This autumn, 75 years ago, Canadian and British forces liberated both shores of the Westerschelde, the waterway connecting the North Sea to the port of Antwerp. The victory, realised after heavy fighting, opened up a critical supply route to the Allied Expeditionary Force for its offensive into Germany. Two articles will be dedicated to the Battle of the Westerschelde, the first of which, focusing on the impact of military-strategic decision-making, is published in this issue of the Militaire Spectator.

Dick Zandee*

In late August 1944 Allied forces crossed the River Seine after the German Army had been defeated in Normandy. On 4 September British tanks drove into Antwerp with its port fully intact. What had become the biggest problem for the Allied forces – logistical supply over long roads from the Normandy coast to the new front line – could soon be solved. The port of Antwerp not only had the capacity to supply the total force needed for attacking Germany, it was also close to the new front line near the Dutch and German borders. There was one problem: to reach the port ships had to sail the 60 kilometre long Westerschelde waterway. German coastal batteries on both shores of the entrance of the waterway in the Dutch province of Zeeland could hit any ship on its way to Antwerp. It would take more than two months and heavy fighting before the last German forces in the area surrendered to the Allied liberators. Why was so much time needed to defeat the enemy? One explanation relates to the battle itself, which lasted for more than four weeks in October and early November 1944.[1] Another important reason is the delay in commencing the attack, which was the consequence of the military-strategic decision-making with regard to the priorities of the Allied campaign after the Normandy break-out. This article explains how the lack of unity on the strategic priorities impacted on the Battle of the Westerschelde.

Terrapin and Buffalo amphibous vehicles at Terneuzen, October 1944. Photo Library and Archives of Canada

The Normandy break-out

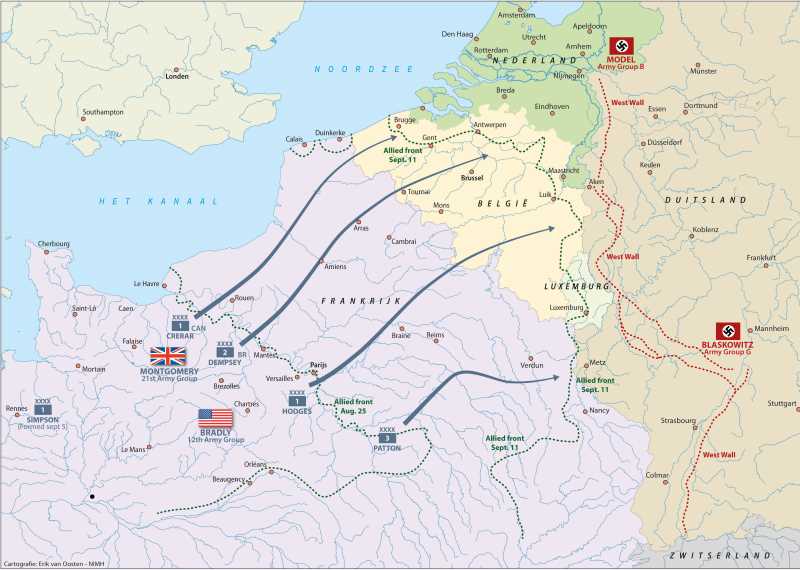

After more than eleven weeks of heavy fighting since D-Day (6 June 1944), the Allied Expeditionary Force (AEF) had defeated the German Army in Normandy. On 29 August, the 21st British Army Group, under the command of General Bernard Law Montgomery, crossed the Seine. The 1st Canadian Army followed the route along the Channel coast, while the 2nd British Army was heading north on the Arras-Lille-Brussels-Antwerp line. East of the British forces the 12th US Army Group, under the command of Lieutenant-General Omar Bradley, was heading towards the German border: the 1st US Army along a line just north of the Ardennes towards the Liège-Aachen gap and the 3rd US Army heading for Metz, south of the Ardennes (see map 1). Approximately two million soldiers were on the move with the armoured divisions acting as spearhead forces.

Map 1 Allied pursuit to the German border, August 25-September 11, 1944. Cartography Erik van Oosten, NIMH

Logistical supply quickly became a serious problem. Transport capacities had to be scrambled and the ‘Red Ball Express’ system was introduced for prioritising the dense traffic along the roads.[2] Within several days, the distance from the Normandy Mulberry Harbours to the front lines extended to 500 kilometres or more.[3] In the ‘tank race’ north of the Seine the main ports along the Channel coast had been bypassed, leaving their liberation to the infantry divisions. Increasingly, commanders were competing for supplies, in particular fuel. The AEF needed about 40,000 tons of supplies daily. In addition, equipment and materials had to be brought inland for repairing railroads, bridges and other infrastructure destroyed by Allied air attacks or sabotage activities by the resistance. At the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) it became clear that another solution had to be found. The closest and largest available port in Western Europe was Antwerp. It could handle approximately 90,000 tons each day, enough to supply the AEF for its attack on the German homeland. Logically, the SHAEF staff was ‘electrified’ when informed of the liberation of Antwerp with its port facilities being fully available.[4] Optimism must have filled the Headquarters rooms: soon the logistical nightmare could come to an end.

German counter-measures

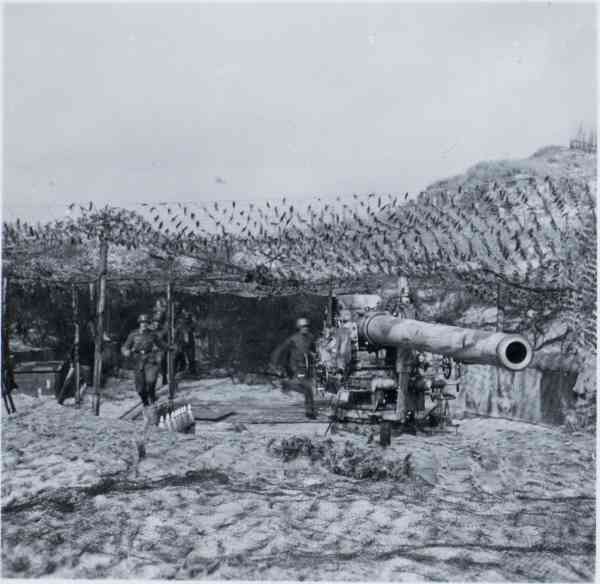

Still the first cargo ships would only sail into the port of Antwerp by the end of November, almost three months after the tanks of the 11th British Armoured Division had driven into the city. One of the causes of the delay is related to the German military counter-measures. The port of Antwerp could not be reached as long as the Germans controlled the mouth of the Westerschelde waterway. On Dutch territory, the point of entry was well-protected by heavy coastal batteries located at Walcheren and in the western part of Zeelandic Flanders (Zeeuws-Vlaanderen).

German 15cm artillery at Dishoek (Walcheren): the port of Antwerp could not be reached as long as the Germans controlled the mouth of the Westerschelde waterway. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

The importance of blocking the Allied use of the port of Antwerp was well-recognised at the German Army High Command.[5] In the early days of September several counter-measures were taken to halt the Allied advance and to strengthen the defence of the Westerschelde. A new defence line was established: the Brabantstellung (Brabant Line) along the Albert Canal from Antwerp to Liège-Maastricht-Aachen. Calais and the island of Walcheren were upgraded to Festungen, to be defended at all costs. Furthermore, the 15th German Army was ordered to retreat via Walcheren and Zuid-Beveland towards North Brabant in order to reinforce the defensive forces at the Brabant Line.[6] The 719th Infantry Division with its headquarters in Dordrecht was ordered to occupy the area north of Albert Canal, where it started to arrive in the afternoon of 5 September. From Germany, approximately 18,000 paratroopers were transported to the Netherlands within days. The 1. Fallschirm Armee (1st Parachute Army), under the command of Generaloberst Kurt Student, was reactivated. Some paratroopers were combined with other forces in ad hoc formations, called Kampfgruppen. These formations, such as the Kampfgruppe Chill, often acted as ‘fire brigades’ every time an Allied breakthrough at the new front line was near. Soon, the paratroopers were able to assist in the efforts to stop the attack of the 2nd British Army just north of the Albert Canal. By 11 September, the front line stabilised on Belgian territory due to strong German defences but also as a result of a shortage of supplies.[7]

Box 1

The 15th German Army had to defend the Channel coast between the Orne river in Normandy and the Westerschelde. After the Allied break-out from Normandy a large part of the 15th Army, commanded by General der Infanterie Gustav-Adolf Von Zangen, managed to retreat along the Channel coast. After the withdrawal behind the (double ) Leopold Canal into Dutch Zeelandic Flanders, a rescue operation was started across the Westerschelde. Despite air attacks by the Royal Air Force, the operation was successful. Between 7 and 23 September approximately 87,000 military, 530 guns, 4,600 vehicles, 4,000 horses and tons of other equipment had reached Between 4 and 21 September 86,100 military, 616 guns, 6,222 vehicles and 6,200 horses had reached the northern shore of the Westerschelde and were transported via Zuid-Beveland to North Brabant.

Several historians have accused Montgomery (and some even Eisenhower) of a strategic mistake by not closing the escape route in early September. The British 11th Armoured Division could have crossed the Albert Canal in Antwerp using the remaining bridge that was still intact. From there 35 kilometres north through almost undefended territory the tanks could have reached the entry/exit point to Zuid-Beveland and Walcheren at the village of Woensdrecht, a few kilometres south of Bergen op Zoom. After the war the Commander of the 11th British Armoured Division, Major-General Richard Roberts, and his superior, Lieutenant-General Sir Brian Horrocks (Commander of the 30th British Army Corps), stated that the Division had enough fuel to advance another 100 kilometres. However, lacking the appropriate intelligence about the 15th Army’s withdrawal across the Westerschelde they had not been aware of the opportunity. It should be noted that such information, gathered by way of the ENIGMA decoding system, was only available to the AEF’s top commanders. The first messages about the retreat of the 15th Army across the Westerschelde became available through ENIGMA decoding on 6 September. By then, the area north of Antwerp had already been reinforced by the arrival of the first German contingents.

The real opportunity for advancing to Bergen op Zoom existed on 4-5 September. Although Roberts and Horrocks suggested after the war that they could have advanced from a logistical point of view, they did not seize the opportunity by their own decision. This was inherent in the British command culture: execute the plan and then stop. Roberts was given the order to liberate Antwerp, which he had accomplished late afternoon on 4 September. No further initiative was taken, neither by him nor by his superior commander. Clearly, it was a missed opportunity for occupying the Woensdrecht entry point to Zuid-Beveland at relatively low cost compared to the three weeks of heavy fighting by the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division in October 1944. Logically, Canadian (military) historians blame the British commanders for a strategic blunder. However, if the early occupation of the entry/exit point to Zuid-Beveland and Walcheren would have shortened the Battle of the Westerschelde remains a matter of speculation. Assuming that the larger part of the 15th German Army would be stuck on the northern shore of the Westerschelde (transportation by boats towards Dordrecht would have taken weeks), the liberation of Zuid-Beveland and Walcheren might have cost even more losses among the Allied forces (including Canadian) as well as the civil population and caused more destruction of infrastructure and property. In fact, the escape of the 15th German Army to North Brabant and its contribution to the German defences at the Brabant Line and, later on, during and after Operation Market Garden, helped to slow down Montgomery’s plan for a break-through across the Rhine on Dutch territory.

Various priorities

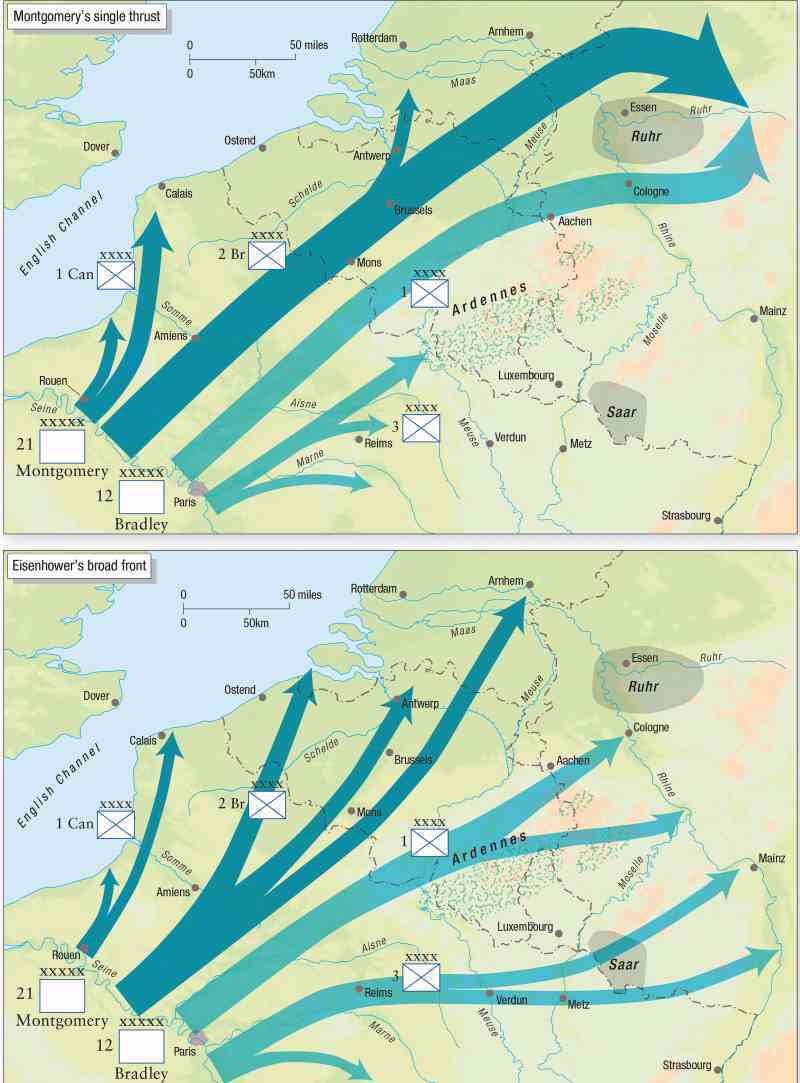

After the liberation of Antwerp the 21st British Army Group faced a set of three tasks. Firstly, the Channel ports of Boulogne, Calais and Dunkirk – all of them strongly defended Festungen – had to be liberated and this could only be done by the infantry divisions of the 1st Canadian Army.[8] Secondly, the Westerschelde mouth had to be occupied in order to open up the approaches to Antwerp. Thirdly, the Brabant Line had to be attacked with the aim of securing the area east of Antwerp. The question was how Montgomery,[9] then Field Marshal, would position the two Armies under his command to carry out these multiple tasks. He considered the first two tasks to be the responsibility of the 1st Canadian Army, commanded by Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar. Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey’s 2nd British Army had to cross the Brabant Line and lead the attack towards the German border. Perhaps Montgomery was still hoping he could change Eisenhower’s mind. On 23 August and on 4 September the Field Marshal had proposed to Eisenhower to concentrate 40 divisions of the two Army Groups for a ‘single thrust’ attack in the north while holding defensive positions south of the Ardennes. Eisenhower had rejected Montgomery’s proposals as he considered such a concentrated attack to be too risky and contrary to the ‘broad front’ strategy which had been agreed at SHAEF earlier on. According to this strategy Germany would be invaded by a double thrust to encircle the Ruhr area: in the north by the 21st British Army Group and the 1st US Army advancing through the Aachen gap; south of the Ardennes by Lieutenant-General George Patton’s 3rd US Army attacking the Saar area and then onwards in eastern direction[10] (see map 2).

Map 2 The alternate plans of Montgomery and Eisenhower, August 1944

Eisenhower’s rejection of the single thrust strategy was not only based on military considerations. He knew that Bradley and Patton would strongly resist the single thrust in the north. Thus, he would encounter serious arguments with his own commanders; additionally, there would most likely be opposition in the US. The political leadership and public opinion would not understand why the overwhelming part of American combat power had to be concentrated under Montgomery’s command. Eisenhower and Montgomery would continue their personal controversy on the preferred military strategy even after the war.[11] Unfortunately, in the autumn of 1944 the differences of opinion on the priorities of the next phase of the war had severe consequences, in particular for the liberation of the Westerschelde area.

Montgomery’s final attempt

In the meantime Montgomery had started to develop a new plan: airborne landings to capture the bridges across the Waal in Nijmegen and the Rhine in Arnhem, combined with an offensive by the 2nd British Army in that direction. When successful, the Ruhr could be attacked from the area north-east of the Siegfried Line.[12] His initiative received support from the staff of the 1st Allied Airborne Army, still present in England and eager to be involved in what looked like the preparatory operation for the final blow to Germany.[13]

German military lead away British paratroopers as prisoners of war in Arnhem during the failed Market Garden operations. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Operation Market Garden was the outcome of this convergence of interests of Montgomery and the leadership of the 1st Allied Airborne Army.[14] Eisenhower was informed and, when he met with Montgomery on 10 September, the Supreme Commander gave his permission to execute the plan. According to Eisenhower’s own account of the meeting, Montgomery was granted permission on the condition that priority would be given by his 21st Army Group to open up access to Antwerp once Market Garden had been concluded. In his account of the meeting Montgomery points out that this was not mentioned at all, so it remains unclear what happened. In a letter to Montgomery on 20 September the Supreme Commander left no doubt about this priority: ‘My choice of routes for making the all-out offensive into Germany is from the Ruhr to Berlin. A prerequisite from the maintenance viewpoint is the early capture of the approaches to Antwerp so that that flank may be supplied.’[15] This priority would be repeated several times by Eisenhower. Nevertheless, he had concurred with launching Operation Market Garden, the consequence of which was the concentration of the 2nd British Army on the Eindhoven-Nijmegen line. The Operation started on 17 September.

Multitasking the Canadians

On 14 September Montgomery sent a new directive to Crerar, perhaps also in response to the pressure by Eisenhower regarding the Antwerp issue. In Directive M.525 the 1st Canadian Army was given four tasks:[16] to capture the Channel ports of Boulogne, Dunkirk and Calais as soon as possible; to open up the route to the port of Antwerp; to take over the positions of the 2nd British Army in the Antwerp area; and to liberate the western part of North Brabant and to continue towards Rotterdam and the western part of the rest of the Netherlands. With only two relatively weak Army Corps available (see figure 1) Crerar was asked to advance on a front extending from Boulogne to Antwerp.[17] He was facing an impossible set of tasks. The three available infantry divisions (two Canadian, one British) would be needed to conquer the strongly defended Festungen of Boulogne, Dunkirk and Calais. Only the 4th Canadian Armoured Division and the 1st Polish Armoured Division, both of which had arrived around 6-7 September in the Bruges-Ghent area, were available for attacking the Germans in the Westerschelde area. But inundated polders, canals and other water obstacles made an attack by heavy armoured units more or less impossible. These operations could only be carried out by infantry divisions. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division would only arrive in the Bruges area to start offensive operations against the Breskens pocket (on the south shore of the mouth of the Westerschelde) after it had conquered Festung Calais on 1 October. In other words, before early October, the 1st Canadian Army was lacking infantry capacity to start offensive operations to clear the south shore of the Westerschelde mouth.

2nd Canadian Army Corps

2nd Canadian Infantry Division

3rd Canadian Infantry Division

4th Canadian Armoured Division

1st British Army Corps

49th British (West-Riding) Infantry Division

1st Polish Armoured Division

Figure 1 Composition 1st Canadian Army, September 1944

Furthermore, Montgomery’s hope of using the Channel ports for logistical supplies as long as the port of Antwerp was not available proved to be idle.[18] The German defenders had destroyed most of the port facilities of Boulogne and Calais. Dieppe could be used, but its capacity was limited to 6,000 tons daily,[19] whereas Dunkirk remained occupied by German forces until May 1945. The air transport capacity was approximately 2,000 tons of logistic supplies daily, but its full use for that purpose implied that no transport aircraft would be available for airborne operations. Post-war logistics studies confirmed that without the use of the port of Antwerp it would have been impossible to provide the required logistical supplies for the AEF’s attack on Germany, either in a single or in a broad front thrust.[20] Thus, Eisenhower and other AEF Commanders were right when stating that the Allied offensive into Germany was not possible without using the port of Antwerp.

Canadian Army denied flank support

On 16 September the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division started to arrive in Antwerp to replace the 51st (Welsh) Infantry Division, which was deployed further east in support of Operation Market Garden. Preparations began for the attack on the Zuid-Beveland isthmus, but the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division – with its infantry strength reduced to approximately 50 percent – was in need of support on its eastern flank in order to liberate the western part of North Brabant and, thus, to secure the entry point to Zuid-Beveland/Walcheren. On 26 September, the day after Operation Market Garden came to an end, Crerar asked Montgomery for permission to allow the 1st British Army Corps (part of the 1st Canadian Army) to carry out an attack on the line towards Bergen op Zoom in order to encircle the German defences south of the city. Crerar was denied flank support, which was directly related to Montgomery’s command decisions after the end of Operation Market Garden.[21] The corridor from Eindhoven to Nijmegen – 80 kilometres long and 20-25 kilometres wide – now had to be defended against German forces to the west and east. Montgomery gave priority to the east, ordering the 2nd British Army to attack in the direction of the River Meuse. Thus, the west side of the corridor became vulnerable to German counter-attacks. For that reason he ordered the 1st British Army Corps – located east of Antwerp in the area under the responsibilty of the 1st Canadian Army – to advance in the direction of Tilburg and on to Den Bosch, neglecting General Crerar’s request to make the Corps available for the flank support that he deemed necessary.[22] The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division had to attack along the Antwerp-Bergen op Zoom line without flank support needed for encircling the German forces.

Civilians take cover as British soldiers exchange fire with German troops: the 1st British Army Corps advanced in the direction of Tilburg and Den Bosch, denying Crerar the flank support that he deemed necessary. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

The command crisis

In early October the Allied offensive had come to a halt once more. At the Westerschelde the situation remained unchanged with one exception. From 16 to 21 September the 1st Polish Armoured Division liberated the eastern part of Zeelandic Flanders.[23] As a result, the Allies controlled the port of Terneuzen, but the western part (‘the Breskens pocket’) and the northern shore of the Westerschelde were still firmly held by German forces. By early October, the 2nd British Army was making hardly any progress east of the Eindhoven-Nijmegen corridor. The 1st US Army, of which two divisions had temporarily been placed under Montgomery’s command and was also lacking adequate supplies for its attack on the Aachen gap, was grounded just east of Liège. The same applied to Patton’s 3rd US Army near Metz. On 5 October another attempt was made at Eisenhower’s HQ to convince Montgomery of the priority he should give to the operations to open the port of Antwerp. At the meeting, the Allied Naval Commander of the Expeditionary Force, British Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, criticised Montgomery for his lack of action, to which the Field Marshal reacted furiously and informed Eisenhower after the meeting that the Canadian offensive was already underway. Ramsay had no knowledge of land warfare, he added. In the following days Eisenhower would make several attempts to convince Montgomery, but to no avail. On 9 October he sent him a letter, headed by ‘For Field Marshal eyes only’. Eisenhower explained that the whole front had come to a standstill and that, without the use of Antwerp, offensive operations would no longer be possible: ‘I must emphasize that, for all our operations on our entire front from Switzerland to the Channel, I consider Antwerp of first importance, and I believe that the operation to clear up the entrance – requires your personal attention.’[24]

Eisenhower’s attempts at diplomacy remained without result until 13 October, when the SHAEF command crisis reached its peak. The British and American Chiefs-of-Staff, Field Marshal Alan Brooke and General George Marshall, became involved although formally they did not belong to the SHAEF command structure. They considered the option of giving Montgomery a formal order, but Eisenhower apparently wanted to avoid such an unusual step.[25] Instead, he threatened Montgomery to bring the matter to higher authorities if he were to persist.[26] The Field Marshal then gave in. On 16 October he issued Directive M.532, stating that operations to free the port of Antwerp must have ‘complete priority’ over all other offensive operations of the 21st Army Group. The full capacity of the 2nd British Army had to be made available for this purpose. Furthermore, the 1st British Army Corps, consisting of the 49th British (West Riding) Infantry Division and the 1st Polish Armoured Division, was reinforced with the 4th Canadian Armoured Division and the 104th US (Timberwolves) Infantry Division. On 20 October Operation Suitcase was launched to liberate the western part of North Brabant (see map 3). The threat of encirclement for the German defensive positions south of Bergen op Zoom by this flanking operation would lead to the withdrawal of the remaining defenders from the Woensdrecht area. This flank operation brought victory for the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. The Canadians could now secure the entry/exit point to Zuid-Beveland, for which they had been fighting on their own for a period of three weeks in October at the cost of around 400 fatal casualties.

Overview of the Battle of the Westerschelde, October-November 1944. Cartography Erik van Oosten, NIMH

An appraisal

Historians have critised Montgomery for a lack of understanding of the military-strategic priorities in September and early October 1944, as he turned the 2nd British Army east instead of west to secure the approaches to the port of Antwerp. The Australian historian Peter Beale[27] accuses Montgomery of having made ‘great mistakes’ by allowing the 15th German Army to escape from the coast via Vlissingen to strengthen the Brabant Line, by pursuing the capture of the Channel ports – binding the infantry capacity of the 1st Canadian Army needed to attack the Westerschelde area – and by launching Operation Market Garden. The Canadian military historian R.W. Thompson puts the blame for the delay of opening up the sea lane to Antwerp fully on Montgomery.[28] Hans Sakkers, who systematically checked the information from the German command centres in Middelburg and Vlissingen available to the AEF leadership through the ENIGMA decoder, concludes that ‘From the point of view of Bletchley Park Montgomery’s strategic choice was an incomprehensible disappointment.’[29] Anthony Beevor does not even shy away from connecting the World War II events to the United Kingdom of today: ‘In fact one could argue that September 1944 was the origin of that disastrous cliché which lingers on even today about the country punching above its weight.’[30]

Eisenhower (left) and Montgomery (right): historians have critised Montgomery for a lack of understanding of the military-strategic priorities in September and early October 1944. Photo ANP/AFP

Indeed, the Field Marshal’s focus on a rapid breakthrough across the Rhine is very clear from, on the one hand, his proposals for a single thrust attack on Germany and, on the other, his initiative leading to Operation Market Garden in the second half of September 1944 and his idea to invade Germany with a 20-plus division strong force. One could argue that Montgomery caused a double delay for the Westerschelde Battle: firstly, in mid-September by launching Operation Market Garden, which was binding the whole 2nd British Army to the central and eastern part of North Brabant; secondly, in late September by directing the 2nd British Army in eastern direction to liberate the area between the Eindhoven-Nijmegen corridor and the River Meuse while refusing the 1st Canadian Army Commander’s request for a flank operation west of the corridor. Why Montgomery was so persistent is food for thought for psychologists. Factors often mentioned are: his ‘El Alamein hero’ reputation, his own ambition, his solistic character, the support of Prime Minister Churchill and his aversion of US commanders. Perhaps one could argue that Montgomery’s mind was locked in a ‘tunnel vision’: he was absolutely convinced that his approach to ending the war with Germany as quickly as possible was the best strategy while neglecting or downscaling the risks of a concentrated attack as well as the problem of logistical supply to sustain such an all-out offensive. Even Montgomery’s most loyal servant, his Chief-of-Staff Lieutenant-General Sir Francis de Guingand, stated: ‘My conclusion is, therefore, that Eisenhower was right when in August he decided that he could not concentrate sufficient administrative resources to allow one strong thrust deep into Germany north of the Rhine with the hope of decisive success.’[31]

Montgomery would never admit that his strategy for a concentrated attack could not have been realised in the autumn of 1944 without the use of the port of Antwerp. However, in his memoires published in 1958 he admitted guilt with regard to the priority issue: ‘And here I must admit a bad mistake on my part – I underestimated the difficulties of opening up the approaches to Antwerp so that we could get the free use of that port. I reckoned that the Canadian Army could do it while we were going for the Ruhr. I was wrong.’[32]

Conclusion

The case of the opening up of the Westerschelde waterway shows how a lack of unity at the military-strategic level can influence the course of a military campaign. However, it is too simple to put all the blame on Montgomery. His 21st Army Group was tasked not only with opening up the approaches to Antwerp, but also with occupying the territory east of Antwerp in order to secure the city from German counter-attacks (in December 1944 the strategic objective of the German Army’s Ardennes offensive was to recapture Antwerp). On top of that Eisenhower granted permission for Operation Market Garden, which also delayed the 2nd British Army’s involvement in operations in support of liberating the Westerschelde area. Despite the fact that he had been appointed Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, Eisenhower in reality was more a primus inter pares. He had to keep the commanders together in one team, but it could only be done at the price of making concessions to them, in particular to Montgomery as he was not American and had the support of Churchill, the British press and the British public. From the point of military effectiveness, Eisenhower could also be blamed for the delay in opening up the approaches to Antwerp, but blaming is easy in hindsight. In the heat of the campaign in the autumn of 1944 Eisenhower’s most important consideration was to prevent a further escalation of what had already become a serious command crisis. He succeeded in that effort, but at the cost of sacrificing an early liberation of the Westerschelde area and, therefore, delaying the use of the port of Antwerp which was so much needed for supplying the Allied forces for the attack on the German homeland.

* Dick Zandee is a historian with a special interest in World War II. The author is grateful to Christ Klep and Lt-col. (Ret.) Wouter Hagemeijer for their valuable comments on the text.

[1] The operational level will be the focus of the second article, to be published in Militaire Spectator No. 11-2019).

[2] Also known as the ‘Red Ball Highways’, mentioned after red ball markers placed along the priority routes.

[3] Two artificial Mulberry Harbours had been constructed on the Normandy beaches, one of which had been damaged during a storm in mid-June. The only available port was Cherbourg, but it was located even further away from the front lines and had limited capacity.

[4] Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe (First Published 1948, Melbourne-London-Toronto) p. 333.

[5] Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW).

[6] See box 1 for a further explanation.

[7] Major-General Sir Francis De Guingand, Operation Victory (First published 1948, London) p. 331.

[8] Le Havre was liberated on 10 September after seven days of bombing, causing the death of 2,053 citizens. Before surrendering the Germans had destroyed the port facilities almost completely.

[9] On 1 September the British Prime Minister and Minister of Defence Winston Churchill had promoted Montgomery to Field Marshal. He therefore held a military rank which was higher than his Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower. On the same day the command of all Allied land forces was transferred from Montgomery to Eisenhower. Despite the fact that this transfer of command was in line with decisions taken earlier, Montgomery would continue to argue that he should command all of AEF’s land forces. Tensions among the AEF’s top commanders, which had already worsened during the Normandy campaign, increased further, also fuelled by the American and British press.

[10] Furthermore, the 6th US Army Group landed in southern France in mid-August, and, after heading north, would attack the Alsace-Lorraine in order to invade the southern part of Germany. The 6th US Army Group consisted of the 7th US Army and the 1st French Army.

[11] In his Crusade in Europe published in 1948 Eisenhower stated that Montgomery, in the light of how the attack on Germany had taken place, should admit that his single thrust had been wrong. In his memoirs, published ten years later, Montgomery continued to argue that the war had been unnecessarily extended due to the spread of forces and logistics along a broad front.

[12] Called Westwall by the Germans: the defensive line west of the River Rhine on German territory, from the German-Dutch border near Wesel to Aachen.

[13] The 1st Allied Airborne Army, commanded by the American Lieutenant-General Lewis Brereton, consisted of three American and two British Airborne Divisions, the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division and the Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. Several times plans were drawn up for airborne landings during the break-out campaign after the Normandy battle: for example near Lille, near Brussels and near Liège. On all occasions plans were cancelled as the AEF’s armoured divisions had already reached the strategic objectives before the envisaged day of the landings.

[14] In the original plan only one British Airborne Division plus the Polish Independent Parachute Brigade would be used in Operation Comet. After Lieutenant-General Brereton made two US Airborne Divisions available, the plan was adapted and the Operation renamed Market Garden.

[15] The Memoirs of Field Marshal Montgomery (First published in Great Britain, 1958) p. 280. ‘Maintenance’ is the term used for logistical supplies.

[16] Directive M.525 is fully quoted in Montgomery’s Memoirs.

[17] In Directive M.525 Montgomery stated that tactical air power and strategic bombing capabilities as well as airborne troops would be made available. The latter never materialised as Brereton considered landings in Zeeland with its waterways, canals and inundated polders too risky, also taking into account the German air defence capabilities.

[18] Montgomery’s original estimate was that the Channel ports of Dieppe, Boulogne, Dunkirk and Calais plus a 3,000 ton capacity of Le Havre and 1,000 ton by airlift could fill the needs of a spearhead attack by 20 divisions (the full 2nd British Army and the 1st US Army plus three airborne divisions) – a reduced force compared to his original proposal as it was clear that Eisenhower was sticking to the broad front strategy. Thus, in Montgomery’s view the use of the port of Antwerp was not an absolute requirement. A note on this was written in the 21st Army Group’s report of 9 September. See: Charles Perry Stacey, The Victory Campaign. The Operations in North-West Europe 1944-1945 (Volume III) (Published by Authority of the Minister of National Defence, Canada, 1960) p. 310.

[19] Dieppe had been liberated on 1 September. The Germans had not succeeded in destroying the port facilitities completely. As of 7 September the port could be used, but its full capacity (6,000 tons) was not available before the end of the same month.

[20] E.g.: Roland R. Rupperthal, Logistics and the Broad-Front Strategy (Center of Military History, United States Army, 1990); Norman R. Denny, Seduction in combat. Losing sight of logistics after D-Day (Knoxville, University of Tennessee, 1989). Rupperthal refers to 12th Army Group calculations that 19,000 tons daily were needed in the first half of October for a 22-division strong offensive; by early November 23,000 tons would be needed to supply a 28-division strong force. In reality, 8,000 to 10,000 tons per day were reaching the forward zone in September and prospects for October were even worse.

[21] The strategic objective of Operation Market Garden was not the bridge in Arnhem. The bridge was just the means to the envisaged end: the occupation of the airfield of Deelen (where the 52nd Infantry Division would be flown in) and to reach the Zuiderzee (now IJsselmeer) in order to cut off the western part of the Netherlands from Germany.

[22] Due to strong German defence operations this attack towards Tilburg would fail.

[23] The terrain in eastern Zeelandic Flanders was better accessable to tank formations. Furthermore, the Germans defended the area with relatively weak forces as the available infantry had to be concentrated in the Breskens pocket.

[24] David G. Chandler, (Ed.) The papers of Dwight David Eisenhower. The war years, (Baltimore & London, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1970) Volume IV, p. 2215. In Montgomery’s Memoirs, p. 283, the quote ends after ‘first importance’. The reference to requiring his personal attention is missing.

[25] Formal military orders were not issued by SHAEF. The Army Groups themselves were given responsibility for the conduct of the operations to reach the strategic objectives set by SHAEF.

[26] Chandler, The papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, Volume IV, pp. 2221-2225.

[27] Peter Beale, The Great Mistakes. The battle for Antwerp and the Beveland Pensinsula, September 1944 (Trupp Stroud Gloucestershire, Sutton Publishing, 2004).

[28] R.W. Thompson, The eighty-five days. The story of the Battle of the Scheldt (London, Hutchinson, 1957).

[29] Bletchley Park hosted the ENIGMA decoding centre. Hans Sakkers, Enigma en de strijd om de Westerschelde. Het falen van de geallieerde opmars in september 1944 (Soesterberg, Aspekt, 2011) p. 289 (translation into English by Dick Zandee).

[30] Anthony Beevor, Arnhem. The battle for the bridges, 1944 (New York, Viking, 2018).

[31] De Guingand, p. 330.

[32] Montgomery, p. 297.