set up new cooperation programmes, by mapping activities. Figure 4 shows some of the current examples of international cooperation activities, related to the international gendarmerie context.

Figure 4 International cooperation map

Within the NATO structure, gendarmerie organisations participate in regular NATO meetings such as the NATO Military Police Chiefs’ Conference (MPCC) and the NATO Military Police Panel (MPP). Furthermore, personnel are stationed at the Military Police Centre of Excellence (MPCoE) and the Stability Policing Centre of Excellence (SPCoE). Gendarmerie personnel participate in NATO-led exercises and operations and within the various Offices of the Provost Marshal (OPM). NATO also understands the concept of combined military police and multinational integrated units that may consist of MPs and gendarmes.

The European Gendarmerie Force (EUROGENDFOR) is a multinational cooperation between European gendarmerie forces. The organisation is governed by the Higher Inter-ministerial Committee (CIMIN) and its operational headquarters in Italy (EUROGENDFOR/EGF HQ). Individual personnel of the EGF HQ participated in exercises and have been deployed under the umbrella of the EUROGENDFOR. In the past the EUROGENDFOR HQ organized and conducted exercises for its member nations and more recently it has decided to organize an annual live exercise.[20]

The European Union Police Services Training programme (EUPST) is an EU initiative to train police personnel for EU police missions, through a series of training activities, live exercises, conferences, and curricula development. The EUPST I (2011-2013) and EUPST II (2015-2018) programmes both consisted of live exercises, such as the exercise Lowlands Grenade. The third iteration of the programme will also include civilians and therefore the name changed into EU Police and Civilian Services Training (EUPCST) and will most likely not contain live exercises anymore.

The International Association of Gendarmeries and Police Forces with a military status (FIEP), focuses on information and knowledge exchange on certain topics. The FIEP not only consists of European gendarmeries forces, but also has members from all over the world.[21]

CEPOL is the EU Agency for Law Enforcement Training and is dedicated to develop, implement, and coordinate training for law enforcement officials.[22] It provides education and training and it has a science and research pillar. Some of CEPOL’s activities are specialised toward police missions abroad.

Besides NATO operations, gendarmes also participate in UN Police (UNPOL) and EU Police (EUPOL) missions, the so-called Civilian Police (CIVPOL) missions. They can do so on an individual basis as Individual police Officers (IPO’s) or in Integrated Police Units (EU) or Formed Police Units (UN).

International police and gendarmerie units exercise together, such as exercise Lowlands Grenade. Photo MCD, Eva Klijn

The cooperation map shows that European gendarmeries participate in a variety of cooperation activities and that the NATO structure is well developed throughout the whole pyramid. The EUPST programme filled a void regarding live exercises for police services, and if the new programme does not contain these multinational exercises anymore, this could be a void for gendarmeries to fill together. The EUROGENDFOR CIMIN decision in December 2018 to conduct an annual EUROGENDFOR live exercise is a promising and valuable contribution.

Conclusion

This essay has tried to explain that well designed and managed peacetime cooperation programmes may contribute to mitigating friction issues during multinational operations and thus influence effectiveness. The international police cooperation triangle, the interoperability factors to be influenced, and the cooperation pyramid are tools that gendarmerie and other services of the armed forces can use to develop beneficial and meaningful cooperation programmes for the future.

* Anne Heijboer is Staff Officer at the Royal Netherlands Marechaussee National Centre for Training and Expertise.

[1] K.J. McInnis, ‘Lessons in coalition warfare: past, present and implications for the future’, in: International Politics Reviews 1 (2013) (2) 78-90.

[2] F. van der Laan, L. van de Goor, R. Hendriks, J. van der Lijn, M. Meijnders, D. Zandee, ‘ The Future of Police Missions’, Clingendael Report (2016) 12.

[3] H. Hovens, ‘The Future Role of Gendarmeries in National and International Contexts’, in Vittorio Stingo, Michael J. Dziedzic and Bianca Arbu (eds.), Stability Policing: A toolkit to project stability, Headquarters Supreme Allied Commander Transformation (2017).

[4] M. de Weger, ‘The Rise of the Gendarmes? What really Happened in Holland?’, in: Connections: The Quarterly Journal 08 (2008) 92.

[5] J. Casey, Policing the World. The Practice of International and Transnational Policing (Durham, Carolina Academic Press, 2010) xvii-xviii.

[6] Ibidem 3.

[7] U.S. Department of Defense, Joint Publication 1-02. DoD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (2017) 159.

[8] Russell W. Glenn, Band of brothers or Dysfunctional family? A military perspective on coalition Challenges During Stability Operations (Rand Corporation, 2011) 4.

[9] Ibidem 4-5.

[10] Montenegro became NATO’s 29th member on 5 June 2017.

[11] See http://www.natolibguides.info/interoperability.

[12] D.A Gamble and M.M.T. Letcher, ‘The Three Dimensions of Interoperability for Multinational Training at the JMRC’, in: Army Sustainment September-October 2016.

[13] NATO, Multinational Military Operations and Intercultural factors (2008) 9-1.

[14] Luft (2009) in K.J. McInnis, Lessons in Coalition Warfare: past, present and implications for the future, 84.

[15] See www.werkenaanprogrammas.nl.

[16] This pyramid is the newest (modified) version of the pyramid described in: A.L. Judge-Heijboer, Closing NATO Policing gaps together: multinational force interoperability between the Royal Netherlands Marechaussee and the United States Army Military Police (2017).

[17] B. Bowling, Policing the Caribbean. Transnational Security Cooperation in Practice (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010); L. Guile, ‘Police and judicial cooperation in Europe: bilateral versus multilateral cooperation’, in: Fredric Lemieux (ed.) International Police Cooperation, Emerging Issues, Theory and Practice (2010).

[18] L. Guile, ‘Police and judicial cooperation in Europe: bilateral versus multilateral cooperation’, in: Fredric Lemieux (ed.) International Police Cooperation, Emerging Issues, Theory and Practice (2010) 34-35.

[19] Bowling, Policing the Caribbean; Guile, ‘Police and Judicial Cooperation in Europe’; F. Lemieux, ‘The nature and structure of international police cooperation: an introduction’, in: Fredric Lemieux (ed.) International Police Cooperation, Emerging Issues, Theory and Practice 52; M. den Boer, ‘Towards a governance model of police cooperation in Europe: the twist between networks and bureaucracies’ in: Fredric Lemieux (ed.) International Police Cooperation, Emerging Issues, Theory and Practice 47.

[20] CIMIN Meeting, 13 December 2018.

[21] See www.fiep.org.

[22] See www.cepol.europa.eu.