In 1873 the colonial government of the Dutch East Indies launched a military expedition against the Sultanate of Aceh. The expedition failed and a second expedition would soon follow. Sixty-nine bloody years later the conflict ended with the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies. The Aceh War turned out to be the longest and bloodiest colonial war the Kingdom of the Netherlands ever fought. This article purports to provide in-depth knowledge on the justification of the first Dutch military expedition against Aceh. An analytical framework, based on ‘securitisation’ and complemented with speech act theory, framing theory, and rhetoric, is used to analyse the correspondence between Dutch government officials and the Sultan of Aceh. This article proposes that the Acehnese ‘threat’ was securitised by the Governor General in the Dutch East Indies among the political elite in the Netherlands in order to circumvent standard political procedures in favour of colonial expansion in Northern Sumatra.

Major S. de Winter MA*

On March 26, 1873 the colonial government of the Dutch East Indies presented the Sultan of Aceh with a declaration of war.[1] The ensuing war resulted in the subjugation of the Sultan in 1903, the conquest of Aceh in 1913, and an armed insurgency that was to linger on until the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies in 1942.[2] According to the Dutch the initial military expedition was launched in response to the Sultan’s animosity towards the Dutch colonial government, the instability of the Acehnese Sultanate, and the subsequent threat to the stability of Northern Sumatra. In short, considerations of sovereignty and self-defence drove the Dutch to war. But was this really the case? Did the Sultan of Aceh pose a real threat to the security of the Dutch colony in Northern Sumatra? It is more likely the Dutch colonial government dramatised the threat of the Acehnese Sultanate to justify a war of colonial expansion. To support this theory in-depth knowledge on the justification of the Dutch military expedition against Aceh in 1873 will be provided.

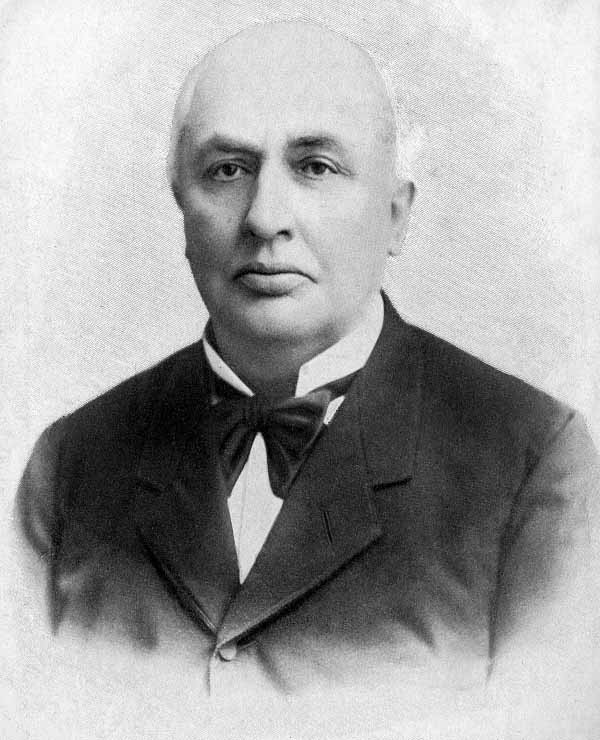

Heavy fighting between Dutch colonial troops and Acehnese warriors at the Mesigit during the first Dutch military expedition in Aceh. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

In order to understand the justification of the war against Aceh I will first focus on the historical context, the prelude to war. The next section clarifies the employed method of research followed by a section in which the scope of this research is defined. The main part of this article contains three sections analysing the justification of the Aceh War through three different lenses of the research framework. A summary of the results that serves to defend the aforementioned theory concludes this article.

Historical context

As early as 1599 the first Dutch merchants came in contact with the Sultanate of Aceh in the northern part of the island of Sumatra. A few years after the small merchant fleet of the De Houtman brothers had visited Aceh, the Dutch established trade with the Sultanate’s landlords.[3] But the Dutch were not alone. The early merchants and their successors of the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) had to compete with predominantly English traders from the British East India Company. To define their respective spheres of influence the British and Dutch signed several treaties regulating free trade and shipping. The first Treaty of London, signed in 1814, merely restored Dutch rule over its former colonies in the East Indies after the British had seized them during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1824 both countries signed a second treaty in London, the Sumatra Tractate, in which Great Britain agreed to abandon its claim on territories in Sumatra. In exchange the Dutch were to safeguard Aceh’s independence and had to guarantee free commerce and shipping along the coast of Sumatra.[4] Subsequently, in 1857 Dutch and Acehnese representatives signed a bilateral treaty on ‘Commerce, Peace, and Friendship’ that settled their relations and addressed issues regarding Dutch colonial expansion on Sumatra and Acehnese piracy along the coast.[5] Nevertheless, piracy remained a threat to commerce in the coastal waters of Northern Sumatra.[6] According to the Sumatra Tractate the Dutch colonial government had to act firmly against this threat coming from Aceh.

Despite the 1824 Anglo-Dutch treaty the Sultan tried to re-establish relations with an old ally, the Ottoman Empire, in 1868 by sending his most prominent adviser to Constantinople.[7] The goal was to have the Ottoman Sultan declare Aceh a protectorate of the Ottoman Empire to rule out Dutch or British dominance. The diplomatic mission failed. With the Suez Canal completed in 1869 the most important shipping route to the Indies ran along the coast of Northern Sumatra. Thus control over the coast of Aceh became ever more important to the Dutch and British.[8] In 1871 the Netherlands and Great Britain signed a third treaty. In the Second Sumatra Tractate both countries agreed that the Dutch could advance their sovereign claims over Aceh in exchange for free shipping and commerce for British traders on the island of Sumatra. [9] Thus, according to the Dutch and British Aceh was finally brought under Dutch sovereign rule.

A 19th-century Dutch map of Aceh: after the conquest of the region in 1913 an armed insurgency lingered on until the Japanese invasion in 1942. Source: Winkler Prins/NIMH

The direct cause for the first military expedition against Aceh lies in an attempt by the Acehnese Sultan, Aladdin Mahmoud Shah, to establish political relations with other foreign powers. The political move by the Acehnese was understandable considering increasing Dutch attempts to bring the Sultanate under its control. This time Acehnese envoys approached the Italian and American consulates in Singapore. The Dutch Consul General W.H. Read in Singapore made the ‘act of treason’ public on February 20, 1873 in a letter to the General Secretary of the Dutch East Indies.[10] Under the influence of the Minister of Colonies I.D. Fransen van de Putte the Vice President of the Council of the East Indies, F.N. Nieuwenhuijzen, was appointed as Commissary for Aceh by Governor General J. Loudon.[11] Whereas the latter reported to Minister Fransen van de Putte, the new Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen was accountable to Governor General Loudon. As Minister of Colonies in 1861, Loudon was strongly opposed to further expand the Dutch colony in the East Indies.[12] Nevertheless, it was he as Governor General who stressed the urgency for a strong ultimatum to Aceh among the political elite in the Netherlands twelve years later. Fransen van de Putte, in his second tour as Minister of Colonies, was not fully convinced of the sensibility of Loudon’s proposed course of action.[13] Nonetheless, on March 22, 1873 Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen wrote a letter to the Sultan asking him to clarify his actions. The Sultan’s indistinct reply to this letter, as well as to a second letter dated March 24, prevented further disagreement between Loudon and Fransen van de Putte.[14] The following day, March 26, 1873, on board his majesty’s steamer Citadel van Antwerpen off the coast of Aceh, Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen wrote a manifesto of war (Oorlogsmanifest) to the Sultan. In this document the government of the Dutch East Indies stated it would resort to ‘forceful means to safeguard the state of affairs in both its general commercial interest as well as the demands of her own security in Northern Sumatra’.[15] The result of Nieuwenhuijzen’s Oorlogsmanifest was a protracted conflict that was to last for almost seventy years and allegedly took the lives of a 100,000 Acehnese and Dutch.[16]

Research scope

The Oorlogsmanifest is part of a carefully selected set of seventeen letters regarding the Dutch declaration of war.[17] The letters were written between the Minister of Colonies and the Governor General of the Dutch East Indies on the one hand and between the Sultan of Aceh and the Commissary for Aceh on the other. They are divided into two corresponding categories. The first category comprises three letters with eight appendices from Governor General James Loudon in Batavia to the Minister of Colonies Isaäc Dignus Fransen van de Putte in The Hague.[18] Loudon’s letters, classified as secret cabinet documents, reveal an enormous amount of information on the cause of the war, the underlying motives, and the Dutch attitude towards the Acehnese leadership.[19] More importantly, these letters are to be seen as the internal speech act aimed at the political elite in The Hague. The second category of texts is defined as the external part of the speech act and is presented in the form of diplomatic correspondence between Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen and the Sultan of Aceh. Their correspondence is reproduced in a letter from the former to Governor General Loudon dated March 26.[20] The appendices to this letter are two letters from the Commissary to the Sultan in which he asks for full compliance with the Dutch demands,[21] two replies from the Sultan,[22] and the actual manifesto of war.

Minister of Colonies Isaäc Dignus Fransen van de Putte. Photo Spaarnestad/Collectie Nationaal Archief

Methodology

A literature study provided a research framework based on securitisation theory and aided by speech act theory, framing theory, and classical rhetoric.[23] Within this framework the concept of securitisation is employed as a starting point, while speech act theory, framing theory, and rhetoric are employed as instruments to demonstrate securitisation. Balzacq defines securitisation as ‘a set of interrelated practices, and the processes of their production, diffusion, and reception/translation that brings threats into being.’[24] Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde argue that ‘the invocation of security has been the key to legitimising the use of force.’[25] According to them securitisation is the process in which an issue of public debate is escalated beyond conventional political rules by presenting it ‘…as an existential threat, requiring emergency measures….’[26] The essential element of ‘existential threat’ in their definition should be noticed as well as the requirement that the audience accepts the existential nature of the threat.[27] If a security issue is presented as existentially threatening without the audience accepting it as such they call this a ‘securitising move’.[28] In this article I follow Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde’s definition of securitisation.

Securitisation works through the use of speech acts,[29] frames and narratives, and rhetoric.[30] According to Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde speech act theory is the primary vehicle through which the concept of securitisation takes place. Framing theory is employed as a second instrument to explain how frames and narratives position speech acts. Rhetoric is the final instrument through which the notion of an existential threat is conveyed on an audience. If we are to prove that the Acehnese threat was securitised we need to confirm the use of speech acts, frames and narratives, and rhetoric by the Dutch colonial government. Studying the written correspondence between the four key players by way of the research framework will reveal the techniques employed by the Dutch colonial government to justify its military expedition against Aceh. Thus, speech act theory, framing theory, and rhetoric provide the necessary instruments to determine whether the Acehnese threat was actually securitised. For each instrumental theory separate research criteria are defined in the first paragraphs of the following three sections.

Speech Acts

The student of speech act theory is aware of the power of discourse in creating reality and moulding truth with words. Speech acts are ‘forms of representation that do not simply depict a preference or view of an external reality but also have a performative effect.[31] A speech act invokes a truth by uttering what J.L. Austin calls ‘performative sentence[s]’.[32] Performatives, like ‘I declare war’, do not describe a phenomenon or state a fact, they perform an act. Such ‘acts’ in a speech act suggest the ability of language not only to reflect on the world but also to engage in its construction.[33] Whether a security issue is actually constructed can be determined by the textual analysis of a speech act.[34] What we are looking for in a speech act are three types of ‘units of security analysis’ and three ‘facilitating conditions’ in order to confirm whether an issue is securitised or not.[35]

The authors of the Copenhagen School advance the term ‘facilitating conditions’ to explain how securitisation takes place through a speech act. First and foremost, a speech act is conveyed through the use of ‘accepted conventional procedures’ pertaining to the language and grammar of security.[36] Secondly, a successful speech act must be performed by ‘an actor with authority’ in a security matter. And thirdly, the actor must refer to ‘specific features of a security issue’ for it to be accepted by an audience as existentially threatening.[37] In addition to the three facilitating conditions each speech act involves three types of units: a securitising actor, a functional actor, and a referent object. Only when a securitising actor succeeds in convincing a functional actor (an audience or third party with significant influence in the security issue) of an existential threat to a referent object will securitisation be successful.[38] The three required units of security analysis together with the three facilitating conditions that shape an existential threat form our research criteria to examine securitisation of the Aceh case.[39]

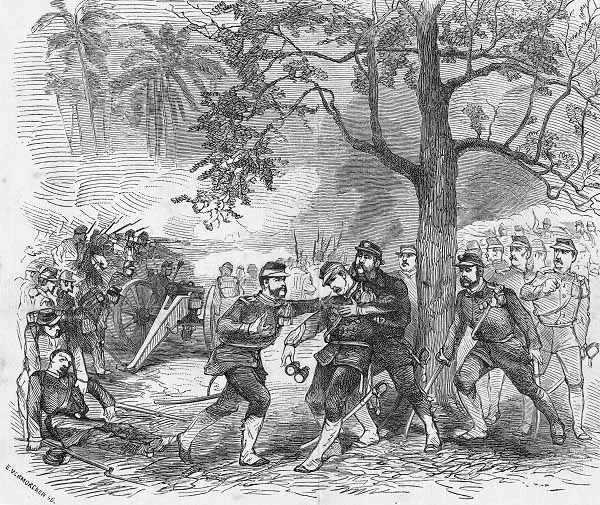

Major General Köhler, the commander of the first Aceh expedition, was killed during the fighting. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen’s manifesto of war and accompanying letters to the Sultan are to be regarded as a securitising move rather than a securitising speech act. First, the textual analysis of the Oorlogsmanifest produces ambiguous results with regard to the functional actors. Being the author of the Oorlogsmanifest Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen is the logical securitising actor. As such, he designates British and Dutch merchants and the Dutch colonial government as referent objects that are threatened by the Acehnese.[40] According to Nieuwenhuijzen general interests of commerce and shipment are threatened in the economic sector by mutual disputes and hostilities between subordinate states of the Acehnese Sultanate. With regard to the political sector he states that it has become impossible for the Dutch colonial government to guarantee security for Northern Sumatra without resorting to forceful measures against Aceh. In the Oorlogsmanifest Nieuwenhuijzen addresses primarily the Sultan and secondary the Western consuls in Singapore as functional actors.[41] Nevertheless, the Sultan is an odd functional actor since he himself is perceived to be the cause of the security issue at hand. In addition, the Western consuls in Singapore were in no position to influence political decision-making by the Dutch colonial government since the latter already decided to commence hostilities. Therefore, the Oorlogsmanifest is ambiguous with regard to the units of security analysis and specifically considering its functional actor or audience.

Second, the Oorlogsmanifest fails to meet the three facilitating conditions since Nieuwenhuijzen is unable to persuade his audience of the existential nature of the threat. Although Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen had been given the authority to declare war on Aceh,[42] and despite his use of conventional security grammar,[43] the threat of the Acehnese instability is not directly aimed at the Dutch colonial government. To construct an existential threat Nieuwenhuijzen would have had to advance foreign threats to the Dutch sovereign claim on Sumatra. However, Loudon explicitly forbade him to do so.[44] Since the Oorlogsmanifest remains ambiguous on the functional actors and fails to construct an existential threat it has to be regarded as a securitising move instead of securitisation.

A textual analysis of Governor General Loudon’s letters to the Minister of Colonies Fransen van de Putte produces different results. As Governor General Loudon certainly would have acted as the appropriate securitising actor with the right amount of authority to decide on matters of state. In fact, it is Governor Loudon who instructs Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen how to correspond with the Sultan of Aceh.[45] In contrast to the Oorlogsmanifest, Loudon’s letters produce an unambiguous functional actor: the Dutch Cabinet. The political elite in The Hague certainly would have been able to ‘significantly influence decisions in the field of security’ with regard to the Acehnese question.[46] In case of Loudon’s letters the referent object is the Dutch colony in the East Indies since he tries to persuade Minister Fransen van de Putte of the ‘urgent’ necessity to act ‘forcefully’ to the threat of ‘foreign influences and elements’ against Dutch sovereign claims on Sumatra. We can conclude that Loudon’s letters are unambiguous with regard to the units of security analysis.

Loudon’s internal speech act also meets the three facilitating conditions of securitisation. First, we have already shown that Loudon was perceived to speak with authority on the security issue concerning Aceh by his audience. Secondly, he uses utterances belonging to the accepted security grammar by advancing that the existence of the Dutch colonies is threatened. Moreover, Loudon explains his decision to convene an ‘extraordinary meeting’ of the colonial government.[47] He reasons that there is an ‘advanced urgency’ to act timely, and that there is no time to wait for ‘mathematical certainty’.[48] Furthermore, Loudon depicts the threat of foreign intervention in Aceh as the sword of Damocles hanging over the head of the colonial elite in the coming years if it is not confronted timely by a ‘military show of force’.[49] Thirdly, Loudon constructs the Acehnese threat through the use of specific threatening features such as the treacherous nature of the Acehnese leaders and their ‘ambiguous politics’.[50] If the Cabinet fails to grasp that a point of no return has been reached, and refrains from a timely response in the way that Loudon proposes, it will lead to ‘all sorts of great difficulties and eventually the loss of Sumatra’.[51] Moreover, Loudon considers the financial expenses of the proposed military expedition justified by the premise that delaying military action would only result in more expenses and a larger loss of lives in later expeditions.[52] Thus, Governor General Loudon succeeds in constructing an existential threat whilst proposing war as the only viable option left to the Dutch Cabinet.

The textual analysis therefore discloses that Loudon’s intentions can be considered as a securitisation of the Acehnese question among the Dutch political elite. On the other hand, Nieuwenhuijzen’s Oorlogsmanifest fails to communicate an existential threat to the appropriate functional actors. Therefore, I regard Loudon’s letters as the securitising speech act while Nieuwenhuijzen’s correspondence is to be considered as the justifying speech act.

Frames and narratives

For a speech act to be convincing it is important to position it within a common framework of reference. Frames limit the public debate by establishing ‘the sensuous parameters of reality itself’.[53] By emphasising certain aspects of a security issue, other points of view on the matter are intentionally omitted. Therefore, framing is used as a technique to manipulate the public discourse on an event ‘in which certain aspects of reality are promoted over alternatives’.[54] The frames used by Loudon and Nieuwenhuijzen are embedded in a broader political context, or narrative.[55] In the second half of the 19th century the political context in the Netherlands was characterised, among others, by a legalistic and moralistic approach to international relations in general and the rise of modern imperialism regarding its colony in the East Indies.[56] Therefore, we assume that the speech acts by Loudon and Nieuwenhuijzen are presented along the narratives of the just war tradition and imperialism.

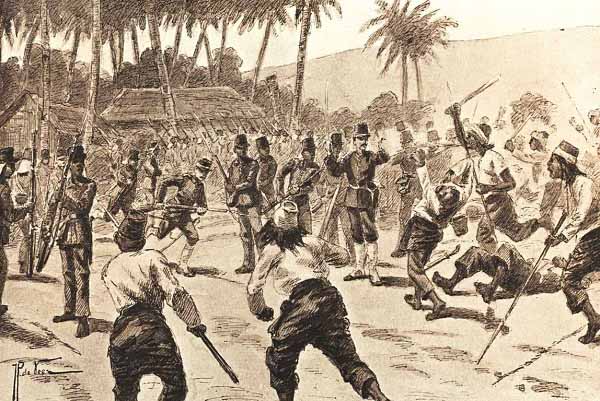

Fighting during the first military expedition to Aceh. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Just war doctrine explains when war is criminal and when it is lawful.[57] In his book Just and Unjust Wars Michael Walzer explains how the moral judgment of war evolved over time into an international legal framework that informs people about the legality of war.[58] The ‘legalist paradigm’ stresses the necessity to resist and punish the violation of territorial integrity and political sovereignty as the basic rights for states.[59] In short, just war theory regards war only permissible in self-defence. The concept of imperialism is at odds with just war theory. By examining imperialism as a narrative to frame the war against Aceh, this article turns to the work of Elsbeth Locher-Scholten on colonial expansion in the East Indies.[60] She argues that early theories of imperialism regard economic incentives and interests of capitalists as the primordial motives for imperialistic expansion. Dutch imperialism in the 1870s can best be seen as a reaction to both ‘the development of the world market’ and the desire of other Western powers to expand their colonial possessions.[61] In short, imperialism was driven by economic incentives and the inclination to compete with other (colonial) empires over unconquered territory.

The textual analysis shows that Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen was keen to stress the hostile attitude of the Sultan and the instability of the Sultanate as a threat to Dutch security in Northern Sumatra. The Oorlogsmanifest implies that without forceful means the Dutch colonial government would no longer be able to safeguard its own security in Northern Sumatra. In other words, the military expedition is just because it is launched in self-defence. According to Nieuwenhuijzen, it is the unwillingness and inability of the Acehnese Sultan to restore peace and order in his realm and his apparent preparations for war that provided the colonial government with a legitimate reason to use force. Moreover, Nieuwenhuijzen emphasises the righteousness of the war by stating that several Acehnese subordinate states requested protection by the Dutch colonial government from the Sultan. A close inspection of Loudon’s letters to the Minister of Colonies results in a slightly different and more aggressive rationale for war. Although Loudon also strengthens his plea with an appeal to self-preservation he reasons that a declaration of war would legally prevent an American intervention in Aceh and would safeguard the Dutch sovereign right to control Aceh.[62] He argues that if Aceh was to refuse Dutch demands, the Dutch could resort to stronger demands ‘once the weapons have been revealed’.[63] While Loudon underlines the threat of foreign intervention to Dutch political sovereignty, Nieuwenhuijzen emphasises the threat posed by the Sultanate to the security of the Dutch colony itself. Since Loudon specifically appeals to the violation of political sovereignty and Nieuwenhuijzen strongly advances the necessity to react in self-defence we can establish that both tried to frame the military expedition as a just war.

The textual analysis of Nieuwenhuijzen’s letters to the Sultan shows no sign of reference to an imperialistic narrative. Although he does mention the Dutch commerce and shipment interests and vaguely speaks of the attempts to establish ‘amicable relations’ with Aceh, the Oorlogsmanifest does not frame the war as a matter of imperialism.[64] Loudon’s underlying correspondence with the Minister of Colonies in turn is full of imperialistic speech. Throughout his letters he continuously refers to the Dutch sovereign claim on Sumatra and the Sultan’s refusal to accept Dutch authority. Furthermore, by using phrases such as ‘Dutch existence on - and possession of Sumatra’ and advancing arguments for a forceful response to Italian and American attempts to establish relations with the Sultan, Loudon displays an imperialistic view on the Acehnese question.[65]

In sum, both Nieuwenhuijzen and Loudon try to frame the war according to the just war doctrine. Yet only Loudon employs the imperialistic narrative to justify the war in his correspondence with the Dutch government in The Hague. Whereas the military expedition is publicly framed as a war in defence of the Dutch colony on Sumatra, it is framed among elite political circles as a natural imperialistic reaction to growing commercial interests and foreign tendencies to colonial expansion.

Governor General James Loudon. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Rhetoric

As the unsurpassed instrument to influence an audience, rhetoric comprises the third and final analytical element of the textual analysis. Rhetoric, according to Sam Leith is ‘the art of persuasion.’[66] Before we can analyse what gave the words of Nieuwenhuijzen and Loudon their persuasive appeal, we must first understand how rhetoric works. Rhetoric, Leith says, ‘consists of five parts: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery.’[67] We cannot examine the last two parts by means of a textual analysis. In addition, we presume the general style of the texts to be identical even if their purposes differ.[68] Therefore, the criteria for analysis are drawn from ‘invention’ and ‘arrangement’. The next paragraph subdivides ‘invention’ into three subsequent criteria for analysing rhetoric and explains how a speech act is ‘arranged’ according to classical rhetoric.

Aristotle divided the process of invention into ‘three different lines of argument, or persuasive appeal’: ethos, logos, and pathos.[69] Ethos pertains to the appeal to authority by the speaker and the way he seeks to connect with his audience.[70] Logos is the appeal to reason by sounding logical through the use of premises, commonplaces, analogies, and generalisation.[71] Pathos is the appeal to emotion.[72] In order to be able to find authority, reason, and emotion in a speech act we must first know where to find them. Leith argues that a speech act is arranged according to six consecutive components: exordium, narration, division, proof, refutation, and peroration.[73] The strongest appeal to authority is to be found in the exordium or introduction.[74] The appeal to reason is primarily found in the proof and refutation, while emotion is predominantly found in the peroration or conclusion. For the sake of conciseness I will not elaborate further on the six arrangements of a speech act, since we now know to look for authority, reason, and emotion in the introduction, proof, refutation, and conclusion of a speech act. With this knowledge I will first examine Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen’s letters before studying Governor-General Loudon’s correspondence.

Nieuwenhuijzen appeals to his audience by stating his authority as the Commissary for Aceh. In fact, in his first letter to the Sultan he explains that he has been delegated on behalf of the colonial government to negotiate with the Sultan.[75] Nieuwenhuijzen appeals to reason by advancing in his manifesto two arguments in support of the justification of war. First, he argues that the repeated attempts of the colonial government to establish amicable relations with the Acehnese leadership in order to maintain peace and stability in the archipelago have been met with reluctance and indifference and an inability of the Acehnese rulers to change their course. Second, the Dutch sympathetic advances are met with ‘far-reaching disloyalty’.[76] The appeal to reason is supported by a refutation based on the premise that the Sultan ‘wilfully mocks’ the colonial government and wishes to continue his bellicose point of view because he repeatedly fails to refute the grievances against him and publicly prepares for battle.[77] Furthermore, the premise that the rulers of Aceh lack good faith and are not to be trusted is based on the perceived violation of the 1857 treaty of ‘Commerce, Peace, and Friendship’, proving their disloyalty.[78] In his conclusion, Nieuwenhuijzen shapes the perception of his audience, without a strong appeal to emotion, by repeating that the Dutch can no longer refrain from forceful measures in order to safeguard ‘the general interests of commerce and the demands of their own security in Northern Sumatra’.[79]

Unlike Nieuwenhuijzen, in his letters to the Cabinet, Loudon does not invoke his authority.[80] His appeal to reason also differs from Nieuwenhuijzen. According to Loudon, the true argument for military intervention in the Sultanate of Aceh is to exclude ‘foreign influences and elements from Northern-Sumatra.’[81] In his February 25 letter Loudon justifies his decision to force war upon Aceh on the premises that a strong military display of power will persuade the Acehnese to revert to peaceful solutions and that without such forceful measures the threat of foreign intervention will remain a challenge to Dutch sovereignty and dignity.[82] Loudon also uses the analogy of the French-German war of 1870 to persuade Minister Fransen van de Putte that the declaration of war does not necessarily have to be followed by a direct opening of hostilities.[83] With respect to the appeal to emotion Loudon, in contrast to Nieuwenhuijzen, makes an extraordinary moving plea to justify the course of action taken by the colonial government against Aceh. He accuses the Acehnese of ambiguous politics towards the colonial government and argues that Aceh will remain a weak spot to the Dutch as long as its leaders do not recognise Dutch sovereignty. Therefore, he insists on a military solution to present possible foreign interveners with a fait accompli. Only a rapid military action offers a chance on keeping Sumatra pacified without having to send an even larger force in the future. After all ‘Aceh has cast the die’ and it is now up to the Dutch to defend their dignity with force.[84]

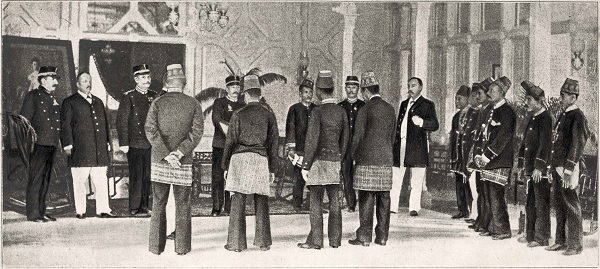

Subjugation of the Acehnese Sultan to General J.B. van Heutsz. Photo Spaarnestad/Collectie Nationaal Archief

The textual analysis shows that both Nieuwenhuijzen and Loudon employ specific rhetorical techniques to persuade their audiences of the necessity of war. However, differences in the use of rhetoric were found. Whereas Nieuwenhuijzen had to make a strong appeal to character, Loudon obviously did not. Second, while Loudon could appeal to reason in securitising Dutch sovereignty in Sumatra, Nieuwenhuijzen could not out of political considerations. And third, whilst Loudon sought to move his audience by emotion Nieuwenhuijzen rather based his argumentation on reason.

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated that the Dutch colonial government securitised the threat of the Acehnese Sultanate to justify a war of colonial expansion. Whereas the first military expedition was publicly justified as a war of self-defence by the colonial government, imperialistic motives prevailed. The speech act analysis reveals that Governor General Loudon was successful in securitising the Acehnese question among the political elite in the Netherlands. Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen’s public declaration of war on the other hand failed to pass the securitisation test and is to be regarded merely as a securitising move. The framing analysis discloses that the first military expedition was publicly framed as a just war in defence of the Dutch colony on Sumatra. However, internally the expedition was framed as an imperialistic reaction to growing commercial interests and foreign desires for colonial expansion in Aceh.

The rhetorical analysis discloses strong differences in the appeal to character, reason, and emotion. Those differences are most noticeable in the latter. Loudon sought to persuade his audience, the political elite in the Netherlands, with a strong emotional plea for a rapid reaction to prevent foreign intervention in Aceh and to safeguard commercial interests along its coast. The results show us that Governor General Loudon was able to construct an existential threat to the Dutch colony in Northern Sumatra. By securitising the threat of the Acehnese Sultanate, the colonial government was able to circumvent normal political procedures in favour of a swift military expedition to expand its colony on Sumatra.

* Sjoerd de Winter is a staff officer for safeguarding processes at the Integration Department of the Dutch Army. Before that he worked at 11 Infantry Battalion ‘Garde Grenadiers & Jagers’ and at 12 Infantry Battalion ‘Regiment Van Heutsz’.

[1] The original text of the Oorlogsmanifest, is available on the internet as part of the booklet Officieele Bescheiden betreffende het ontstaan van den Oorlog tegen Atjeh in 1873:

https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/129726?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=75d1bfa30862b7287b74&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=24&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=17.

[2] The opinions on the duration of the war differ. Some authors argue that the war ended in 1903, while others argue that Aceh was conquered by 1913. However, most authors agree that the insurgency was never completely defeated until the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies in 1942. I consider the Aceh War to be a protracted conflict that raged in various manifestations between 1873 and 1942.

[3] A. Stolwijk, Atjeh: het verhaal van de bloedigste strijd uit de Nederlandse koloniale geschiedenis (Amsterdam, Prometheus, 2016).

[4] P. van ’t Veer, De Atjeh-oorlog, (Amsterdam, De Arbeiderspers, 1969).

[5] Van ’t Veer, De Atjeh-oorlog.

[6] Van ’t Veer, De Atjeh-oorlog; Stolwijk, Atjeh: het verhaal van de bloedigste strijd.

[7] Stolwijk, Atjeh: het verhaal van de bloedigste strijd.

[8] H.W. Van den Doel, Het Rijk van Insulinde (Amsterdam, Prometheus, 1996).

[9] P. van ’t Veer, ‘Atjeh 1873: een oorlog op papier’, in: De Gids 130 (1967) (3) 166.

[10] W.H. Read was from Scottish descent.

[11] Van ’t Veer, De Atjeh-oorlog.

[12] Van ’ t Veer, De Atjeh-oorlog, 15.

[13] Van ’t Veer, De Atjeh-oorlog.

[14] Van ’t Veer, ‘Atjeh 1873’.

[15] F.N. Nieuwenhuijzen, Oorlogsmanifest, dd. 26 maart 1873.

[16] A.J.S. Reid, The Blood of the People. Revolution and the End of Traditional Rule in Northern Sumatra (Singapore, NUS Press, 2014); Van ’t Veer, De Atjeh-oorlog.

[17] The letters, among other official documents, were published by the Dutch government in 1881 as part of the aforementioned booklet Officieele Bescheiden betreffende het ontstaan van den Oorlog tegen Atjeh in 1873. https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/129726?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=75d1bfa30862b7287b74&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=24&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=17.

[18] The first letter dates from February 25: Loudon, Brief van 25 Februarij 1873, la. P, no. 13, Kabinet-geheim. The appendix contains further evidence for the perceived treacherous act of the Acehnese envoys in Singapore. Read, Brief van den Consul-Generaal te Singapore aan den Algemeenen Secretaris van het Nederlandsch-Indisch Gouvernement, dd. 20 Februarij 1873, no. 25. The second letter dates March 4 1873: Loudon, Brief van 4 Maart 1873, 1a. R. no. 14, geheim. This letter is accompanied by two appendices containing instructions for the diplomatic mission of Commissary Nieuwenhuijzen by Council of the Dutch East Indies and an extract from a letter of the Ruler of Riouw D.W. Schiff who confirms the Acehnese treason in Singapore. The third and final letter from Loudon to Fransen van de Putte before the opening of hostilities was send on March 14: Loudon, Brief van 14 Maart 1873, la. W. no. 1V, Kab. Geheim. This letter contained five appendices, including two additional letters from Consul General Read: Read, Extract uit een brief van den Consul-Generaal Read aan den Gouverneur-Generaal Loudon, dd. 3 Maart 1873; Read, Extract uit een brief van den Consul-Generaal READ aan den Gouverneur-Generaal Loudon, dd. 6 Maart 1873, two letters from the American consul in Singapore: Studer, Brief van den Amerikaanschen Consul te Singapore voor den sjabandar van Atjeh; Studer, Instructie te Singapore voor Tongkoe Mohamad Ariffin opgesteld, and a letter from Tonkoe Mohamad Ariffin one of the Acehnese envoys visiting Singapore who unmasked the ‘treacherous’ Sultan to the Dutch: Brief van Tongkoe Mohamad Ariffin aan den resident van Riouw, dd. 3 Maart 1873.

[19] According to the March 14 letter to Minister Fransen van de Putte, Nieuwenhuijzen was instructed by Loudon, at the request of the Minister, not to use the defence of Dutch sovereignty in Sumatra publicly as an argument for war: ‘Souvereiniteit moet uitvloeisel zijn van onderhandelingen of van oorlog, maar kan wegens indruk naar buiten niet als eerste eisch ruw weg (sic) op den voorgrond worden gesteld.’ Loudon, Brief van 14 Maart 1873, la. W. no. 1V, Kab. Geheim.

[20] F.N. Nieuwenhuijzen, Brief van den Gouvernements-Commissaris voor Atjeh aan den Gouverneur-Generaal, 26 Maart 1873.

[21] F.N. Nieuwenhuijzen, Brief van den Gouvernements-Commissaris aan den Sultan van Atjeh, dd. 22 Maart 1873; F.N. Nieuwenhuijzen, Brief van den Gouvernements-Commissaris aan den Sultan van Atjeh, dd. 24 Maart 1873.

[22] Syah, Brief van den Sultan aan den Gouvernements-Commissaris, dd. 23 Maart 1873; Syah, Brief van den Sultan aan den Gouvernements-Commissaris, dd. 25 Maart 1873.

[23] B.G. Buzan, O. Wæver & J.H. de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis (London, Lynne Riener Publishers, 1998); T. Balzacq et al., Securitization Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve (Oxon, Routledge, 2011) 1-30; P. D. Williams et al., Security Studies: An Introduction (Oxon,

Routledge, 2013) 63-76; J. L. Austin, How to do things with words (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1975); J. Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (London, Verso, 2010); M. Walzer,

Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations (New York, Basic Books, 2006); S. Leith, You talkin’ to me? Rhetoric from Aristotle to Obama (London, Profile Books, 2012); K. Parry, ‘Images of Liberation? Visual framing, humanitarianism and British press photography during the 2003

Iraq invasion’, in: Media, Culture & Society 33 (8) (2011) 1185-1201; J. Huysmans, ‘What’s in an act? On

security speech acts and little security nothings’, in: Security Dialogue 42 (4-5) (2011) 371-383.

[24] Balzacq, Securitization Theory, 3.

[25] Buzan, Wæver & De Wilde, Security, 21.

[26] Ibidem, 23-24.

[27] Ibidem.

[28] Ibidem.

[29] Ibidem, 26: ‘the process of securitisation is what in language theory is called a speech act’.

[30] According to Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde rhetoric is the distinguishing feature of securitisation.

[31] Williams & Paul, Security Studies, 72-73.

[32] Austin, How to do things with words, 6.

[33] Huysmans, ‘What’s in an act?’, 373.

[34] Buzan, Wæver & De Wilde, Security, 25: ‘to study securitisation is to study discourse and political constellations.’

[35] Ibidem, 32.

[36] Austin, How to do things with words, 26; Buzan, Wæver & De Wilde, Security, 33.

[37] Buzan, Wæver & De Wilde, Security, 25.

[38] For a detailed explanation of the notion of ‘existential threat’ and the elements ‘referent object’ and ‘securitising actor’ see Buzan, Wæver & De Wilde, Security, 21-23, 33-42.

[39] Buzan, Wæver & De Wilde, Security, 35.

[40] Nieuwenhuijzen, Oorlogsmanifest.

[41] Nieuwenhuijzen consequently send the manifesto to the consulates of the Western powers residing in Singapore. F.N. Nieuwenhuijzen, March 26 letter to Governor General Loudon.

[42] Nieuwenhuijzen, Oorlogsmanifest: ‘Verklaart uit kracht van de magt en bevoegdheid, aan hem door de Regering van Nederlandsch Indië verleend, in naam van die Regering, den oorlog aan den Sultan van Atjeh.’

[43] Nieuwenhuijzen, Oorlogsmanifest: ‘…de eischen van hare eigene veiligheid in noordelijk Sumatra….’ Moreover, Nieuwenhuijzen mentions the Acehnese hostile attitude and the Sultan’s disloyalty, perceived preparations for war, and his reluctance, indifference, and inability to restore peace and order.

[44] Loudon, Brief van 14 Maart 1873.

[45] Loudon, Instructie voor den Gouvernements-Commissaris voor Atjeh.

[46] Buzan, Wæver & De Wilde, Security, 36.

[47] Loudon, Brief van 25 Februarij 1873

[48] Loudon, Brief van 4 Maart 1873.

[49] Loudon, Brief van 4 Maart 1873.

[50] Loudon, Brief van 25 Februarij 1873.

[51] Loudon, Brief van 14 Maart 1873.

[52] Loudon, Brief van 25 Februarij 1873.

[53] Butler, Frames of War, xi.

[54] Parry, ‘Images of Liberation?’, 1188.

[55] Parry, ‘Images of Liberation?’, 1189. The societal level is what Parry calls ‘the broader context of a chosen period of time’.

[56] J.C. Boogman, ‘Achtergronden en algemene tendenties van het buitenlands beleid van Nederland en België in het midden van de 19e eeuw’, in: Bijdragen en Mededelingen van het Historisch Genootschap 76 (Utrecht, 1962) 43-73; M. Kuitenbrouwer, ‘Het imperialisme-debat in de Nederlandse geschiedschrijving’, in: BMGN Low Countries Historical Review 113 (1998) (1) 56-73; E. Locher-Scholten, Sumatran Sultanate and Colonial State: Jambi and the Rise of Dutch Imperialism, 1830-1907 (Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2004).

[57] Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars, 59.

[58] Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars.

[59] For a detailed explanation of the legalist paradigm see M. Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars, 61-62.

[60] E. Locher-Scholten, Sumatran Sultanate and Colonial State.

[61] À Campo as cited in Locher-Scholten, Sumatran Sultanate and Colonial State, 26.

[62] Loudon, Brief van 25 Februarij 1873; Loudon, Brief van 4 Maart 1873.

[63] Loudon, Brief van 4 Maart 1873, 1a. R. no. 14, geheim.

[64] Nieuwenhuijzen, Oorlogsmanifest.

[65] Loudon, Brief van 25 Februarij 1873.

[66] Leith, You talkin’ to me?, 1.

[67] Ibidem, 43.

[68] All documents are written in the grand style, lacking any form of humour, and deficient of figurative speech. The only difference between the Oorlogsmanifest and the other documents is that the manifesto of war is written in the past tense, except for the actual declaration of war in the last sentence, and containing a certain rhythm by reciting the consecutive arguments for war. See Leith, You talkin' to me?, 2012, 117-113 for an exposition on style.

[69] Leith, You talkin’ to me?, 47. See pages 45-77 for an excellent overview of the three parts of rhetoric.

[70] Ibidem.

[71] Ibidem.

[72] Ibidem, 66.

[73] Ibidem, 82-83. For an overview of the proposed scheme of a speech see pages 88-106.

[74] Ibidem, 82.

[75] F.N. Nieuwenhijzen, Brief van den Gouvernements-Commissaris aan den Sultan van Atjeh, dd. 22 Maart 1873.

[76] Nieuwenhuijzen, Oorlogsmanifest.

[77] Ibidem.

[78] Ibidem.

[79] Ibidem.

[80] Nevertheless, in his February 25 letter Loudon emphasizes his authority to convene an extraordinary meeting of the Council of the Dutch East Indies and to decide upon the course of action against Aceh.

[81] Loudon, Brief van 25 Februarij 1873.

[82] Ibidem.

[83] Loudon, Brief van 4 Maart 1873.

[84] Loudon, Brief van 25 Februarij 1873.