In 1995, on a dreary U.S. Air Force base in Dayton, Ohio, the agreement that should create peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina was signed.[1] The air force base had none of the luxuries of more pleasurable venues such as Camp David, but that was by design. Dayton, as Richard Holbrooke, the American envoy, later wrote, was: ‘the Big Bang approach to negotiations: lock everyone up until they reach agreement’.[2] The Dayton approach delivered in the short term. There was an agreement, and it ended the hot war. But it did not deliver peace. The agreement locked three warring ethnic groups in one country, separated them geographically, and introduced a mechanism to police the separation and continue to work on lasting peace.

A EUFOR Operation Althea exercise. Althea has a mandate to support Bosnia and Herzegovina and help maintain a safe and secure environment. Photo European External Action Service

Security sector reform (SSR) was part of the Dayton Agreements. The European Union was eventually given a leading role in this process, but more than twenty-five years after Dayton the security sector reform is still ‘ongoing’, a euphemism for almost complete standstill. This article takes a fresh look at this stasis by applying a new empirical framework. It assesses what the status of SSR is using a method developed by the The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (HCSS).[3] It is well-known that efforts by the international community to promote stability in fragile states through SSR have yielded mixed results. In its report The Good, the Bad and the Ugly HCSS offers an alternative approach to understanding the potential contribution of the security sector to stability. By applying this alternative way of understanding SSR to Bosnia and Herzegovina we hope to create fresh ideas to interpret the ongoing stasis, which it should be well understood, is not merely characterised by inactivity. There are tensions that are just below the surface and may occasionally flare up, as happened late October, prompted by the suggestion of Bosnian Serb separatist leadership to undo joint key state institutions.[4] A lot needs to be done to prevent the country from sliding into a hot war again. We also hope that by presenting the methodology in some detail it will become part of the analytical toolbox of militaries and ministries of foreign affairs.

Methodology

For this article we applied the methodology employed by HCSS in its report The Good, The Bad and the Ugly,[5] which presents an analytical framework and three case studies (Liberia, Tunisia and Nigeria). We have applied the same methodology to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

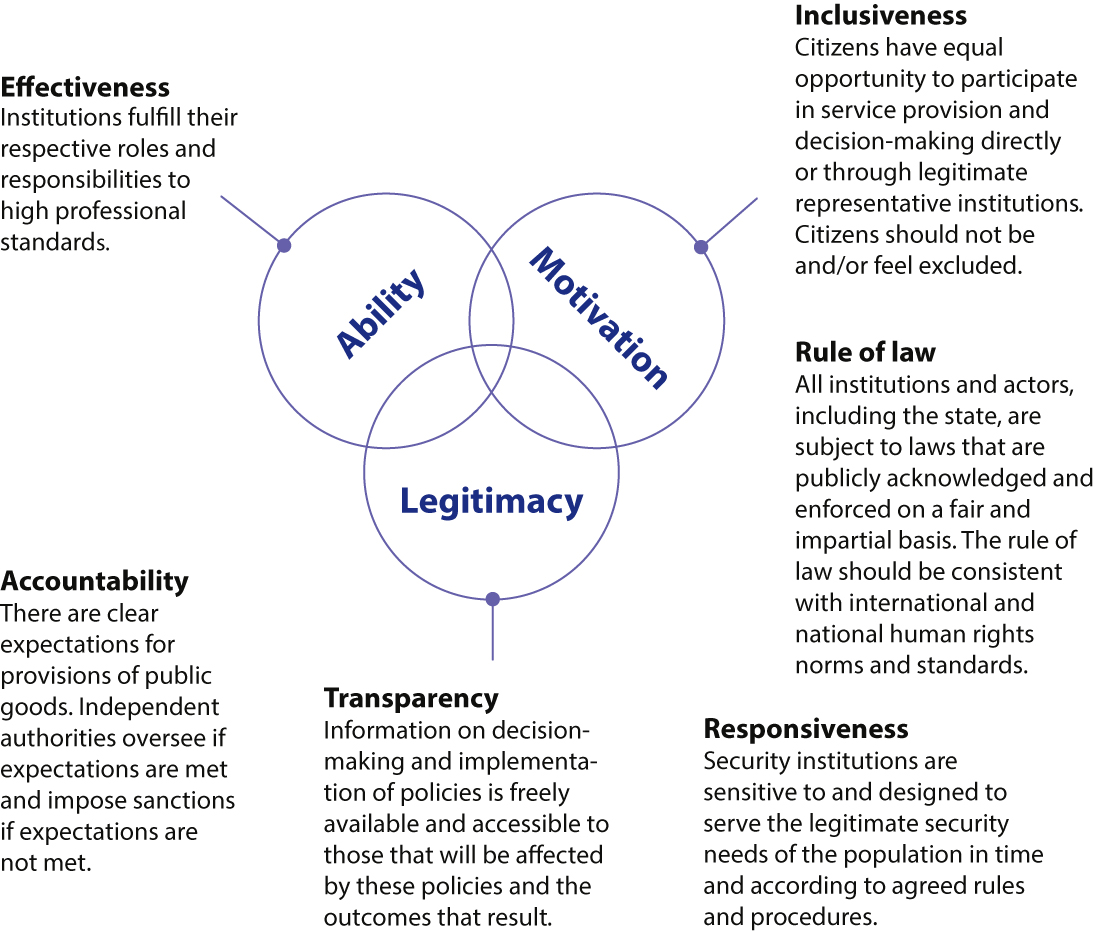

This methodology does not only assess the potential strength of the security sector by assessing the available organizations and budgets but it also focuses on softer variables, thereby implicitly stating that hard factors such as budgets and personnel are not the only relevant factors. What is important in security sector reform (as reflected in the methodology) is that a country has the values and the will to establish a functioning security sector that is rooted in the rule of law and accepted by all relevant parties. Only then will real and meaningful change take place. The assessment methodology looks at the ‘hardware’ (which it calls ability) but most of the indicators measure either legitimacy or motivation. As shown in Figure 1, these three characteristics in turn rest upon six principles of good governance: effectiveness, inclusiveness, rule of law, accountability, transparency, and responsiveness. The full overview of characteristics and their operationalization is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1 The characteristics and principles to assess the contribution of the security sector to contribute to stability

The assessment of the three main characteristics rests on the combined assessment of eight indicators. In the original HCSS method these indicators are based on standard indexes or ratios. For example, the characteristic ‘ability’, which measures the extent to which the security sector is able to ‘maintain internal security’,[6] rests on an assessment of the institutional strength of the security sector. This is measured by the proxy indicator ‘number of policemen per 100,000 inhabitants’. The degree to which the governmental security apparatus controls the use of force is measured by one of the indicators of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index, the Monopoly on the Use of Force indicator.[7] Based on these measurements each characteristic is assessed on a 5-item scale (low – medium low – medium – medium high – high).

HIER INVOEGEN: Figuur 2

Bijschrift: Figure 2 Characteristics (variables) and operationalization in the HCSS analysis

While the proxy indicators are in themselves good measures that capture the empirical situation (most of them have been developed by NGOs and specialists with experience in their fields), we also conducted an extensive analysis of literature on Bosnia and Herzegovina to put these indicators in the context of recent research, so as to refine our judgement. So, while this study replicates the HCSS method, the literature review is our own.

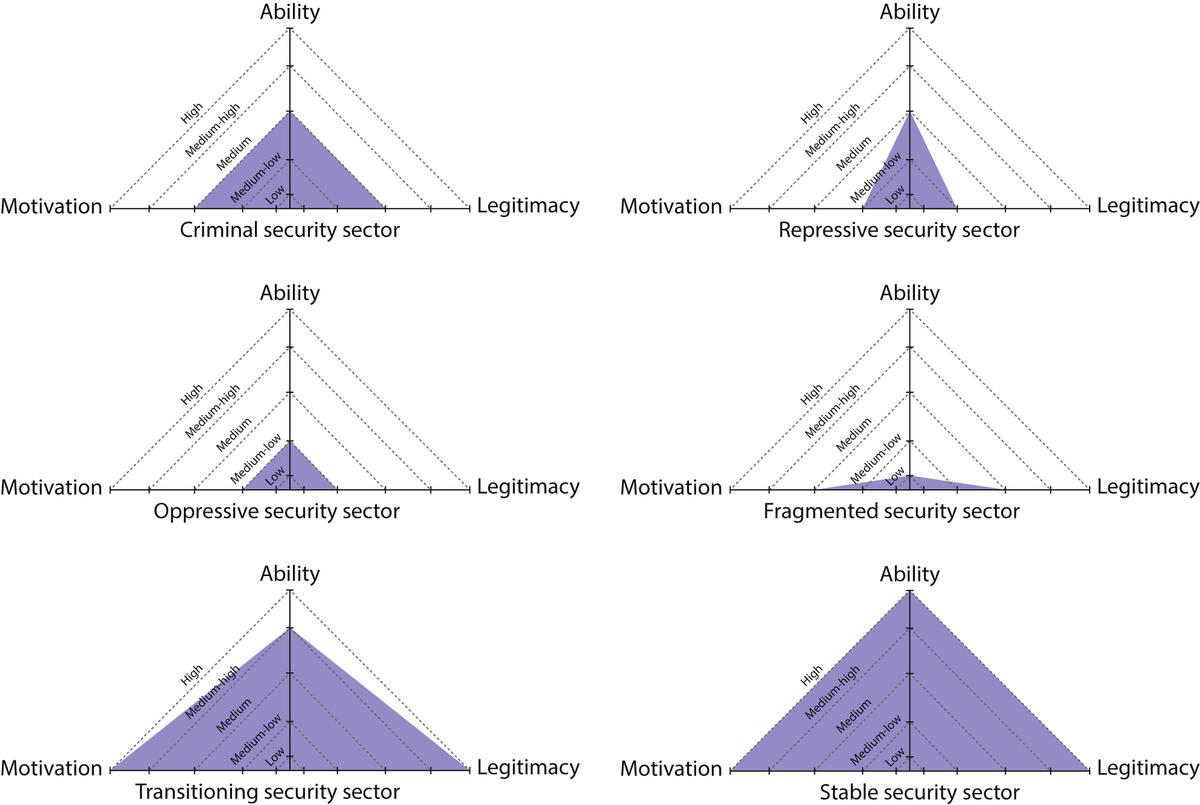

The analysis results in a set of typologies of security sectors, based on the variation of the three main characteristics, ability, motivation and legitimacy. Of course, the number of theoretically possible combinations of varieties of the three characteristics is far greater than the limited number the methodology presents (in Figure 3), but a lot of the possible combinations were rejected on the basis of literature analysis, empirical unlikeliness, and other factors.[8]

Figure 3 Typologies of security sectors[9]

These typologies capture the state of the security sector. Apart from the stable security sector, each typology is characterized by a specific way in which stability is undermined. The HCSS report gives the following descriptions of each typology:[10]

- The criminal security sector promotes the proliferation of non-state actors and criminal networks that create and stimulate insecurity and conflict. It does not prioritize protection of the population and instead financially profits from trading licit and illicit goods.

- The repressive security sector exclusively protects the regime and rules by coercion rather than by consent. The population is subject to state-sponsored violence without having the opportunity to scrutinize the security sector’s performance.

- The oppressive security sector exclusively protects the regime, but is unable to control security actors and maintain a monopoly on the use of force. State-sponsored security actors operate autonomously and subject the population to indiscriminate use of force.

- The fragmented security sector supports and/or directly engages with informal security actors. Security provision is decentralized and as a result the security sector does not control how force is used.

- The transitioning security sector is relatively stable but not resilient, because it is governed by old regime structures that are not adept at responding to contemporary security issues and/or located in a volatile region.

Evidently, each typology asks for a different SSR policy approach.

Assessment of Bosnia and Herzegovina

When assessing security sector reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina, how does the country score on the three main characteristics? The following section explains the performance of Bosnia’s security sector on its ability, motivation, and legitimacy.

Assessment of ability

Bosnia’s security sector scores medium on ability.[11] Ability derives partly from possessing sufficient financial, human and material resources and intelligence capacity (potential ability) and partly from having the capability to convert these available resources into security provision proficiency (actual ability).

In terms of financial resources, Bosnia has made progress towards a more sustainable security sector. For years after the Dayton Agreement the high costs of maintaining parallel security structures following ethnic lines were effectively bankrupting the Bosnian state. Subsequent reforms have brought expenditures more in line with other countries in the region. However, the weak state of the economy and persistent reliance on international funds continue to put pressure on the security sector. In addition, the relatively low salaries in the sector contribute to high levels of corruption.[12]

The cost reduction was realised mainly by significantly downsizing the number of personnel in the security sector. The security sector personnel were vetted after the war in order to strip the sector of those who committed war crimes and human rights abuses.[13] In order to improve the quality of the human resources in the sector, the international community has supported various training programmes and deployed many experts, but with mixed results.[14] In its response to the influx of refugees and migrants in 2018 and 2019, the Border Police has recently been shown to be understaffed.[15]

Moreover, the Bosnian security sector is lacking in material resources, such as infrastructure and equipment, which is shown, for example, in the under-resourced investigative and prosecutorial agencies[16] and Border Police,[17] as well as in the overcrowded prison system.[18] As Rosga noted,[19] contrary to internationally held beliefs, a lack of equipment and resources is regarded by some within the Bosnian police as a more urgent problem than inter-ethnic tensions.

With regard to its intelligence capacities, Bosnia was for a long time undermined by the existence of separate security services under the control of various political parties. A notable success was the introduction in 2004 (essentially pushed through by the High Representative)[20] of a state-wide Law on Intelligence and Security Agency and the creation of a single Intelligence and Security Agency. However, this central body is not yet very effective.[21] Also, the sharing and exchange of intelligence throughout the Bosnian state is still very limited.[22]

Furthermore, it is noted here that - as an overall challenge for Bosnia regarding the four types of resources - the multiple levels of government make for a very costly and inefficient use of the already limited resources available.[23] This hinders the transfer of potential ability into actual ability.

American personnel visit leaders and cadets at the AFBiH Training and Doctrine Command. In contrast to how the Bosnian public views the police, military institutions are seen as trustworthy. Photo U.S. Air National Guard, Sarah M. McClanahan

Regarding the actual ability or effectiveness of the Bosnian security sector, the state’s monopoly on the use of force throughout its territory has in principle been established. The security situation in Bosnia is relatively stable and has normalised in important respects. That in itself is a significant achievement after the bloody war in the early nineties. But the continued complexity of horizontally and vertically divided competences and persistent politicisation continues to obstruct the ability of Bosnia to effectively govern and provide security for all its citizens.[24] In this respect, it may also be noted that the main reform effort by the international community in Bosnia has been conventionally state-centric, as opposed to venturing from a broader understanding of human security.[25] In the view of the Bosnian public, especially organised crime, corruption and high-profile (political) incidents are the main factors underlying continued feelings of insecurity, that may vary across regions and cantons.[26] Lastly, recent developments as to the actual ability of the Bosnian security sector show a downward trend. The Fragile States Index notes an ‘elevated warning’ for Bosnia in its 2020 report.[27]

Assessment of motivation

Bosnia scores medium on motivation. Following the Dayton Agreement and subsequent agreements, the international community tried to build up a multi-ethnic and inclusive security sector in Bosnia, motivated to protect all its citizens on an equal basis.[28] However, Bosnia’s medium score on motivation raises doubts to what extent the above-mentioned goal has been met.[29]

With regard to the police, it proved first of all that it was not feasible to have a unified law enforcement agency, calling into question the institutional motivation to protect the whole population. Bosnia has several police agencies with divergent jurisdictions and responsibilities.[30] The absence of a nationwide law enforcement agency appears to erode the good governance principle of inclusiveness. A notable exception since its inception in 2004 is the State Investigation and Protection Agency (SIPA), with a mandate across Bosnian territory, but its mandate is limited to serious crimes such as terrorism and war crimes. That being said, it could play the role of precursor to an eventual overall nationwide law enforcement agency.

In addition to the above-mentioned institutional challenges, the international community failed to fully assess the impact that Bosnia’s parallel power structures (based on nationalism and along ethnic lines) would have on the stabilisation of Bosnia.[31] For example, the appointment of senior security sector officials in Bosnia is often politically motivated, with appointees guided by the interests of their patrons rather than the security interests of the population.[32] At the lower ranks, police officers were meant to be deployed in areas with another ethnic composition than their own. However, many police officers decided to stay in their original homes, sometimes citing security reasons and often commuting considerable distances.[33] The fact that police officers do not live in the community whose security they are supposed to protect further jeopardises the goal of a multi-ethnic police force and raises questions about their individual motivation to protect all different ethnic groups.[34]

The security sector must be inclusive and offer equal opportunities for all its citizens to participate in the provision of security.[35] At first sight the ethnic breakdown of the members of the since 2005 unified Armed Forces of Bosnia-Herzegovina (AFBiH) indicates that all ethnic groups have an equal opportunity to participate.[36] However, most of the units are not ethnically mixed; Bosniak soldiers, for example, are enlisted in a Bosniak battalion in an area with an ethnic Bosniak population. This means that the effect or impact that a multi-ethnic character of the AFBiH could have is seriously hampered by the deployment structure.

On the other hand, Bosnia has made significant progress in promoting the inclusion of women in the security sector, partly because of a mandated quota of 10 per cent female police.[37] However, in 2010 the percentage of police women at the Ministry of Interior of Republika Srpska (RS) was 6.71 per cent and 8.20 per cent in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) Ministry of the Interior.[38] At the same time, remarkable progress has been made with regard to the inclusion of women in the AFBiH. There has been a gradual increase from 4.7 per cent in 2007 to 7.61 per cent in 2020, with women represented at all levels of leadership and command ranging from private to colonel. However, these gains made in terms of the inclusion of women might be at risk in case of a shift in political winds.[39]

Regarding the rule of law, the goal of the Bosnian police system to be fully capable of upholding rule of law standards remains far from being accomplished, mainly because of the earlier mentioned patchy institutional structure.[40] Moreover, this fragmented structure entails a lack of coordination among the different levels of government and relevant judicial institutions.[41] The legal framework has not been harmonised on the different levels (state, entities, Brčko District), resulting in a lack of transparency and the failure to uphold equality before the law.[42] Criminal and corrupt officials regularly exploit Bosnia’s piecemeal police system, resulting in impunity simply by going to another jurisdiction.[43]

Remarkable progress has been made with regard to the inclusion of women in the AFBiH. Photo UN Women Europe and Central Asia

The above-mentioned flaws are reflected in the public perception, with more than half of Bosnia’s citizens stating that corruption is on the rise.[44] On the individual level, the presence of corruption among police officers in Bosnia[45] as well as violations of human rights should be noted.[46] Sometimes corruption within the police is linked to organised crime.[47] In contrast to how the public views the police, military institutions are seen as trustworthy.[48]

Assessment of legitimacy

When analysing the legitimacy of the security sector according to the HCSS Security Sector Assessment Framework (SSAF), Bosnia scores medium.[49] The main elements of legitimacy are defined by HCSS as accountability towards independent oversight institutions, transparency in the decision-making procedures and responsiveness towards the security concerns of the population.

To assess these three principles, the recent literature on security sector reform in Bosnia was analysed. There have recently been a number of evaluations of SSR in Bosnia[50] from which the conclusion can be drawn that SSR has not been a great success in Bosnia. The main problem in Bosnia emerging from these evaluations is the existence of parallel power structures alongside the official structures, as described clearly by Dziedzic.[51] This dynamic affects all parts of Bosnia’s security sector and impacts the good governance principles of accountability and transparency immediately and severely. Several Croatian, Bosniak and Serbian power groups are able to influence formal decision-making, while being neither accountable nor transparent about their (covert) activities in the security sector. The lack of cooperation between institutions and the active obstruction and counteracting of internationally demanded SSR activities also hinders accountability and transparency. Parallel security institutions for each ethnic community, lack of trust, hidden agendas, lack of local ownership of internationally enforced reforms and nepotism are major problems in this respect. Transparency International[52] points out that Bosnia suffers repeatedly from instances of state capture, where networks of oligarchs, politicians and law enforcement officials conspire to use their formal powers to protect and further their private economic and criminal interests.

A case in point regarding accountability and transparency is the reform of the judiciary. The reform of the judiciary started slow and also here the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska set out to develop separate institutions. The reform process focused on creating state level judiciary institutions (courts, laws, prisons), but the RS has sought to prevent much of this centralisation of the judiciary. In 2019, an EU-commissioned report[53] on the judiciary judged it to be fundamentally flawed. The report noted that reforms that were enacted to address issues have actually become part of the problem themselves. New institutions that were meant to enhance oversight of the sector, such as the office of the Ombudsman and the High Level Prosecutorial Council, are deeply politicised and lack independence.

In addition, in 2020 the European Commission[54] indicated that the political deadlock resulting from the struggle between the different power structures undermines the functional operation (or even formation) of the Parliamentary joint committees on defence and security and on the security and intelligence agency. This influences accountability and transparency directly, as the Parliamentary Assembly and its committees evidently have a crucial role in the civilian oversight of the Bosnian security sector.

The problematic accountability and transparency of the Bosnian security sector naturally has an effect on its responsiveness: it hardly seems possible that a government that lacks sufficient accountability and transparency will show a high responsiveness towards the security concerns of the (entire) population, made up of three competing ethnic groups.

Bosnian army personnel train with American troops. Bosnia has developed a relatively stable security environment, but the situation is still fragile. Photo U.S. Air Force, William Greer

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE),[55] which leads an SSR mission in Bosnia, states that the security and justice reforms in Bosnia have been highly politicised and framed primarily as a State building instrument, instead of being a practical and technical reform agenda. In addition, the OSCE finds that the inclusion of civil society, women and youth in this respect is lacking. This undermines the responsiveness of the security sector, in which the legitimate security needs of the population are not being served adequately.

The same dynamic affects the judiciary: the judiciary consistently fails to address the security needs of the general population and instead functions as the shield for political patronage networks. Lastly, the questionable responsiveness of the Bosnian security sector is also clearly reflected in the public perception, as noted above.

Analysis of the security sector of Bosnia and Herzegovina

If the HCSS framework is applied to Bosnia and Herzegovina, the following picture emerges. Quantitative analysis of the indicators pertaining to ability, motivation, and legitimacy resulted in medium scores for all three characteristics and the subsequent categorization of Bosnia as having a security sector of the criminal type. HCSS defines a criminal security sector as follows: ‘The criminal security sector faces systematic challenge from organized criminal groups that have direct or indirect ties to the security sector. This dynamic is deeply imbedded into the structure and functioning of the security sector’.[56] The ideal type of security sector is the ‘stable’ type, an effective security sector that is able to protect the population (and that scores ‘high’ on ability, motivation, and legitimacy). It is clear that Bosnia and Herzegovina is far removed from that ideal, and is also not transitioning in that direction.[57]

In terms of ability, Bosnia was shown to have made some positive steps in providing adequate resources for its security sector since the Dayton Agreement, but is still lacking in important respects and hindered by inefficiency. Whereas Bosnia has developed a relatively stable security environment, the situation is still fragile and has recently shown a worrisome downward trend.

Regarding motivation, it was demonstrated that the goal of creating an inclusive security sector has still not been met. Positive developments have been made in promoting equal opportunities for women in the security sector, but continued resistance by the three ethnic power structures to centralisation and harmonisation means that the security sector still suffers greatly from fragmentation in its operation, most notably in the police department.

The existence of parallel power structures was also pointed out as the main problem affecting the legitimacy of the Bosnian security sector. Politicisation, high levels of corruption and deadlock between the three rival structures were shown to burden all parts of the security sector. The accountability, transparency and responsiveness of the Bosnian security sector leave a lot to be desired.

As noted in the HCSS framework, the interaction between the three characteristics ability, motivation and legitimacy is crucial to understand Bosnia’s security sector. It appears that the crux lies in the lacking motivation of the three rival Bosnian elites to build up a nationwide security sector with both the ability and legitimacy to serve the security needs of all Bosnian citizens to a high standard. This same dynamic of competing parallel power structures makes for human security taking a backseat to state security, as highlighted by the lacklustre performance of especially the police department, which ultimately is the first line to provide real security to Bosnian citizens.

To resume, what stands out most is that applying the HCSS lens identifies Bosnia and Herzegovina as having a security sector of the criminal type. This contrasts with the common view and treatment of Bosnia by the EU and the broader international community as having a transitioning security sector.

Conclusion

The discussion on security sector reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina has always been implicitly based on the notion of transformation. The very terminology, security sector reform, implies an attempt to move from a bad situation to a good one, or at least a more acceptable one. This is a rather fundamental assumption, based on the predominantly western notion that societies are in constant movement towards a better situation. Stagnation as a goal or a satisfactory state of affairs is not compatible with the idealism that underlies thinking in the liberal inter-governmentalist school of international relations, on which international interventions like the one in Bosnia and Herzegovina are based. In Bosnia and Herzegovina we see that ethnic separation and criminal capture have created a situation in which stagnation favours political, ethnic and criminal elites. It is needless to say that once the elites that have to create change have a vested interest in stagnation, much hope is lost and deeply-rooted stability gets out of reach.

The main conclusion is that security sector reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina cannot only focus on the security sector. The state of the security sector is a consequence of the way political and social elites have been allowed to run the state of affairs. Security sector reform is thus necessarily a broad activity that should focus not only on the organisations and means of security (the ability in these terms) but also on the motivation and legitimacy of reform. That requires a comprehensive approach in which political, social, military and constabulary knowledge are integrated, and in which a variety of partners (ministries of foreign affairs and defence, NGOs) take concerted action.

[1] For the full text, see: https://peacemaker.un.org/bosniadaytonagreement95.

[2] Richard Holbrooke, To End a War (New York and Toronto, Modern Library Paperback, 1999) 232.

[3] The authors want to acknowledge the work of the colleagues of 1Civil Military Interaction Command who executed the quantitative analysis: maj(R) Sander Agterhuis LL.M, maj(R) dr. Pépin Cabo, tltn(R) René Kersten, maj(R) Tom Kievit MA, and Eltn(R) Paul Neelissen MSc MA. Their work will be separately published by 1Civil Military Interaction Command later on. We also acknowledge the original work of the The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (our study replicates their methodology) and in particular the good cooperation with Dorith Kool MSc.

[4] ‘Bosnia’s peace deal is at risk of unraveling, warns envoy’, CNN, 2 November 2021. See: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/11/02/europe/bosnia-peace-deal-at-risk-envoy-intl/index.html.

[5] Dorith Kool and Tim Sweijs (main authors), The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, A Framework to Assess Security Sectors’ Potential Contribution to Stability (The Hague, HCSS, 2020).

[6] Kool and Sweijs, The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, 10.

[7] The Bertelsmann Transformation Index measures transformation to democracy with a large number of indicators. See: http://bti-project.org/en. On the specific indicator ‘Monopoly on the Use of Force’: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2020 Codebook for Country Assessments (2020) 16. See: https://bti-project.org/fileadmin/api/content/en/downloads/codebooks/BTI_2020_Codebook.pdf.

[8] For an explanation, see: Kool and Sweijs, The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, 40.

[9] Ibidem, 14.

[10] Ibidem, 41ff.

[11] Bosnia scores 2.38 on the proxy indicator ‘number of policemen’ (UNODC Crime Trends Survey) and 4.1 on the proxy indicator ‘monopoly on the use of force’ (Bertelsmann Transformation Index). Bosnia’s final ability score is 6.49, putting Bosnia in the 63rd percentile.

[12] M. Caparini, ‘Security sector reform in the Western Balkans’, in: SIPRI Yearbook 2004: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security (2004); B. Marijan, Assessing the Impact of Orthodox Security Sector Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina, (Geneva, CSG Papers, 2016) 18, 31.

[13] Marijan, Assessing the Impact of Orthodox Security Sector Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 11, 16.

[14] Ibidem, 31, 41; A. Kudlenko, ‘Security Sector Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Case Study of the Europeanization of the Western Balkans’, in: Südosteuropa 65 (2017) (1) 71.

[15] European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document. Bosnia and Herzegovina 2020 Report. Communication on EU Enlargement Policy (2020).

[16] M. Dziedzic, ‘The Dayton Accords and Bosnia’s parallel power structures: impact and security implications’, in: Militaire Spectator 189 (2020) (12) 633.

[17] European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document. Bosnia and Herzegovina 2020 Report.

[18] Marijan, Assessing the Impact of Orthodox Security Sector Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 17.

[19] A. Rosga, ‘The Bosnian police, multi-ethnic democracy, and the race of “European civilization”’, in: Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (2010) (4) 688.

[20] The position of High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina was created in the Dayton Agreement to oversee its implementation, under pressure from the international community. The High Representative holds vast (veto) powers over Bosnian politics.

[21] Kudlenko, ‘Security Sector Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, 72.

[22] European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document. Bosnia and Herzegovina 2020 Report, page 36.

[23] BTI, Country Report Bosnia and Herzegovina (2020) 33.

[24] BTI , Country Report Bosnia and Herzegovina, 30; Marijan, Assessing the Impact of Orthodox Security Sector Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 27.

[25] Marijan, Assessing the Impact of Orthodox Security Sector Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 27.

[26] Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2020. Bosnia and Herzegovina (2020) 13; Marijan, Assessing the Impact of Orthodox Security Sector Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 32.

[27] Fund for Peace, Fragile States Index Annual Report 2020 (2020) 7.

[28] A. Mayer-Rieckh, Dealing with the Past in Security Sector Reform (Geneva, DCAF, 2013).

[29] Bosnia scores 2.71 on the proxy indicator ‘Political Rights and Civil Liberties Ranking averaged’ (Freedom House), 3.64 on the proxy indicator ‘Equal Protection index’ and 3.13 on the proxy indicator ‘Rule of Law index’. Bosnia’s final motivation score is 9.53, putting Bosnia in the 57th percentile.

[30] Kudlenko, ‘Security Sector Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina’.

[31] Dziedzic, ‘The Dayton Accords and Bosnia’s parallel power structures’.

[32] V. Azinović, ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Nexus with Islamist Extremism’, DPC Bosnia Daily (2015) 12.

[33] Mayer-Rieckh, Dealing with the Past in Security Sector Reform, 41.

[34] Rosga, ‘The Bosnian police, multi-ethnic democracy, and the race of “European civilization”’, 686.

[35] Kool and Sweijs, The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, 11.

[36] Ethnic representation within the AFBiH is set at 45.90 per cent Bosniak, 33.60 per cent Serb, 19.80 per cent Croat and 0.70 per cent other (2011 figures provided by the BiH Ministry of Defense and quoted in ‘Marijan, Assessing the Impact of Orthodox Security Sector Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 28).

[37] Rosga, ‘The Bosnian police, multi-ethnic democracy, and the race of “European civilization”’, 686.

[38] Figures provided by both Ministries in 2010, via source known by the authors.

[39] High Representative, Fifty-eighth report of the High Representative for Implementation of the Peace Agreement on Bosnia and Herzegovina (OHR, 2020), 1.

[40] European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document. Bosnia and Herzegovina 2020 Report, page 5.

[41] BTI, Country Report Bosnia and Herzegovina, 7, 15.

[42] DCAF, Bosnia and Herzegovina SSR Background Note (Geneva, DCAF, 2017).

[43] J. Ahic (2007), ‘Bosnia’s Security Sector Reform – State Border Service of BH as an efficient Border Management Agency’, in: A.H. Ebnöther, P.H. Fluri and P. Jurekovic (eds.), Security Sector Governance in the Western Balkans: Self-Assessment Studies on Defence, Intelligence, Police and Border Management Reform (Vienna and Geneva, 2007) 377.

[44] UNODC, Corruption in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Bribery as Experienced by the Population (2011) 9.

[45] UNODC, Corruption in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 8, 12.

[46] U.S. State Department, Bosnia And Herzegovina 2019 Human Rights Report (2019), 2.

[47] Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2020. Bosnia and Herzegovina.

[48] Marijan, Assessing the Impact of Orthodox Security Sector Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 32.

[49] Bosnia scores 4.1 on accountability (approximated by the V-DEM Varieties of Democracy accountability index), 2.57 on transparency (approximated by the State Legitimacy scale of the Failed State Index) and 2.96 on responsiveness (approximated by the State apparatus scale of the Failed State Index).

[50] OSCE, Security Sector Governance and Reform (SSG/R) (2020); Dziedzic, ‘The Dayton Accords and Bosnia’s parallel power structures’; A.E. Juncos, ‘EU security sector reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Reform or resist?’, in: Contemporary Security Policy 39 (2018) (1); Kudlenko, ‘Security Sector Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina’; Marijan, Assessing the Impact of Orthodox Security Sector Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

[51] Dziedzic, ‘The Dayton Accords and Bosnia’s parallel power structures’.

[52] Transparency International, Examining State Capture: Undue Influence on Law-Making and the Judiciary in the Western Balkans and Turkey (2020).

[53] European Commission, Expert Report on Rule of Law issues in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2019).

[54] European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document. Bosnia and Herzegovina 2020 Report.

[55] OSCE, Security Sector Governance and Reform (SSG/R), 1.

[56] Kool and Sweijs, The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, 43.

[57] For a complete overview of all typologies see: Kool and Sweijs, The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, 42.