The General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, commonly known as the Dayton Accords, was signed on November 21, 1995 by Slobodan Milošević, President of the Republic of Serbia, Franjo Tudjman, President of Croatia, and Alija Izetbegović, President of the then Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The agreement envisioned deployment of an Implementation Force (IFOR) ‘for a period of approximately one year.’[1] This article takes a retrospective look after 25 years at the cause of this protracted stalemate in Bosnia-Herzegovina (hereafter Bosnia, or BiH) and the security issues that have resulted.

Michael Dziedzic, Col, U.S. Air Force (Ret.)*

Bosnia has been unable to surmount embedded political instability, to advance toward Euro-Atlantic integration, or provide anything more than a semblance of democratic governance for its citizens in the 25 years that have transpired since signing of the Dayton Accords. This is primarily the result of misdiagnosis of the conflict as resulting exclusively from ‘ancient ethnic hatreds’ while failing to recognize until far too late the role that parallel power structures in each of Bosnia’s ethnic communities played in instigating the conflict, collaborating to profit from it economically and politically, and subsequently paralyzing Dayton’s implementation.[2] Inter-ethnic conflict and grievance that marked the conflict in the 1990s have in the post-Dayton era been leveraged to mask corruption, nepotism, and other forms of state capture, using parallel power structures to perpetuate political control. This article describes the composition of the parallel power structures in each of Bosnia’s ethnic communities, the security threats they have posed, the degree to which each has been dealt with, the implications for the way forward in Bosnia, and the lessons that should be learned from the Bosnian experience for future international peace and stability operations.

Frozen chicken reveals the fallacy in conventional conflict diagnosis

The author was assigned to IFOR headquarters in Sarajevo in 1996 and took advantage of his half-day off duty one Sunday afternoon to join a tour offered by the command’s Serb and Bosniak interpreters. The last stop was a large hole in the ground adjacent to the Sarajevo airport. The interpreters explained this was the entrance of a tunnel that ran under the airport that had provided the besieged city its only lifeline for smuggling in food and essential supplies. They described a battle in which they had both participated involving the Serbs raining down artillery fire on the Bosniaks from their mountainous high ground overlooking Sarajevo, inflicting many casualties. The severely wounded needed urgent medical care that could only be obtained by evacuating them through the tunnel. After the injured arrived at the tunnel entrance, they were told by the Bosniak mafia controlling it that they would have to wait for a couple of hours. Frantically, the soldiers demanded to know why. They were told the tunnel had been rented by the Bosnian Serb mafia to import a shipment of frozen chicken which everyone knew would be sold at inflated prices with the proceeds being divided between them.[3]

This was an epiphany. Like virtually everyone else, the author had presumed the cause of the conflict was ‘ancient ethnic hatreds.’ That a shipment of frozen chicken could take priority over the lives of Bosniak soldiers for the mutual profit of the Bosniak and Serb mafias called this conventional diagnosis into profound doubt. It would take the international community several years after the Dayton Accords were signed to recognize and begin to respond to the insidious driver of conflict that parallel power structures constituted in each of Bosnia’s ethnic communities.[4]

Bosnia’s parallel power structures

Bosnia’s parallel power structures[5] originated in the nomenklatura system that had formed the basis of Josip Tito’s Yugoslav regime. When Bosnia fragmented into three ethno-nationalist entities (i.e., Serbs created the Republika Srpska (RS) under Radovan Karadžić and the Serb Democratic Party (SDS), Croats formed the Herzegovinian Croat Community of Herceg-Bosna (a branch of Croatian President Franjo Tudjman’s Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ)), and the Bosniaks coalesced with some Serb and Croat leaders under the control of Alija Izetobegovic’s Party of Democratic Action), the root cause of violent conflict was a grab for power and wealth in Yugoslavia’s crumbling socialist system. As Gerard Toal and Carl Dahlman articulate: ‘Nationalist political parties and local elites took power across Bosnia and turned local municipal resources and industrial infrastructure into personal fiefdoms for asset stripping and corrupt privatization schemes. With the establishment of entity- and state-level institutions, political parties have rewarded supporters with favourable business deals, choice appointments, and rigged contracts…Closely tied to nationalist parties, this business class acquired economic power through political means and keeps it through political manipulations and the power of ethnic patronage.’[6]

In each case, the illicit structures that originated in the Tito regime, prosecuted and profited from the conflict, and were reinforced by international sanctions, emerged from the conflict as the inheritors of power in their respective ethnic communities.

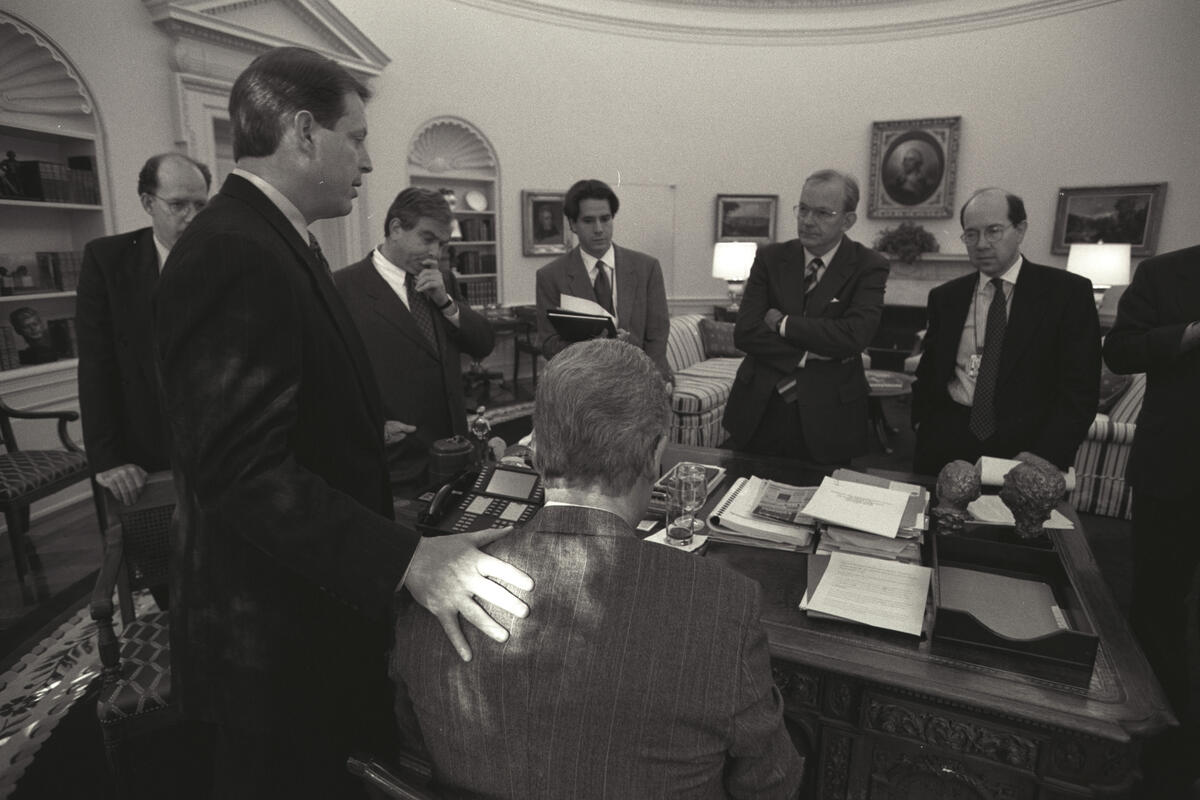

US President Bill Clinton and his advisors discuss remarks announcing the Bosnia-Herzegovina Peace Agreement. Photo William J. Clinton Presidential Library

The term ‘parallel’ is used because many of the most salient relationships are not based on occupying formal governmental positions of power. There is a conflation of formal governance with parallel and informal economic, political, and security interests, much of which is extra-legal. These power centres are parallel to government and are embedded in it through state capture. A study published by the U.S. Army’s Peacekeeping Institute in 2000 documented how the three ethno-nationalist political structures thwarted implementation of Dayton by relying on ‘formal political party structures as well as extra-legal security services (secret intelligence, police, and paramilitary) and transnational criminal syndicates to sustain themselves in power. These ‘unholy alliances’ maintain their hegemony through a monopoly of violence and control over patronage.’[7] Bosnia’s three parallel power structures collaborated to subvert the legal system, including by outsourcing assassination of honest officials to criminal affiliates in another ethnic community and by thwarting prosecutions that might threaten maintenance of their political and economic power by bribing or threatening judicial and police authorities.[8]

The key defining characteristics of Bosnia’s parallel power structures are the following:

- Revenue essential for maintenance of these structures is derived from corrupt or criminal transactions, some of which derive from external sources. Each ethno-nationalist government controls state-owned enterprises that are exploited to generate revenue for their mercenary purposes.

- Power is exercised via informal/parallel structures as well as formal positions.

- Hegemony is maintained through control over patronage as well as through the capacity to eliminate rivals with impunity and subvert the rule of law.

The Dayton Accords provided no explicit authority or capability to deal with parallel power structures.[9] Although IFOR enjoyed a robust mandate, it was focused exclusively on Bosnia’s formal military forces. Owing to the failure to properly assess the spoiler threat from Bosnia’s parallel power structures, international police arrived unarmed and were empowered merely to mentor, monitor, and train Bosnian police. Other components of the legal system were ignored entirely. Neither the UN nor IFOR had a capability to respond to ‘rent-a-mobs’ that were recurrently used to obstruct implementation of the Dayton Accords. This created a public security gap that was eventually addressed in late 1998 by the deployment of a Multinational Specialized Unit (MSU) with a crowd and riot control capability to the Stabilization Force (SFOR), IFOR’s successor. The Office of the High Representative, in spite of its lofty title, was relegated solely to coordinating civilian activities and, according to Dayton, ‘shall have no authority over the IFOR.’[10] International oversight of the three intelligence services was completely overlooked, allowing them to continue directing criminal relationships used by political elites to protect their wartime gains and clandestinely subvert the peace process. Eventually, SFOR recognized that the centre of gravity for stabilizing the conflict was the parallel power structures in each ethnic community.

The Croatian Third Entity Movement

Composition

The Third Entity Movement[11] (hereafter the Movement) was the aspiration of Croatian President Franjo Tudjman.[12] During the 1990s he tried to divide Bosnia between Serbia and Croatia, pursuing this ambition until his death in 1999. The clandestine elements of this parallel power structure included a nexus between the Croatian Intelligence Service and its counterpart in Herzeg-Bosna. There was also a stay-behind unit of the Croatian Army that was converted into the Monitor M Company to avoid complying with the Dayton requirement that all Bosnian Croat military units be placed under Bosnian Federation command.

The Movement had a paramilitary criminal capacity: the Convict Battalion that perpetrated acts of ethnic cleansing during the conflict and the Renner Transport Company that acted as cover for arms trafficking during the conflict and subsequently perpetrated violent confrontations against Muslim returnees. The primary source of illicit revenue for the Movement stemmed from Tudjman’s diversion of proceeds from the sale of Croatian state assets into the Hercegovacka Bank in Mostar that had been established by the Monitor M Company. From 1998-2000, $180 million a year was channeled into the bank. This huge slush fund was used in 1998 to elect a Tudjman crony, Ante Jelavic, as the Bosnian Croat member of the state-level tri-presidency.

Nature of the security threat

The aim of the Movement was to create a Bosnian Croat entity (Herzeg-Bosna) co-equal with the Republika Srpska and the Bosniak-Croat Federation. This would have been a potentially irreversible step toward dissolving the Bosniak-Croat Federation, a cornerstone of Dayton,[13] and unification with Croatia, rendering the Bosniak rump state unviable. The result would undoubtedly have been a return to conflict.

How this security threat has been addressed

The security consequences associated with this parallel power structure are distinguished by the success of the strategy that was implemented between 1999-2001. First the authorities and means had to be authorized to mount an effective strategy. Dayton’s most crippling defect was the inability of the High Representative to act in response to obstruction by the leadership of all three ethno-nationalist factions. At a 1997 meeting in Bonn, the Peace Implementation Council conferred on the High Representative the ‘Bonn Powers’ to make ‘binding decisions…on…interim measures to take effect when parties are unable to reach agreement…’ and ‘…actions against persons holding public office…who are found to be in violation of…the Peace Agreement…’[14] To overcome the public security gap, NATO deployed the Multinational Specialized Unit in 1999 to provide the critically lacking crowd and riot control capability for dealing with the ‘rent-a-mob’ phenomenon that had repeatedly thwarted the return of refugees and displaced persons. Once these authorities and the means to implement them were in place, the military and civilian components of the international community carefully coordinated a sequence of more than a dozen intelligence-led operations among themselves and trusted members of the Bosnian community. The most prominent of these operations was Operation Westar by SFOR, which seized documents in a Bosnian Croat police station in west Mostar that served as the hub for intelligence activities against SFOR and other prominent members of the international community.[15] This operation could not have been conducted successfully without the surveillance and crowd and riot control capabilities provided by the MSU.

IFOR’s successor, the Stabilization Force (SFOR), eventually recognized the importance of the parallel power structures. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Operation Westar led to the discovery of the Achilles heel of this parallel power structure: the Herzegovacka Bank and the flow of illicit revenues from Croatia. With support from SFOR’s MSU and the Federation Ministry of Interior and Financial Police, the High Representative mounted an operation to take control of the bank, seizing sufficient evidence to mount twenty criminal investigations against key components of this parallel power structure. The Movement was dealt a fatal blow. The notion of unification with Croatia is no longer on the table, but more subtle tactics persist to promote autonomous governance for Croats within Bosnia.

The Bosniak Parallel Power Structure

Composition

The Bosniak power structure included the Party of Democratic Action (SDA), the Third World Relief Agency (TWRA), the Benevolence International Foundation (BIF), Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the Sarajevo mafia.

The SDA under Alija Izetbegovic harboured war-time aspirations for an Islamic state that were contrary to the delicate multi-ethnic balancing act enshrined in Dayton.[16] Central to the SDA structure was the Muslim Intelligence Service (MOS) which was comprised of some 300-400 individuals who operated as an underground SDA command-and-control structure within the government. According to Schindler in Unholy Terror, the MOS ‘wielded much of the real power in Sarajevo.’[17]

The TWRA was a Sudan-based ‘humanitarian’ organization created in 1991 headed by Izetbegovic’s long-time friend, Mohammed el-Fatih Hassanein, who claimed in 1994 that ‘Bosnia, at the end, must be Muslim Bosnia.’[18] The Sudan-based TWRA apparently established a close relationship with Osama bin Laden after al-Qaida moved to Sudan just before the war in Bosnia broke out.[19] Between 1992 and 1995 $2.5 billion was unaccounted for by TWRA and the inner core of SDA leaders. Schindler explains: ‘…$2.5 billion had been laundered and distributed by a group of Bosnian Muslim wartime leaders who formed an illegal, isolated ruling oligarchy, comprising three to four hundred ‘reliable’ people in the military commands, the diplomatic service, and government agencies, the SDA, a private party intelligence service, and a number of religious dignitaries.’[20] The ‘private party intelligence service’ referenced was the Muslim Intelligence Service.[21] Given the high-level SDA membership in the MOS, it is likely it functioned as a covert, parallel command-and-control function to ensure that the money distributed by TWRA achieved its intended ideological purpose.

According to Evan Kohlmann, al-Qaida’s primary purpose in going to Bosnia was to serve as a springboard for terrorist attacks in Europe and the United States rather than to assist Bosnia’s Muslims. To achieve this strategic objective, al-Qaida put together an international funding network of Muslim businessmen and banks, liaised with Islamic non-governmental organizations through its own Benevolence International Foundation (BIF), and created training camps for its own mujahedeen fighters imported to Bosnia through the TWRA.[22] The BIF had direct ties to the SDA, the MOS, and the Bosnian Agency for Investigation and Documentation (BAID) — the Bosnian intelligence service. BIF’s head, Enaam Arnaout, was a close friend of Nedzad Ugljen, the deputy director of BAID, who was an Iranian asset and founder of the assassination squad called the Larks (Ševe). Schindler reports that ‘BIF’s contacts with top Bosnian Muslim officials were close and continuing.’[23]

In 1995, as the Dayton Agreement came into effect, the TWRA and the SDA established the Foundation for Aiding Bosnian Muslims. Its five-member board included Hasan Čengić, who later served as Bosnian Minister of Defence, and was identical to the TWRA board and the founding members of the Muslim Intelligence Service. TWRA assets, which reportedly amounted to $2.5 billion, were transferred to the Foundation.[24] Čengić transformed the Muslim Intelligence Service network — the SDA’s hidden, parallel party command-and-control structure — into the economic shareholders of the Foundation for Aiding Bosnian Muslims.

During the war Iran sent Revolutionary Guard military and intelligence training personnel to Bosnia and shipped 5,000 tons of war materiel, some two-thirds of the war materiel received by the SDA, utilizing various Islamic humanitarian organizations as cover, with a tacit ‘green light’ from the US out of sympathy for the plight of the Bosniaks.[25] Thousands of Bosniak military personnel underwent training by the Revolutionary Guard.[26] In 1994 Iran opened its embassy in Sarajevo, which became the largest, and ramped up its propaganda efforts to popularize its Shia brand of Islam, to which very few Bosnian Muslims adhered.[27] A 1996 U.S. House International Relations Committee report noted that the relationship between the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS) and the Bosnian Agency for Investigation and Documentation (the Bosnian intelligence service) was ‘extraordinarily close’ and that Iran ‘accelerated its clandestine efforts’, ‘recruiting well-placed agents’, ‘setting up secret networks’, and ‘working to recruit…future terrorists’. The report also noted that BAID, which was under the financial control of Hasan Čengić, reciprocated.[28]

The Iranian embassy in Sarajevo, Bosnia. Iran opened the largest embassy in the city. Bosnia was central to Iran’s objective of penetrating Europe. Photo Milos Pienkowski

Schindler documents that Saudi Arabia propagated its Wahhabi views from the King Fahd mosque in Sarajevo and more than 150 others that it built after the war ‘…leaving secularists and traditionalists alike worried by the heavy-handed, extremist rhetoric propagated by Saudi-inspired preachers and their militant followers.’[29] Schindler offers this pessimistic assessment: ‘Regrettably the Wahhabization of Bosnia had progressed too far under the SDA’s protection to be undone with some deportations and office closings.’[30]

The Bosniak mafia played a role analogous to the Croat Renner Transport Company: smuggling arms, assassination of members of other ethnic communities and of Bosniak political rivals, and profiting from the conflict by collaborating with organized criminal elements in other ethnic communities. After Dayton, they were also used to prevent the return of Serbs and Croats to Bosniak-dominated municipalities.[31]

Nature of the security threat

While the SDA was not in a position to be choosy about where it went for arms and assistance during the conflict, the motivations of the external actors who came to its support were menacing and ominous. Iran and the al-Qaida-affiliated TWRA sought to exploit the conflict in Bosnia to establish a bridgehead for terrorist purposes into Europe and the US. The SDA also harboured aspirations for an Islamic state that was the antithesis of Dayton, as noted above. This objective could best be furthered, however, by maintaining the appearance of cooperation with Dayton and refraining from overt use of violence against it.

In spite of the SDA’s predilection to avoid violence, this did not apply to their fellow-travellers. Bosnia was central to Iran’s objective of penetrating Europe, according to a 1996 report by the House Committee on International Relations.[32] Shortly after 9/11, based on intelligence sources and methods the US was unwilling to disclose, six Algerians were arrested for allegedly planning to bomb the US Embassy.[33] According to the Washington Post, three of the six ‘were working for Muslim NGOs that were fingered for their extremist ties in a CIA report from 1996.’[34] Their case was later dropped for lack of admissible evidence.[35] According to the 9/11 Commission Report, terror-mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, along with three of the hijackers (Nawaf al Hazmi, Salem al Hazmi, and Khalid al Mihdhar), all fought in the Bosnian jihad.[36] In November 2002, the UN Security Council’s Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee listed the Benevolence International Foundation ‘as being associated with Al-Qaida, Usama bin Laden or the Taliban.’ The U.S. Treasury also designated BIF as a financier of terrorism in November 2002.[37] In the Western Balkans, Bosnia and Kosovo are considered to have the highest per capita number of fighters provided to Iraq and Syria, with 260 having departed from Bosnia between 2012-2015.[38]

BIF was apparently responsible for recruiting an SDA secret policeman, Munib Zahiragic, who ‘passed at least several hundred BAID documents to BIF head Arnaout. He shared the information with al-Qaida, which used the top secret files to warn mujahideen of investigations.’[39]

In February 2001 around 100 retired SDA members and military, intelligence, and police officials met to plan the revival of the Patriotic League, a paramilitary organization formed in 1991 at the inception of the war that was separate from the Yugoslav People’s Army.[40] The purpose of the new Patriotic League was to form another parallel institution consisting of a military and a political wing that would fight in a future war alongside the Bosniak portion of the Federation’s military. Considering that the meeting took place after the SDA had been voted out of power for the first time in a decade and was being pressed by the incoming Social Democratic government over its wartime corruption and terrorist ties, this meeting suggests that SDA hardliners had not renounced their militant war aims.[41]

How this security threat has been addressed

In February 1996 IFOR raided a training-school for BAID operatives at Pogorelica run by the Iranian intelligence service.[42] IFOR contended the Iranians were running a covert terrorist school. According to the Pentagon and NATO commanders ‘…there was “clear circumstantial evidence” the group was planning possible attacks on NATO forces.’[43] The Izetbegovic government claimed Pogorelica was a counter-terrorist training-school.[44] Subsequently, the President of Bosnia and Herzegovina, who at the time was a Bosniak, said that ‘The thing in Pogorelica near Fojnica was our big mistake.’[45]

In the post-9/11 era, particularly after the Social Democrats replaced the SDA in power (2000-2002) and Munir Alibabić was head of the recently formed Federation’s Intelligence and Security Service (FOSS), the war-time linkage between the TWRA and the SDA was investigated. This revealed that between 1992-1995 $2.5 billion was unaccounted for by TWRA and SDA leaders, as noted above. The FOSS report concluded that it was TWRA, not the official government in Sarajevo, that ‘controlled all aid that Islamic countries donated to the Bosnian Muslims throughout the war.’[46] Even more ominous from an international terrorism perspective was the discovery that the SDA had issued thousands of passports to foreign fighters without records.

Although IFOR enjoyed a robust mandate, it was focused exclusively on Bosnia’s formal military forces. Photo NATO

In March 2002, Bosnian police raided BIF’s Sarajevo office and discovered ‘…weapons, booby traps, false passports, bomb-making instructions…handwritten letters that Aranout and Osama bin Laden had sent to each other, and documents showing that Arnaout had purchased weaponry to distribute to camps operated by al Qaeda and other mujahideen fighters.’[47] In May 2002, SFOR discovered three secret ammo dumps with 110 tons of ammunition — including mortars, gunpowder, and rockets in excellent condition — in the Bosniak neighbourhood of east Mostar. Press speculation centred on Hasan Čengić’s role in hiding the weapons as the former Federation Defence Minister.[48]

How successful has NATO’s strategy been? In spite of the Dayton requirement that foreign combatants depart, according to Ebi Spahiu, ‘After the war’s end, a few hundred mujahideen remained in Bosnia…’ where they concentrated in isolated communities and were probably joined over the years by other extremists.[49] In 2007 600 unlawfully obtained passports were revoked, suggesting the lower threshold for this threat.[50] Spahiu estimated that two per cent of Bosniaks affiliate with the Salafists/Wahabbists, who, though small in percentage terms and not necessarily inclined to espouse violence, constitute a worrying number of prospective recruits.[51] Matteo Pugliese reports by 2019 ‘…25 people have been sentenced to a total of 47 years in prison for various terrorism-related crimes, including recruitment, incitement and traveling to Syria and Iraq.’[52] He goes on to argue that a substantial percentage of Jihadist fighters from the Balkans have yet to return, creating a substantial threat that they might ‘join the migrant flow and infiltrate the European Union.’[53] In sum, the continued presence of potential terrorists (estimated by the BiH Intelligence and Security Agency (OSA) director at 3,000 in 2010),[54] the extensive linkages between the Iranian intelligence services and Hasan Čengić’s wing of the FOSS (now OSA), and the influence of Saudi Arabian theology (Wahhabism) and money has created an enduring terrorist threat inside the country.[55] As Vlado Azinović concludes, ‘Once a destination country for foreign fighters, Bosnia and Herzegovina is now a country of origin for volunteers fighting wars in distant lands.’[56]

The other issue is the posture of Bosniak authorities toward the residual terrorist threat in their midst. Other than the neutralization of the BIF, there is little evidence that the shadow power structure affiliated with the MOS has dissipated. It also remains to be seen whether the SDA has forsaken Alija Izetbegovic’s aspiration articulated in his Islamic Declaration to eventually establish a Muslim majority state. Promisingly, after 9/11, Bosnian officials took assertive action to banish remaining El Mujahid elements by revoking their visas and shuttering Islamic charities that had been fronts for their financing.[57] Bosnian authorities are also actively arresting and prosecuting fighters returning from Iraq, Libya, and Syria.[58]

Reform of Bosnia’s competing intelligence services began to gain traction with the High Representative’s decision establishing the Expert Commission on Intelligence Reform. The Commission drafted a law creating the state-level OSA that was passed by the BiH Parliament in 2004. The first OSA Director, Almir Dzuvo, and his Director of Operations, a Bosnian Serb, both played major, constructive roles within the Commission and were seen to be politically ‘non-aligned’ by nationalist parties. After OSA’s establishment, a Norwegian-funded team of western intelligence experts took the lead in developing OSA’s institutional capabilities by providing training courses/mentoring and creating an OSA training centre. By 2006, OSA was regarded as a much more reliable and professional partner for NATO on domestic and regional counterterrorism matters and investigation of war crimes suspects.[59] After Bakir Izetbegović solidified his control over the SDA in 2010, however, ‘The SDA increasingly began to affiliate itself directly with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s AK Party.’[60] Over the strong objections of western supporters of Dayton, the SDA replaced Dzuvo with Osman Mehmedagić whose political fealty the SDA could count on. According to a practitioner engaged in the BiH intelligence reform process ‘Dodik couldn’t have been happier. One of the few successful BiH state institutions eating itself up from within.’[61] The bottom line, according to Vlado Azinović, is that: ‘...cooperation among security agencies in BiH is limited...The appointment of senior security sector officials in BiH...is inescapably political; and appointees are thus guided by the political interests of their sponsors rather than the security interests of the citizenry. This dynamic clearly negatively impacts the fight against terrorism.’[62]

Parallel power structure in the Republika Srpska

Composition

The core components of the RS power structure include the political figurehead (not always the formal head of government),[63] the security apparatus (military, police, and intelligence services), and paramilitary/organized crime groups, abetted by Russia. All of these are lubricated by informal/illicit economic exchange relationships.

Russian President Vladimir Putin attends a Night Wolves motorcycle club event. Russia has become a more assertive presence in the Republika Srpska, supporting paramilitary groups like the Night Wolves. Photo Kremlin

It is especially difficult to disentangle the power structure of the RS since there is considerable overlap within this ‘unholy alliance’. According to the International Crisis Group, ‘The RS (police) force is filled with war criminals and actively supports persons indicted by the (ICTY)…Some criminals cooperate with or act under the protection of the police…’ (brackets added).[64] A report by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime states that ‘Some paramilitary fighters even became members of the state security units, further reinforcing the link between the government and the underworld.’[65] Perhaps thousands of paramilitary/criminals not integrated into the formal security apparatus were retained on an off-the-record payroll, as was Bosnian Serb General Ratko Mladić, the ICTY indicted war criminal who continued surreptitiously on the RS payroll until 2002.[66] Revenue to maintain this clandestine protection network — with the preponderance siphoned off by those at the top — derives from state-owned enterprises and ‘sophisticated schemes to embezzle government funds, for example in banking and public utilities.’[67] A 2003 report by the EU Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) cites RS advisor for economic issues, Milica Bisic, as stating that ‘according to official estimates the RS budget annually loses DM300-DM500 million [$180-$300 million], which is one half of its annual value’ (Brackets added).[68] This is due to corruption in the form of evasion of customs fees and taxes.[69] According to an investigative reporter, ‘A number of RS companies have been declared “strategic”…because they are making profit, which is used to finance the political parties that control them…’[70] In recent years, Russia has become a more assertive presence in the RS, supporting paramilitary groups like the Night Wolves motorcycle club — extremist agitators who have also been used for cross-border interventions in Ukraine.[71]

Nature of the security threat

Radovan Karadžić served as President of the RS during the Bosnian conflict. After the Dayton Accords were signed and he was indicted as a war criminal by ICTY, his quintessential purpose was to maximize RS autonomy and protect himself and other indicted war criminals (e.g., General Ratko Mladić) from arrest. Pursuant to this, even after he ceased to wield formal power as an elected official, he exploited the informal power structures of the RS to obstruct implementation of Dayton through use of rent-a-mobs and occasional violence.

In 1998 Milorad Dodik, founder of the Party of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD), emerged as a prominent competitor for power in the RS when he was elected Prime Minister as part of Biljana Plavšić’s Unity coalition. At that point, he projected an image as a moderate alternative to Karadžić and the SDS and accordingly was supported by the US and European Union.[72] However, since being re-elected as RS Prime Minister (2006–2010), then as President (2010–2018), and in 2018 as a member of Bosnia’s three-person Presidency, Dodik has governed as a nationalist advocating self-determination and separatist policies for Bosnian Serbs.[73] He has threatened to conduct referenda on independence and secession from BiH as well as on the legitimacy of Bosnia-Herzegovina’s state-level institutions, such as the prosecutorial and judicial system and the Army.

In 2011 Dodik planned to conduct a referendum ‘to reflect what he says is a widespread rejection of Bosnia's federal institutions, especially the war crimes court…’[74] According to the Center for Investigative Journalism, ‘It’s a smokescreen to stop the probes into his business dealings.’[75] In 2012, Dodik called for the abolition of Bosnia’s army, the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina (AFBiH).[76] In February 2020 he again threatened to secede in reaction to a ruling by Bosnia’s Constitutional Court, which includes three international judges, that had awarded unused RS agricultural land to the central Bosnian state.[77] High Representative Valentin Inzko (Austria) said ‘Secession would mean crossing a red line’, but since the Entities have no right to secede under Dayton he also said ‘he was convinced a referendum on secession would not take place.’[78]

Dodik’s calls for both secession and elimination of the AFBiH oblige an assessment of the role that Bosnia’s security forces might play if he were to act on these threats. On the one hand, the most salient institution-building accomplishment that has resulted from the Dayton process is the merging of the Army of Republika Srpska into the AFBiH in 2006.[79] The force has acquitted itself commendably by sending contingents to support the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan (beginning even before the AFBiH was formally created in 2006) and in providing effective disaster assistance during the 2014 floods. If faced with an existential threat like RS secession, however, Kurt Bassuener concludes that ‘…it would collapse along its ethnic fault lines. The AFBiH cannot but reflect the politically-driven polarization which dominates the political arena in BiH...The structure of the force, with ethnicized infantry battalions, lends itself to disintegration under pressure, absent external stabilization of the overall political environment.’[80] In contrast to the Army, efforts to unify the police forces of the Federation and RS were a total failure. According to the Foreign Policy Research Institute, ‘In order to prepare for a future separation of the RS from Bosnia, President Dodik is arming and equipping RS police and related security forces with military-grade weaponry and training.’[81]

Although secession by Dodik may not be likely, such an action would precipitate a seriously destabilizing international crisis. Perhaps the gravest threat from Dodik’s machinations, however, especially in connivance with his Bosnian Croat counterpart Dragan Čović, is state collapse. Kurt Basseuner provides this warning in his Congressional testimony in 2019: ‘...the alliance between Dodik and HDZ BiH leader Dragan Čović has steadily subverted all the progress achieved in the first decade after the war (at massive taxpayer cost) with the aim of effectively carving out more secure feudal fiefdoms of absolute control, ultimately leading to state collapse – which could not be peaceful under any foreseeable circumstances…Absent the external enforcement, pressure, and deterrence that attended its first decade with American focus and muscle, it defaults to precisely what we see today: slow but inexorable and accelerating dissolution of the state, attended with ever more open and shameless corruption, abuse of power, and generation of fear.’[82]

Former president of Republika Srpska Milorad Dodik kisses the flag of Republika Srpska. Photo Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Serbia

How this security threat has been addressed

Both Karadžić and Mladić, along with some 50 other war criminals from the RS, were convicted or died while on trial.[83] The illicit and subterranean networks that perpetuated them in power have been usurped by Dodik. Today he persists in opposing Dayton and insisting on maximal autonomy for the RS. For obstructing Dayton, he was denied access to any assets in the US and use of the US banking system for any transactions by the Treasury Department in 2017.[84] Perhaps the most compelling reason Dodik is not likely to act on his threat to secede, however, is that the US, along with other NATO powers, would view such an action as a reckless step toward renewed conflict and would immediately intervene assertively to avert it.[85] He is also constrained because if he actually seceded he would risk being defeated. Official Belgrade is at best ambivalent over the prospect of seeing the RS join Serbia, so in order to survive, Dodik would have to become a vassal of the Kremlin.

Implications for the way forward in Bosnia

The Dayton Peace Accords failed to recognize or anticipate the pernicious and destructive impact that Bosnia’s ethno-nationalist parallel power structures would have on efforts to stabilize Bosnia. Thus, the ‘golden hour’ at the inception of the mission, when prospects for success were greatest, was irretrievably lost. Compounding this, the Accords contained provisions that encumbered the mission’s ability to mount an effective response (e.g., the intentional lack of coordination between military and civilian efforts, unarmed UN police, and the failure to address the judicial system at all). This thwarted essential reforms to dismantle parallel power structures, establish the rule of law, and create viable state-level institutions to combat corruption, organized crime, and terrorism. In his 2019 Congressional testimony, Kurt Bassuener encapsulated the stultifying status quo: ‘Bluntly put, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s political elite constitutes a political-business-organized crime-media nexus which can currently a) keep what they stole, b) remain positioned to keep stealing, and remain unaccountable politically and legally…While the ethnic political elites may compete for relative territorial and economic dominance, configuration of the state, or whether there should even be a state at all, they can all agree on those basic elements of BiH’s political operating system.’[86]

The bottom line is that Bosnia remains a dysfunctional state because criminalized power brokers persist in each ethnic community. They share a common purpose in preventing the rule of law from taking root, since that would threaten their access to power and illicit sources of wealth. The defeat of the Third Entity Movement’s aspirations for unification of Herzeg-Bosna with Croatia constituted only one out of three, which was not sufficient to alter this reality.

The institutions established to investigate and prosecute criminal misconduct — most notably the High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council and State Investigation and Protection Agency — are under-resourced and lack conflict of interest mechanisms to ensure compliance with the law. In 2019, the Council of Europe’s anti-corruption monitoring body, GRECO, reported the existence of chronic ‘…problems related to corruption such as public procurement, corruption in the judiciary, but also the lack of a systemic law on conflicts of interest at the state level. Bosnia and Herzegovina has failed to comply with any of the 15 recommendations made by…GRECO.’[87]

Although the Dayton Agreement remains the linchpin of Bosnia’s security, the pathway to self-sustaining peace has been strewn with obstacles in the post-war period. The country’s Euro-Atlantic integration progress has languished in the face of fundamental disagreement between ethnic leaders on Bosnia’s security architecture in wider Europe and a political penchant to rely on short-term patron-like arrangements with international powers, including Moscow and Ankara. Unforeseen external threats such as migration and Covid-19 have also emerged. This has strained domestic political cohesion and altered the political calculus in Europe in evaluating how and when to promote integration of the Western Balkans into the EU. Endemic political conflict and corruption, abetted by collusion among ethno-nationalist power structures, have precluded meaningful progress in social and economic reform. This, in turn, has precipitated increasing levels of emigration, especially among the educated youth despairing of opportunity in BiH. The growing propensity to emigrate coupled with a stalled birth rate could present existential security threats to BiH as informal social capital dissipates and economic viability becomes more questionable.

In sum, 25 years after Dayton, the Bosnian conflict is frozen.[88] The culpability of Bosnia’s parallel power structures is evident. The need to engender the rule of law and functional transparency and accountability mechanisms is also obvious; however, the way to unravel this Gordian knot after 25 years is not.[89]

Lessons for future multilateral peace and stability operations

Essential for the success of future NATO peace and stability operations will be developing an assessment methodology that is mutually accepted by its prospective international partners to identify likely spoilers prior to drafting a mandate. The NATO Stability Police Center of Excellence initiated this endeavour in October 2019 in collaboration with the United Nations, European Union, and African Union.[90] Owing to the Covid-19 pandemic, the follow-on workshop had to be delayed until 2021. Among the salient issues for NATO to resolve with its prospective international partners is whether the definition of spoilers should be expanded to include non-violent forms of spoiling such as those experienced in Bosnia: espionage against the mission, grand corruption, and undermining of the legal system so that impunity is guaranteed to those responsible for obstructing the peace process. Gaining international acceptance that non-violent forms of spoiling are a recurrent and incapacitating phenomenon and then developing a spoiler assessment methodology will be essential for avoiding future stalemated missions like Bosnia. This will also be essential for NATO to successfully accomplish timely transitions to follow-on security forces in future hybrid missions.

SFOR in Bosnia and Herzegovina. 25 years after Dayton, the Bosnian conflict is frozen. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Secondly, when the spoiler threat comes in the form of a criminalized or parallel power structure, the initial mandate should empower the mission to resort to a hybrid international and domestic court to prosecute violations of the mandate. The court’s remit should include assassination of political rivals, predation and violence against civilian groups, orchestrated demonstrations to thwart peace implementation (i.e., rent-a-mobs), grand corruption, and espionage against the mission. Actions such as Operation Westar should be mounted as early as possible in the mission to raise costs for illicit activity and establish that the rule of law has primacy because it is backed demonstrably by assertive and effective action to prosecute those responsible. As Bosnia has amply demonstrated, this quintessential tool for spoiler management can only be effectively implemented if it is included in the initial mandate so the mission is empowered to seize the ‘golden hour’ effectively. Thus, it hinges on having an effective spoiler assessment.

Finally, the deployment of the MSU was crucial for closing the public security gap in Bosnia and beginning to counter the destabilizing impact of parallel power structures. According to a U.S. Army Peacekeeping Institute report, ‘SFOR Lessons Learned in Creating a Secure Environment for the Rule of Law’, published in 2000, ‘the MSU was able to resolve 261 of 263 “interventions” without the use of force through a combination of deterrence, dissuasion, and negotiation.’[91] NATO needs to promptly approve the Stability Policing concept and then invest in developing stability policing capabilities for future NATO missions in the form of gendarme-type forces, military police trained to perform stability policing functions, and civilian police capable of operating in a hostile environment. [92]

[1] The General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, initialed in Dayton on November 21, 1995 and signed in Paris on December 14, 1995. See: https://www.osce.org/bih/126173?download=true.

* The author is Adjunct Professor in the George Mason University International Security Masters Program teaching ‘Strategies for Peace and Stability Operations’. I am immensely indebted to Reuf Bajrović, Kurt Bassuener and Valerie Perry for their invaluable insights and suggestions on the final draft of this article. Any errors or omissions are solely my responsibility.

[2] The standard ‘ancient ethnic hatreds’ explanation for the war is challenged by Gerard Toal and Carl Dahlman in Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal. They conclude that the root cause of violent conflict was a grab for power and wealth by political and economic elites in Yugoslavia’s crumbling socialist system. Gerard Toal and Carl T. Dahlman, Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011) 303.

[3] See UN Office on Drugs and Crimes, ‘Crime and its Impact on the Balkans and affected Countries’, March 2008, 51. See: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Balkan_study.pdf. See also Peter Andreas, Blue Helmets and Black Markets: The Business of Survival in the Siege of Sarajevo, (Ithaca, N.Y., Cornell University Press, 2008). See also ‘A Letter about Obstacles Facing the Sarajevo Water project’, Frontline, undated. After George Soros funded the construction of a water system for Sarajevo so citizens didn’t have to expose themselves to sniper fire by seeking water from the river, the Sarajevo government refused to allow it to be used for months. Reading between the lines, the reason was that the Bosniak mafia made money selling water to Sarajevo residents. See: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/cuny/laptop/waterproject.html.

[4] See Daniel Hamilton, Fixing Dayton: A New Deal for Bosnia and Herzegovina (Washington, D.C., Wilson Center, November 2020) 2, 4. ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina has been captured by kleptocratic elites and outside influencers who empower them…These structures entrench an ethnocracy ripe with clientelism that inflames ill-will among the country’s citizens on a daily basis. Corruption is endemic and growing; it has degraded the country’s governance, undermined its democracy, reduced public trust in state institutions, distorted the economy, and attracted dubious financial flows that ripple through the rest of Europe.’ Available at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/fixing-dayton-new-deal-bosnia-and-herzegovina.

[5] Parallel power structures are a type of criminalized power structure that constitutes the predominant spoiler threat for both UN and NATO peace and stability operations. The defining characteristic of a criminal power structure (CPS) ‘...is that ill-gotten wealth plays a decisive role in the ability of a CPS to capture and maintain political power. Violent repression of opposition groups is also typically used to maintain power, supplemented by dispensing patronage to a privileged clientele group. This leads to a zero-sum political economy conducive to conflict, but it may be masked by ethnic or other cleavages in society.’ See the introduction and Bosnia chapters in Michael Dziedzic (ed.), Criminalized Power Structures. The Overlooked Enemies of Peace (Lanham, Rowman and Littlefield, 2016).

[6] Toal and Dahlman, Bosnia Remade, 303.

[7] U.S. Army Peacekeeping Institute, ‘SFOR Lessons Learned in Creating a Secure Environment with Respect for the Rule of Law’, May 2000. See also Hugh Griffiths, ‘Investigation: Will Europe Take on Bosnia’s Mafia?’, Institute for War and Peace Reporting, February 21, 2005. See: https://iwpr.net/global-voices/investigation-will-europe-take-bosnias-mafia. Griffiths notes that several large criminal gangs had evolved into near-oligarchic networks with links to corrupt politicians who, if they needed protection, could call upon the secret police and the mafia.

[8] See also Griffiths, ‘Investigation: Will Europe Take on Bosnia’s Mafia?’.

[9] The authority to remove leaders who obstructed implementation of Dayton and to impose laws when Bosnian authorities refused to act, commonly called the Bonn Powers, was inferred from Annex 10 that deals with the High Representative. See ‘General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Annex 10’, ‘Agreement on Civilian Implementation’.

[10] ‘General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Annex 10’, ‘Agreement on Civilian Implementation’, paragraph 34, 53.

[11] Much of this section is extracted from Michael Dziedzic, ‘NATO Should Promptly Implement Stability Policing: Why and How’, in: Militaire Spectator 189 (2020) (2) 60-2.

[12] Josip Glaurdic, ‘Inside the Serbian War Machine: The Milosevic Telephone Intercepts, 1991–1992’, in: East European Politics & Societies 23 (2009) (1) 86–104.

[13] In the March 1994 Washington Agreement, Croatia and Bosnia agreed to ‘…a federation of Croat and Bosniac majority areas in Bosnia-Herzegovina…’. ‘Washington Agreement’, March 1, 1994. See: https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/file/resources/collections/peace_agreements/washagree_03011994.pdf.

[14] Office of the High Representative, ‘PIC Bonn Conclusions’, December 10, 1997, Section XI High Representative. See: https://web.archive.org/web/20071017204605/http://www.ohr.int/pic/default.asp?content_id=5182.

[15] Other targets of this Croatian and Bosnian Croat intelligence activity were the Office of the High Representative, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and the International Police Task Force. See: NATO, ‘Operation Westar Preliminary Results’, December 17, 1999. See: https://www.nato.int/sfor/sfor-at-work/opwestar/t991216a.htm.

[16] See Alija Izetbegovic, ‘The Islamic Declaration: A Programme for the Islamization of Muslims and the Muslim Peoples’, Sarajevo, 1990, 30, 49. ‘First and foremost of these conclusions is the certainty of the incompatibility of Islam with non-Islamic systems. There can be neither peace nor co-existence between the Islamic religion and non-Islamic social and political institutions.’ And: ‘The Islamic order can only be established in countries where Muslims represent the majority. If this is not the case, the Islamic order is reduced to mere power sharing.’ See: http://www.angelfire.com/dc/mbooks/Alija-Izetbegovic-Islamic-Declaration-1990-Azam-dot-com.pdf; See also Xavier Bougarel, ‘Bosnian Islam since 1990: Cultural Identity or Political Ideology?’, paper presented at the Annual Convention of the Association for the Study of Nationalities, Columbia University (NY), April 15, 1999. See: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/file/index/docid/220516/filename/Bosnian_Islam_Since_1990.pdf. Bougarel describes the objective of the SDA as a ‘“greater Muslim” project: a state composed of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Sandjak, in which Muslims would be the majority, and the Serbs and Croats would be reduced to national minorities.’

[17] John R. Schindler, Unholy Terror: Bosnia, al-Qa’ida, and the Rise of Global Jihad (St. Paul, MN, Zenith Press, 2007) 309.

[18] Evan F. Kohlmann, Al-Qaida’s Jihad in Europe: The Afghan-Bosnian Network (Oxford, Berg Publishers, 2004)

[19] Kohlmann, Al-Qaida’s Jihad in Europe, 45, 217-228; See also John Pomfret, ‘Bosnia's Muslims Dodged Embargo’, Washington Post, September 22, 1996.

[20] Schindler, Unholy Terror, 150.

[21] Ibidem, 150.

[22] Ibidem.

[23] Ibidem, 161.

[24] Ibidem, 161. Schindler calls it a Fund, but the actual name is Foundation.

[25] U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on International Relations, ‘Final Report of the Select Subcommittee to Investigate the United States Role in Iranian Arms Transfers to Croatia and Bosnia’, October 10, 1996, 8-10, 76-7, 85, 164, 167, and 168. See: http://www.archive.org/stream/finalreportofsel00unit/finalreportofsel00unit_djvu.txt.

[26] Ibidem, 175-6.

[27] See Edina Bećirević,’Bosnian and Herzegovina Report’, Extremism Research Council, April 2018, 7. ‘Before that, this reductionist ideology had been unknown to Bosnian Muslims – who have historically followed the Hanafi legal tradition (fiqh) and have practiced an inclusive and...tolerant of other communities, and compatible with liberal Western values...it was not foreseen that the ideology would spread among the Bosnian population even after most of the foreign mujahideen had left the country...’

[28] U.S. House of Representatives, ‘Final Report of the Select Subcommittee’, 176.

[29] Schindler, Unholy Terror, 307. See also Bećirević, ‘Bosnian and Herzegovina Report’, 7. ‘In the harsh light of the terrorist attack of 11 September 2001, media actors in BiH exposed the Saudi High Commission, as well as other organisations that had been hiding behind a veil of humanitarian assistance (including the Benevolence International Foundation, the Global Relief Foundation, the Al- Haramain Foundation, Al Furqan, and Taibah International), as potential sources of extremism and even terrorism. Under pressure from the international community, a number of Gulf-funded (mostly Saudi) organisations were shuttered and the influence of Salafism in BiH was temporarily muted.’

[30] Ibidem.

[31] Author interview with a knowledgeable source.

[32] U.S. House of Representatives, ‘Final Report of the Select Subcommittee’, 8-10, 76-7, 85, 164, 167, and 168.

[33] Craig Whitlock, ‘At Guantanamo, Caught in a Legal Trap: 6 Algerians Languish Despite Foreign Rulings, Dropped Charges’, Washington Post, August 21, 2006, 3.

[34] Marc Perelman, ‘From Sarajevo to Guantanamo: The Strange Case of the Algerian Six’, Mother Jones, December 4, 2007, 7. See: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2007/12/sarajevo-guantanamo-strange-case-algerian-six/.

[35] Perelman, ‘From Sarajevo to Guantanamo’.

[36] ‘The 9/11 Commission Report’, Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, U.S. Government, 58, 147, 155. See: https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

[37] United Nations Security Council, ‘Benevolence International Foundation’, November 19, 2010. See: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/1267/aq_sanctions_list/summaries/entity/benevolence-international-foundation; U.S. Department of Treasury, ‘Treasury Designates Benevolence International Foundation and Related Entities as Financiers of Terrorism’, November 19, 2002. See: https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/po3632.aspx.

[38] Edina Bećirević, Majda Halilović, and Vlado Azinović ‘Literature Review: Radicalization and Violent Extremism in the Western Balkans’, Extremism Research Council, March 2017, 19. See also Vlado Azinović, ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Nexus with Islamist Extremism’, Democratization Policy Council, November 2015, 1. ‘BiH has become a country of origin for mujahideen. The ideological, financial, logistical, and operational engagement of several hundred members of BiH Salafi communities in the war zones in Syria and Iraq has shined a harsh light on this new reality.’

[39] Azinović, ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Nexus with Islamist Extremism’, 244, 289; See also ‘Discover the Networks: Benevolence International Foundation (BIF)’, 6. See: https://www.discoverthenetworks.org/organizations/benevolence-international-foundation-bif/.

[40] Schindler, Unholy Terror, 159. The 2001 meeting took place in the same school in Travnik where the mujahedeen had trained members of the El Mujahid unit comprised of foreign Muslim volunteers that fought alongside the Bosnian Army.

[41] Suzana Mijatovic and Senad Avdic, ‘Reviving the Patriotic League’, Slobodna Bosna, March 27, 2003.

[42] Kohlmann, Al-Qaida’s Jihad in Europe, 173. Ivo Luèiæ, ‘Security and Intelligence Services in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, National Security and the Future, Croatian Institute of History, Updated on October 28, 2015, 94. See: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27202734_Security_and_Intelligence_Services_in_Bosnia_and_Herzegovina.

[43] ‘Potential Terrorism in the Balkans (part 5): US Governmental Accusations and Pogorelica Case’, Balkan Post, May 8, 1996. See: https://www.balkanspost.com/article/583/potential-terrorism-balkans-part-5-us-government-accusations-pogorelica-case.

[44] ‘Potential Terrorism in the Balkans (part 5).

[45] Luèiæ, ‘Security and Intelligence Services in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, 94. See also the next paragraph: ‘In June 1996, two AID operatives and two members of special police forces (the Bosna unit) of the BIH Ministry of Internal Affairs kidnapped, interrogated, tortured, and shot a colleague of theirs, also an AID operative. They finally dropped him in a sewer, but he survived. Today he is allegedly a protected witness of the Hague Tribunal investigating crimes purportedly committed by the special police unit, “Ševe”. This suggests BAID may have attempted to assassinate the person who informed SFOR about the presence of the terrorist training camp in Pogorelica’.

[46] Luèiæ, ‘Security and Intelligence Services in Bosnia and Herzegovina’. BIF’s chief executive officer Enaam Arnaout pled guilty in U.S. Federal Court to racketeering in 2003 and received a ten-year sentence. ‘New Sentence for Charity Director’, The New York Times, February 18, 2006.

[47] ‘Discover the Networks: Benevolence International Foundation (BIF)’, 6. See: https://www.discoverthenetworks.org/organizations/benevolence-international-foundation-bif/.

[48] See SFOR’s original report at http://www.nato.int/sfor/indexinf/139/p03a/t02p03a.htm.

[49] Ebi Spahiu, ‘Islamic Radicalism in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, in: Filip Ejdus and Predrag Jurekovic (eds.), Violent Extremism in the Western Balkans (Vienna: National Defence Academy, 2016) 91. See: https://www.bundesheer.at/wissen-forschung/publikationen/publikation.php?id=940.

[50] Spahiu ‘Islamic Radicalism in Bosnia and Herzegovina’.

[51] Ibidem.

[52] Ibidem 1.

[53] Ibidem 3.

[54] Vlado Azinović, Kurt Bassuener, and Bodo Weber, ‘Assessing the potential for renewed ethnic violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A security risk analysis’, Atlantic Initiative and Democratization Policy Council, October 2011, 65.

[55] Schindler, Unholy Terror, 237-271.

[56] Azinović, ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Nexus with Islamist Extremism’, 13. See also Bećirević, Halilović, and Azinović ‘Literature Review: Radicalization and Violent Extremism in the Western Balkans’, 18. ‘In the region [Western Balkans], the two most concentrated locations are in BiH, in Gornja Maoča and Ošve. In these places, Salafists are unfriendly to outsiders, live in isolation, and have repeatedly challenged the rule of law and the authority of the state with attempts to influence education curricula. These villages are also known for providing foreign fighters to Syria and Iraq.’

[57] Azinović, Bassuener, and Weber, ‘Assessing the potential for renewed ethnic violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A security risk analysis’, 65.

[58] Author interview with a knowledgeable source.

[59] E-mail to the author on November 15, 2020 from an international practitioner with years of experience in Bosnia in the intelligence reform process.

[60] Nedim Jahić, ‘The Evolution of the SDA: Ideology Fading Away in the Battle of Interests’, Balkan Insight, May 27, 2015. See: https://balkanist.net/the-evolution-of-the-sda-ideology-fading-away-in-the-battle-of-interests/.

[61] E-mail to the author on November 15, 2020 from an international practitioner with years of experience in Bosnia in the intelligence reform process.

[62] Azinović, ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Nexus with Islamist Extremism’, 12.

[63] Radovan Karadžić retained his command of the RS parallel power structure even after indictment for war crimes by ICTY and subsequent removal from his formal position as President in 1996.

[64] ‘Bosnia’s Stalled Police Reform: No Progress, No EU’, International Crisis Group report #164, September 6, 2005, i, 2.

[65] UN Office on Drugs and Crimes, ‘Crime and its Impact on the Balkans and affected Countries’, 53.

[66] ‘Bosnia’s Stalled Police Reform’, 3.

[67] Griffiths, ‘Investigation: Will Europe Take on Bosnia’s Mafia?’.

[68] Group of States against Corruption, ‘First Evaluation Round – Evaluation Report on Bosnia and Herzegovina’, Strasbourg, July 11, 2003, 91.

[69] Milkica Milojevic, ‘Republika Srpska: Corruption in the Media, AIM Banja Luka’, 3. See: http://www.aimpress.ch/dyn/dos/archive/data/2001/11029-dose-01-08.htm.

[70] Milojevic, ‘Republika Srpska: Corruption in the Media’.

[71] Reuf Bajrović, Richard Kraemer, and Emir Suljagić, ‘Bosnia on the Chopping Block: The Potential for Violence and Steps to Prevent it’, Foreign Policy Research Institute, March 2018, 8.

[72] Roger D. Petersen, Western Intervention in the Balkans: The Strategic Use of Emotion in Conflict (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 2011), 305.

[73] ‘Milorad Dodik Wants to Carve Up Bosnia. Peacefully, if Possible’, The New York Times, February 16, 2018; Florian Bieber, ‘Patterns of competitive authoritarianism in the Western Balkans’, in: East European Politics 34 (2018) (3) 337–54. See: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21599165.2018.1490272.

[74] Aida Cerkez, ‘AP Exclusive: Bosnian Serbs given ultimatum’, Associated Press, May 5, 2011. See: https://web.archive.org/web/20110513043752/http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20110505/ap_on_re_eu/eu_bosnia_ultimatum.

[75] Cerkez, ‘AP Exclusive: Bosnian Serbs given ultimatum’.

[76] Drazen Remikovic, ‘BiH divided over abolishing armed forces’, Southeast European Times, October 20, 2012. See: https://web.archive.org/web/20121021031100/http://setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2012/10/20/feature-01.

[77] The international judges and prosecutors on BiH’s Organized Crime and Corruption Chamber were discontinued in 2010.

[78] ‘Dodik’s repeated calls for Republika Srpska secession raise alarm’, Al Jazeera, February 18, 2020. See: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/2/18/dodiks-repeated-calls-for-republika-srpska-secession-raise-alarm.

[79] Kurt Bassuener, ‘The Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Unfulfilled Promise’, Democratization Policy Council, October 2015, 1, 35.

[80] Bassuener, ‘The Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina’.

[81] Bajrović, Kraemer, and Suljagić, ‘Bosnia on the Chopping Block’, 6.

[82] Kurt W. Bassuener, ‘Written Statement for the Congressional Record’, House Foreign Affairs Committee Hearing, ‘The Dayton Legacy and the Future of Bosnia and the Western Balkans’, April 18, 2018, 2. See: https://foreignaffairs.house.gov/2018/4/dayton-legacy-and-future-bosnia-and-western-balkans.

[83] In addition to Karadžić and Mladić, the most prominent were Biljana Plavšić and Momčilo Krajišnik. See: The International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia, ‘About the ICTY: The Cases’, Updated January 22, 2009. See: https://web.archive.org/web/20090126094544/http://www.icty.org/sections/TheCases/KeyFigures.

[84] Department of Treasury, ‘Treasury Sanctions Republika Srpska Official for Actively Obstructing The Dayton Accords’, January 17, 2017. See: https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0708.aspx.

[85] See Nedim Dervisbegovic, ‘For Bosnia’s Dodik, Referendum Law Means It’s Make-Or-Break Time’, Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty, February 11, 2010, 1. When the RS parliament passed a law in 2010 allowing for referendums, “The U.S. Embassy in Sarajevo…warned that it would interpret as ‘provocative’ any referendum that ‘threatens the stability, sovereignty, or territorial integrity’ of the Balkan country.”

[86] Bassuener, ‘Written Statement for the Congressional Record’, Foreign Affairs Committee Hearing, April 18, 2018, 2.

[87] Mladen Dragojlovic, ‘BiH has failed to implement the recommendations of GRECO’, Independent Balkan News Agency, October 23, 2019.

[88] See Valery Perry, ‘Frozen, stalled, stuck, or just muddling through: The post-Dayton frozen conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, Asia Europe Journal, August 23, 2018, 1, 16. See: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-018-0525-6. Perry ‘argues that BiH can be categorized as a frozen conflict, as the core issues at the heart of the violent conflict of the 1990s have not been resolved’. One of the contributing factors identified by Perry is ‘Privatization to date in Bosnia and Herzegovina has been largely used for the formation of economic “elites” within the three dominant ethnic groups…The World Bank further describes the resulting dynamic on patron-client networks in BiH’.

[89] Daniel Hamilton in Fixing Dayton proposes the most coherent path to breaking the gridlock that parallel power structures have produced: constitutional reform incentivized by the international community that is in turn led by Bosnian civil society. Many complicated pieces would need to be put in place, however, for this to materialize, including effective collaboration between the US, EU, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund, reinvigoration of the Bonn Powers, a clear signal by the EU that it is willing to admit Bosnia if it were to meet their criteria for membership, and a restoration of the European Force and NATO deterrent capability. While this posits the most reasonable strategy for resolving Bosnia’s impasse, it remains unclear if the many daunting obstacles can be overcome.

[90] NATO Stability Police Center of Excellence, ‘Assessment of Spoiler Threats-A Shared Requirement’, May 27, 2020. See: https://www.nspcoe.org/events-news/news/2020/05/27/assessment-of-spoiler-threats-a-shared-requirement.

[91] Dziedzic, et al, ‘SFOR Lessons Learned in Creating a Secure Environment for the Rule of Law’, 10.

[92] Dziedzic, ‘NATO Should Promptly Implement Stability Policing. Why and How’, 56-71.