In September 2017, joint Russian and Belarusian forces participated in Zapad 2017, a large military exercise that took place in Russia’s Western Military District and Belarusian western territories. In the months leading up to September, Western media published increasingly concerned articles about this display of military power near the borders of Poland and the Baltic states, with estimates of up to 100,000 participating troops. The concern showed an uncertainty among European nations about their current security environment. In a way, Russia encouraged this uneasiness, which indicates that Zapad 2017 not only served as a display of conventional military capabilities, but had an aspect of hybrid warfare to it as well. In this article we analyse what implications Russia’s Zapad 2017 military exercise has on European security strategy?

T.H.F. Herbert BA*

In order to find the answer to the question above, first an overview of Zapad 2017 will be given and its possible propagandistic aspect will be indicated. Then, the reactions of European nations on Zapad 2017 will be discussed and how these played into the hands of Russia’s information campaign. Next, the foundations of the Russian threat perception and its anti-Western narrative will be elaborated on. Zapad 2017 and its place in Russia’s foreign policy strategy will be explained, followed by a description of the security strategies of both the European Union (EU) and the Northern Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and how they responded to increased Russian assertiveness but ultimately failed to effectively deal with potential Russian aggression as well as counter the Kremlin’s information campaign. Lastly, some broader implications of Zapad 2017 will be described, followed by some suggestions on how Western nations should alter their security strategy.

While much has been written about the increased threat Russia poses to European security, opinions vary on how European nations could best improve their policies. As a result, Europe remains seemingly inapt to adequately respond to Russian exclusion from the rules-based order. This essay aims to provide clarity on how Zapad 2017 is an evident part of Russia’s strategy of hybrid warfare to affect Europe’s security certainty and what issues need to be addressed in order to counter it effectively.

The simulation game: Zapad 2017

In 2008 Russian armed forces reinitiated their practice of regular large-scale strategic exercises. The first of its kind, called Kavkaz 2008, took place in Russia’s Southern Military District, close to the Georgian border. Within a week after the official conclusion of the exercise, an estimated 40,000 Russian troops were engaged in a military operation on Georgian territory, only to be stopped five days later due to international pressure. Since then, similar military exercises have been planned and conducted annually.

This essay focuses on the large-scale exercise last year; Zapad 2017. Called after the Russian word for West, Zapad 2017 was the third time the exercise focused on Russia’s Western territories, preceded by Zapad 2009 and Zapad 2013. Like its predecessors, Zapad 2017 was a product of joint Russian and Belarusian forces. Typical of these exercises, which take place in Russia’s western Military District, is that the reported number of participating troops is much smaller than the actual number of personnel engaged. To illustrate, the Russian Ministry of Defence announced that a total of 12,700 troops would participate in Zapad 2017, while in reality more than three times as many troops are estimated to have been involved.[1] According to estimates from the Royal United Services Institute, around 60,000 to 70,000 Russian troops were active in Zapad 2017, 12,000 of which on Belarusian territory.[2] The fact that additional personnel is necessary to provide logistical support should be taken into consideration, which means that the number of involved personnel could be even higher.

Collage of the Russian Ministry of Defense joint strategic exercises West-2017 of the armed forces of the Union State of Russia and Belarus. Photo Mil.ru

It is likely that Russia deliberately releases incorrect numbers. In doing so it avoids the mandatory inviting of foreign observers, which is prescribed by paragraph 47.4 of the Vienna Document. This OSCE agreement, implemented to increase ‘confidence- and security-building measures’, requires participating states to invite foreign observers to military exercises when the number of participating troops equals or exceeds 13,000.[3] A look at the numbers of participating troops in Russia’s annual military exercises shows that the number of troops participating in the Central and Eastern Military Districts, where the Vienna Document is not applicable, match the amount reported beforehand. In contrast, the numbers concerning exercises in the Western and Southern Military Districts seem to be structurally underestimated or compartmentalised in smaller bits in order to avoid the requirements of the Vienna Document. While in 2017 no Russian officials have explicitly admitted to purposely underestimating the numbers, in 2008 General Yuri Netkachev acknowledged to reporters from the Russian newspaper Nezavisimaya Gazeta that the amount of estimated troops during Kavkaz 2008 was ‘officially lowered’ in order to avoid foreign observers.[4] As was previously pointed put, evidence suggests that this trick was used in 2017 as well. Belarus did, in fact, invite foreign observers, but the level of access to different parts of the exercise remains unclear.[5]

During Zapad 2017, the troops engaged in a simulated war scenario on Russian and Belarusian soil. The exercise was performed by ground troops, with support from reconnaissance units and special operations forces, air and airborne forces, air defence, and naval elements[6]. According to Russian news agency TASS the scenario of Zapad 2017 depicted ‘expanding operations by armed groups and international terrorist and separatist organizations enjoying external support’.[7] As described by TASS, the first phase of the exercise aimed to repel the hypothetical enemy’s offensive and to engage in an attack on its main forces, facilities and infrastructures. The second phase comprised defensive operations against intruders and a counter-offensive aimed at ‘the enemy’s complete defeat’. Central in this ‘military’ operation was the fictional country of Veyshnoria, which tried to penetrate Russian and Belarusian territory using illegal armed troops. In combatting Veyshnorian troops, Russia practised both asymmetric and conventional warfare. Yet, while Zapad 2017 started as a defensive exercise using anti-terrorist tactics, it quickly changed into a conventional operation focused at defeating an equally conventional and advanced enemy.[8] This strongly resembles what an operation against NATO armed forces would look like. As Boulègue explains: ‘[the] ‘Veyshnorian troops’ went from initially conducting lightly-equipped border incursions to launching massive air strikes and land attacks with tremendous fire power, air supremacy capabilities, submarines, and EW capabilities.’[9] Additionally, as was put forward by Maggie Tennis, ‘many of the drills featured defence operations against technologies that only the United States would possess, such as high-speed drones’.[10] As it turned out, Zapad 2017 looked a lot like a rehearsal for the response to an actual NATO intervention.

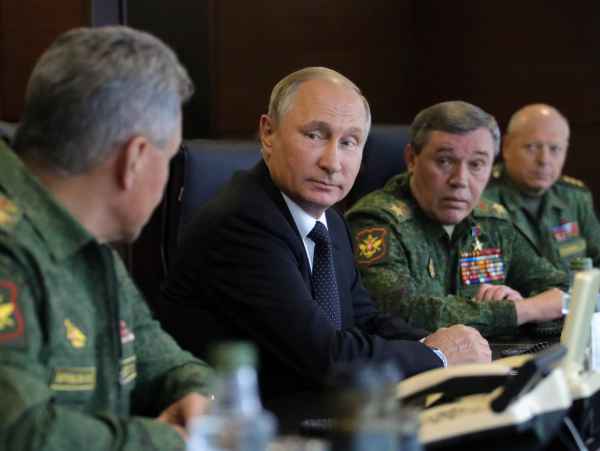

Russian President Vladimir Putin and military staff watch the Russia and Belarus joint strategic exercises Zapad 2017 on the Luzhsky range, 18 September 2017. Photo ANP/EPA/Sputnik/Kremlin Pool/M. Klimentyev

This led experts to believe that in Russia’s view, Zapad 2017 had propaganda as well as military value. The propagandistic aspect of the exercise would be matching a broader information campaign the Kremlin has been carrying out for years, the main goal being for Russia to be perceived as the natural leader in its sphere of influence as well as a global power that is able to oppose the West. Once described as ‘a long-term psychological war against the will and endurance of the West’, the campaign is composed of military incursions, threats and a substantial use of media propaganda.[11] Russia’s point of view is based on the idea that Western nations see themselves as victors of the Cold War and try to expand their alliance eastwards. Evidently, the collapse of the Soviet Union and subsequent weakening of Russia’s position as a global superpower is a particularly painful subject in current Russian discourse. Following this line of thought, Russia is only trying to protect its national interests and stay a respected world power, while being threatened by the hostile West. Jonathan Stevenson explains about Zapad 2017 that ‘the recent exercise reflects not only Moscow’s resentment of the West’s perceived attitude, but also its determination – reinforced by its assertiveness in Ukraine and Syria – to re-establish Russia as a great power with a well-defined sphere of interest’.[12] Taking this into consideration, it is most likely that Zapad 2017 was part of the Kremlin’s strategy to expand its power and influence at the expense of European security, in order to be perceived as a great power.

Between concerns and hysteria: the European response

How did European nations respond to Zapad 2017? In the wake of it, some observers voiced concerns about the scale of the exercise and the amount of troops involved. In June, the commander of U.S. troops in Europe expressed concerns about Zapad 2017 being located close to NATO borders. He stated that more troops would be sent to Eastern Europe.[13] Amongst the most vocal NATO countries was Poland, whose government proclaimed it would be watching the exercise most carefully.[14] Similar sentiments were heard in other European countries located close to Russia and familiar with Russian occupation, like the Baltic States.

In some instances Zapad 2017 was described as a ‘Trojan Horse’ through which Russia could launch an actual military operation, as had happened in Georgia in 2008.[15] While no seasoned expert really believed the scenario of Russia starting a military campaign to become reality, the media quickly jumped on the story. Estimates from NATO officials, who suspected that up to 100,000 troops could be taking part in Zapad 2017’s exercises, did not help curb the unrest either. The annual Russian exercises in its military districts were often forgotten. Mathieu Boulègue tried to calm the hysteria: ‘Zapad is a routine exercise, so there is no cause for alarm in the sense that Russia will stick to the scenario.’[16] Adding to this, an actual Russian invasion of the Baltic States would almost certainly ensure the escalation of the current situation and easily become the start of a real armed conflict between Russia and NATO. It is highly unlikely that Russia would even consider this plan of action.

Still, the overestimations of troops by European experts and media perfectly fit the scheme of the earlier mentioned Russian information campaign. When estimates of 100,000 Russian troops participating in Zapad 2017 were circulating in the Western media, Russian news outlets could not wait to call such concerns exaggerations created by anti-Russian ‘hysteria’, as did scholar Andrey Suzdaltsev, a political scientist and professor at the prestigious Higher School of Economics in Moskou.[17] In an article by TASS, the concerns were described as ‘stupidities’, told by Western media and NATO officials as part of a ‘psychological information-bombardment’.[18] Evidently, Russian authorities had wanted this to happen. By creating uncertainty in the European security environment, Russia encouraged the concerns and fears of Western nations, which they could then describe as hysterical and use to further discredit the West. Meanwhile, as Western countries voiced their concerns, Zapad became a source of amusement for Russian internet users. Memes and jokes about Veyshnoria were quickly circulating on Russian websites and even a Veyshnorian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ twitter account was created[19], all to suggest that the military exercise was just fun and games. In this sense, for Russia Zapad 2017 has proven to be quite successful; it has reinforced both Russia’s right to defend its sphere of influence, as well as its claim that NATO member states exaggerate the extent of Russia’s geopolitical aggression.

June 2018 meeting in Warsaw of the leaders of the Bucharest 9 of Baltic and East European countries. After the Zapad 2017 exercise the leaders call for a strong boost in NATO defences. Photo President of the Republic of Lithuania/R. Dackus

Russia’s strategic narrative

As has been suggested earlier, Russia’s strategy under Putin can be summarized in two goals: increasing its influence abroad and re-establishing its role as a global and regional power. Both seem to entail the strengthening of Russia at the expense of Western nations. In their article, scholars Payne and Foster state that Russia has ‘declared repeatedly that it views NATO as its enemy’.[20] This they use to explain Russia’s employment of military exercises like Zapad 2017. A main motive Russia mentions for exerting its military power is the alleged expansionist policy of NATO. As Putin himself declared at a conference in Munich in 2007: ‘… it is obvious that NATO expansion does not have any relation with the modernization of the Alliance itself or ensuring security in Europe. On the contrary, it represents a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust ....’[21] Indeed, the Western agenda as perceived by Putin’s presidency can only be described as the expansion of ‘Western influence in Russia’s traditional sphere of influence’.[22]

How can this narrative be explained? While NATO organizes regular military exercises in Europe, it has never done exercises on the scale of Zapad 2017.[23] Though it is important to note that in these instances, being part of Russia’s information campaign, the truth rarely matters. Vladimir Putin’s popularity amongst Russians is largely dependent on the perception that he is a strong leader, willing to protect so-called Russian values and interests against Western expansion.[24] Furthermore, Russia’s resistance to Western hegemony is often depicted as being ‘vital for survival of the Russian nation and state’. Thus, Putin cleverly uses this anti-Western narrative as a justification of his presidency, while also presenting Russia as an alternative for the Western model of modernity.[25] Moreover, portraying itself as an alternative power allows Russia to exclude itself from Europe institutionally and normatively.[26] In doing so Russia is no longer required to play by the international rules of the game and even justifies the way it tends to break these rules. This goes for Russia’s military actions as well, as Boulègue explains: ‘the notions of national sovereignty and intangibility of borders no longer have the same relevance for the Kremlin.’[27]

Battling disinformation

Meanwhile, the Zapad 2017 exercise showed the real problems of the European security strategy: the EU is unprepared for potential Russian aggression and unable to effectively deal with Moscow’s information campaign. Next to causing disarray and confusion about Zapad 2017, Russian propaganda has infected and still infects social media networks, influencing public opinion and meddling in elections and other forms of democratic decision-making. As put forward by European Commission’s security chief Julian King, a staggering ‘3,500 examples of pro-Kremlin disinformation contradicting publicly available facts, repeated in many languages and on many occasions’ have been identified.[28]

This is not to say that European countries are not trying to improve their capacity to respond to disinformation. As early as 2015, the European Council requested a plan of action to effectively address the Russian disinformation campaign. As a result, the East Stratcom Task Force was created,[29] whose main tasks include the explanation of EU policies in Eastern Partnership countries, the enforcement of media environment in the region and the analysis and correction of disinformation. In September 2017, the Task Force launched its own website EU vs. Disinformation, providing a database filled with cases of disinformation and even the so-called Disinformation Review, a weekly newsletter. [30] However, the actual effect of the European anti-disinformation campaign remains to be seen. As a study conducted during the 2016 American presidential campaign shows, attitudes are rarely affected by a fact-check. While corrective information does lead to the reduction of misconceptions, its effect on public opinion is minimal.[31] Still, this attempt to address the Russian disinformation campaign should be seen as a step in the right direction.

On Europe’s security strategies

Essentially, Zapad 2017 showed the evident lack of a (adequate) European strategic framework; a shared set of core assumptions about how security challenges should be dealt with. While it is clear that an exercise like Zapad 2017 does not immediately call for a military response, it can be viewed as part of a greater trend of deteriorating European security. The starting point of this deterioration is often placed in 2014, when Russia made several military incursions into Ukrainian territory. Ukraine was confronted with the invasion and subsequent annexation of the Crimean Peninsula by the Russian Federation, as well as with the declarations of independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions by Russia-backed separatist forces. The armed conflict in the Donbass area continues to this day. Admittedly Russia’s involvement in Ukraine was not the first act of Russian aggression in the neighbourhood, but it appears to mark a turning point in European threat-perception and security governance.

Next current security strategies - of both NATO and the European Union - and the response of the organisations to Russia’s revision of Europe’s rules-based order will be assessed. Mälksoo defines security strategies as strategies that ‘seek to repress ambiguity in an attempt to create some sort of order out of the surrounding uncertainty, or lurking chaos’.[32] It will become clear that the current security strategies fail to do this, because, while the EU and NATO strongly condemned Russia’s actions in Ukraine, they are generally indecisive about how to deal with Russia’s challenge to European security.

As an intergovernmental military alliance, one would expect NATO to be the first to guarantee European security if it is compromised. The alliance was created to protect Europe against Soviet aggression, but had been building towards more cooperation with Russia since the collapse of the USSR in 1991. For example, the 2010 NATO Strategic Concept of 2010 expressed the desire ‘… to see a true strategic partnership between NATO and Russia...’.[33] The Ukraine crisis changed all that; one could even say that NATO had been ‘reinvigorated’ by it. As is described by Derek Averre, the lesson NATO learned from 2014 is that ‘given the non-transparent build-up of Russia’s military capabilities near its western borders’ and a ‘sufficient level of interest and perceived opportunity’, Moscow is prepared to ‘trigger a rapid escalation from the non-military to a military phase in regional conflicts’.[34] As a response, NATO tried to reassure its members of the defence guarantees under Article 5 by the implementation of its Readiness Action Plan (RAP), which ‘ensures that the Alliance is ready to respond swiftly and firmly to new security challenges from the east and the south’.[35] Additionally, a NATO White Paper from 2015 refers to Russia as posing a ‘long-term threat to allies and EU member states’ and recommends a ‘more coherent strategy of engagement towards strategic neighbours in the East’, which would entail ‘the return to collective defence’.[36] In addition NATO has positioned equipment and forces in the Baltics, East-Central Europe and the Black Sea region.[37] Yet, it remains uncertain to what extent political response accompanies NATO’s military preparedness. Some blame NATO’s lack of substantive unity for its ineptness to challenge Russia.[38] In any case, as the Kremlin’s intentions remain unclear, NATO is reluctant to reintroduce direct confrontation and cause escalation of tensions.

Some suggest the European Union can only reach strategic autonomy, as called for in EUGS, through Europeanisation of NATO. Photo European Union/E. Ansotte

Since NATO does not give much clarity on a coherent security policy in Europe, maybe some answers can be found by looking at the European Union. As Maria Mälksoo explains, the EU’s security strategies are a perfect example of the EU’s growing aspiration ‘to provide physical security for its citizens’, while also feeling ‘a heightened sense of responsibility for serving as a ‘force for good’ in the world’.[39] Similarly, Alistair Shepherd notes the significance of EU’s blurring of internal and external security in understanding the Union’s role as an international security provider.[40] Isaac Kfir describes this early strategic culture as ‘encapsulating civilian power, with a focus on non-military […] means and the development of supranational structures’.[41] The EU’s first security strategy – the European Security Strategy (ESS) of 2003 – showed the EU’s aspirations to become a ‘global power’, but failed to ‘lay out clear policy objectives, means and instruments’.[42] The second strategy – the EU Global Strategy (EUGS) of 2016 – shows a more sobering perspective on European security. Brexit and the rise of nationalism in Europe made the focus of the security strategy shift to internal objectives, such as strengthening unity and keeping faith of citizens in European integration. Indeed, EUGS calls for more assertiveness, confidence, determination and resilience, while revealing increasing concerns about the EU’s ability to maintain peace and security in Europe.[43] Mai’a Cross notes the emphasis of the strategy on the importance of smart power, defined as the use of both coercion and co-option. On soft power, the strategy underscores the value of EU’s vast network of diplomats, and the importance of diplomacy. On hard power, it suggests that ‘the idea that Europe is exclusively a ‘civilian power’ does not do justice to an evolving reality’,[44] pointing out that the EU has many sources of hard power, including its economic sanctions imposed on Russia. Indeed, the change in the European security environment seems to have shaken the characterisation of European nations as so-called ‘civilian states’. Civilian states receive their legitimacy from their capacity to sustain economic growth and prosperity rather than their military capabilities, but recent years seem to show a renewed interest in military power. Likewise, it is important to note, when comparing EES and EUGS, the change in the regard towards Russia, from describing it as ‘a major factor in our society and prosperity’ to a country which ‘represents a key strategic challenge’ to European security.[45] One can only wonder why.

These two strategies provide the framework for the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), covered by articles 42 to 46 in the Treaty on European Union. Still, while the CSDP is designed to protect EU’s interests, contribute to international security and project power in order to prevent and resolve crises, it has not resulted in the creation of a European strategic doctrine and generated limited autonomous military capacity. Multiple past events show that CSDP has rarely been invoked as a useful political tool. As Derek Averre points out, the European Union has been involved in some capacity in all of the frozen conflicts in the former Soviet Republics but has not been able to reach a resolution in a single case,[46] or as Steven Blockmans lamented: ‘After the illegal annexation of Crimea and Russia’s indirect responsibility for the downing of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 in eastern Ukraine, what will it take before the EU can effectively confront a conflict on its borders and prove to both its own citizens and third countries that it has a meaningful role to play in foreign policy?’[47]

Possibly, this is tied to an additional problem found in dealing with Russia; the difference in threat perception amongst European countries. While Zapad 2017 corroborated the conclusions from Poland’s new defence review, according to the Secretary of State of Poland’s Ministry of Defence Bartosz Kownacki other countries regard the case differently. He claimed: ‘in other European countries, in the countries belonging to the so-called Old Europe, this threat is perhaps not perceived — they treat this threat in a different manner’.[48] Although it is understandable that the difference in location and economic dependency on Russia generates differences in threat perception, it proves to be a significant hurdle in maintaining European security.

Implications for European security

With Europe’s strategic strategies and their responses to Russia’s exclusion from European rules-based order outlined, the broader strategic implications arising from the deterioration of security in Europe’s neighbourhood will now be discussed. Then, multiple options on how Europe should develop its security strategy in order to effectively deal with Russian aggression will be presented.

As the assessment of European security strategy showed, the inaptness of the EU and NATO to effectively and unanimously respond to Russia resulted in a considerable amount of uncertainty about the future European security landscape. As Averre explains, ‘in the context of a resurgent Russia and increasing enlargement fatigue’, the European Union is unprepared to revise its security policy.[49] Opinions about implications for NATO are divided. Some experts argue that Russia’s increasing assertiveness helped NATO member states consolidate behind a new policy, while others point out the differing views on Russia among its members that hinder the constitution of an actual strategic approach. This creates what Averre calls a ‘vacuum of security governance’.[50] This vacuum is augmented by the uncertainty about Russia’s resilience. Economic hardship, caused by the Western sanctions and fluctuating oil prices, could very well influence Russia’s ability to sustain the costs of its foreign policy.[51] However, one should remember that in the light of Russia’s weak economy, it increasingly uses its military capabilities to assert its geopolitical influence. Zapad 2017 may serve as an example of this.

While it is clear that Europe should view Zapad 2017 as a confirmation of its perceptions of increased regional threats, experts disagree on how it should react to this. Focusing on NATO, scholars agree it is essential for NATO to learn to effectively counter Russian information campaigns and other forms of hybrid warfare.[52] As these tactics muddle usual foreign policy and make it unclear what would actually constitute an attack, it is important that NATO provides clarity on communication and action as to when Article 5 should be invoked. Additionally, Stevenson suggests that NATO should ensure the realisation of both its message of greater vigilance and its steps towards a greater military preparedness of collective defence.[53] Conversely, Averre finds fault with this emphasis on collective defence and deterrence, as it does little to ‘address the deterioration of the Russia-NATO relationship as well as the vacuum in security structure in the area’.[54] Instead, Russia and NATO should work on creating a constructive dialogue. Since the current security of Europe is covered in uncertainty, the possibility of potential misconceptions and misunderstandings that could lead to serious consequences should very well be reckoned with.[55] Maintaining open lines of communication could help demolish the ‘self-enforcing vicious circle of mutually biased perceptions of each other’, as well as opposing world views and conflicting narratives.[56] Moreover, emphasis should be placed on reassurance. NATO and the European Union should make an effort to address the Kremlin’s security concerns. A realistic view and understanding of Russia’s concerns about NATO’s deterrence plans and possible expansions could help undo Russia’s irrationality and unpredictability as perceived by European countries.[57]

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, Russian Foreign Minister meets with Federica Mogherini, High Representative for Foreign Affairs of the EU (September 25, 2018). Photo European Union/Tass

Scholars are equally divided on the role the European Union should play in dealing with Russia. Although the EU has tried to increase its importance as a European security provider, it remains unclear where its position fits between the more traditional security actors, such as the USA and NATO.[58] The wavering faith in the European integration project, as shown in Brexit and the rise of nationalism throughout Europe, further hinders this aspiration. Some suggest that the European Union can only reach ‘strategic autonomy’, as called for in EUGS, through ‘Europeanisation of NATO itself’.[59] As long as NATO exists parallel to the EU, as the argument goes, there is no real objective for the Union to reach security autonomy. By way of contrast, others argue that differentiation between the European Union and NATO could actually be helpful. Duke and Gebhard argue that greater differentiation between the EU and NATO could allow the former to bring down its integration dilemma with Russia. This would also make it more difficult for Putin to insist that the EU and NATO together are ‘part of a classical competition for international influence’.[60] Still, too much differentiation between the two organisations could help Russia exploit their differences, which should be avoided.

Conclusion

In the wake of growing Russian assertiveness, the military exercise Zapad 2017 can be seen as a clear part of a broader strategy to install and increase uncertainty about the European security environment. While the exercise displayed traditional military capabilities, its hybrid warfare aspect should not be overlooked. Russia’s strategy under Putin is directed at the re-establishment of Russia as a regional and global power, which seems to be achievable only at expense of Western influence in its ‘near abroad’. Next to displays of military means, like Zapad 2017, this strategy makes use of significant media and propaganda means as well. The current security strategies in Europe seem to be inapt to effectively deal with the Russian strategy, both in responding to potential aggression and in countering its disinformation offensive. In order to create a renewed confidence in its security, it is vital that European organisations like the EU and NATO maintain open lines of communication with Russia, which will decrease the chance of unintentional escalation of current tensions. In light of the changed tactics of warfare, including hybrid warfare, it is vital that NATO creates clarity on what exactly it perceives as an attack on one of its members. While opinions differ on the conflicting and collaborating roles of NATO and the EU, it is important that they define their security strategies more closely. As has become evident, the European security landscape has changed significantly over the last two decades, rendering views on the irrelevance of military force insufficient to explain current European societies. Russia’s self-exclusion from the European system of civilian states proves that the prevalence of military force still has its merits.

* This article is based on a paper Tjadina Herbert wrote during the course European Armed Forces and Societies at Leiden University under the supervision of prof. dr. Theo Brinkel. She is currently pursuing MA degrees in International Relations and Russian and Eurasian Studies at Leiden University.

Dit artikel is gebaseerd op een paper die de auteur schreef als student Russische Studies in het kader van het vak European Armed Forces and Societies dat prof. dr. Theo Brinkel geeft aan de Universiteit Leiden vanuit de KVMO-leerstoel Civil-Military Relations.

[1] Dave Johnson, ‘ZAPAD 2017 and Euro-Atlantic security’, in: Nato Review, 14 December 2017. See: https://www.nato.int/docu/review/2017/Also-in-2017/zapad-2017-and-euro-atlantic-security-military-exercise-strategic-russia/EN/index.htm.

[2] Igor Sutyagin, ‘Zapad-2017: Why Do the Numbers Matter?’, commentary for the Royal United Services Institute, 12 September 2017. See: https://rusi.org/commentary/zapad-2017-why-do-numbers-matter.

[3] The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Vienna Document 2011. See: https://www.osce.org/fsc/86597.

[4] Vladimir Mukhin, ‘Voinstvuyuschiye mirotvorcy’, in: Nezavisimaya Gazeta, 18 July 2008. See: http://www.ng.ru/regions/2008-07-18/1_peacemakers.html.

[5] Jonathan Stevenson, ‘The Wider Implicatons of Zapad 2017’, in: Strategic Comments 24 (2018) (1) iii.

[6] Mathieu Boulègue, ‘Five Things to Know About the Zapad-2017 Military Exercise’, in: Chatham House, 25 September 2017. See: https://www.chathamhouse.org/expert/comment/five-things-know-about-zapad-2017-military-exercise.

[7] ‘Zapad-2017 exercise puts Russian army’s ‘nervous system’ to test’, in: TASS, 19 September 2017. See: http://tass.com/defense/966366.

[8] Boulègue, ‘Five Things to Know About the Zapad-2017 Military Exercise’.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Maggie Tennis, ‘Russia showcases Military Capabilities’, in: Arms Control Today 47 (2017) (9). See: https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2017-11/news/russia-showcases-military-capabilities.

[11] Keith B. Payne & John S. Foster, ‘Russian Strategy: Expansion, crisis and conflict’, in: Comparative Strategy 36 (2017) (1) 80.

[12] Stevenson, ‘The Wider Implicatons of Zapad 2017’, iii.

[13] Andrius Sytas, ‘U.S. concerned about Baltic incidents in forthcoming Russian war games’, in: Reuters, 16 June 2017. See: https://www.reuters.com/article/nato-russia/u-s-concerned-about-baltic-incidents-in-forthcoming-russian-war-games-idUSL8N1JD3NF.

[14] Aaron Mehta, ‘In Russia’s Zapad drill, Poland sees confirmation of its defense strategy’, in: Defense News, 6 December 2017. See: https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2017/12/06/in-russias-zapad-drill-poland-sees-confirmation-of-its-defense-strategy/.

[15] Harry Cockburn, ‘Zapad 2017: Russia kicks off huge military exercises on Europe’s border’, in: The Independent, 15 September 2017. See: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/zapad-2017-russia-military-exercises-drills-europe-borders-kicks-off-war-games-putin-a7948456.html.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Andrey Suzdaltsev, ‘Ucheniya ‘Zapad 2017’. Isterika v NATO i bespokoystvo Lukashenko’, in: Ekho Moskvy, 27 August 2017. See: https://echo.msk.ru/blog/politoboz/2044798-echo/.

[18] Roman Azanov, ‘Kak ucheniya ‘Zapad 2017’ nadelali mnogo ‘shuma’ v Evrope i SShA’, in: Tass, 3 August 2017. See: http://tass.ru/armiya-i-opk/4459730.

[19] European External Action Service East Stratcom Task Force, ‘Zapad 2017: War Games in Russia, Belarus – and Vaisnoria?’, in: EU vs. Disinformation Campaign, 20 September 2017. See: https://euvsdisinfo.eu/zapad-2017-war-games-in-russia-belarus-and-vaisnoria/.

[20] Payne & Foster, ‘Russian Strategy: Expansion, crisis and conflict’, 80.

[21] Sharyl Cross, ‘NATO-Russia security challenges in the aftermath of Ukraine conflict: managing Black Sea security and beyond’, in: Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 15 (2015) (2) 154-155.

[22] Isaak Kfir, ‘NATO and Putin's Russia: Seeking to balance divergence and convergence’, in: Comparative Strategy 35 (2016) (5) 449.

[23] Tennis, ‘Russia showcases Military Capabilities’.

[24] S. Cross, ‘NATO-Russia security challenges in the aftermath of Ukraine conflict’, 159.

[25] Mikhail Suslov, ‘Russian World Concept: Post-Soviet Geopolitical Ideology and the Logic of ‘Spheres of Influence’’, in: Geopolitics (2018). Availlable at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14650045.2017.1407921.

[26] Derek Averre, ‘The Ukraine Conflict: Russia's Challenge to European Security Governance’, in: Europe-Asia Studies 68 (2016) (4) 715.

[27] Mathieu Boulègue, ‘The Russia-NATO Relationship Between a Rock and a Hard Place: How the Defensive Inferiority Syndrome Is Increasing the Potential for Error’, in: The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 30 (2017) (3) 371.

[28] Jon Stone, ‘Russian disinformation campaign has been ‘extremely successful’ in Europe, warns EU’, in: The Independent, 17 January 2018. See: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/russian-fake-news-disinformation-europe-putin-trump-eu-european-parliament-commission-a8164526.html.

[29] European Parliamentary Research Service, ‘Fake news’ and the EU’s response’, April 2017. See: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2017/599384/EPRS_ATA(2017)599384_EN.pdf.

[30] European External Action Service, ‘Questions and Answers about the East StratCom Task Force’, 8 November 2017. See: https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/2116/-questions-and-answers-about-the-east-stratcom-task-force_en.

[31] Brendan Nyhan, Ethan Porter, Jason Reifler and Thomas Wood, Taking Corrections Literally But Not Seriously? The Effects of Information on Factual Beliefs and Candidate Favorability, (SSRN, 29 June 2017). See: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2995128

[32] Maria Mälksoo, ‘From the ESS to the EU Global Strategy: external policy, internal purpose’, in: Contemporary Security Policy 37 (2016) (3) 376.

[33] Cross, ‘NATO-Russia security challenges in the aftermath of Ukraine conflict’, 156.

[34] Averre, ‘The Ukraine Conflict: Russia's Challenge to European Security Governance’, 710.

[35] NATO, ‘Readiness Action Plan’, 2016. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/ua/natohq/topics_119353.htm.

[36] Averre, ‘The Ukraine Conflict: Russia's Challenge to European Security Governance’, 710-711.

[37] Cross, ‘NATO-Russia security challenges in the aftermath of Ukraine conflict’, 161.

[38] Kfir, ‘NATO and Putin's Russia: Seeking to balance divergence and convergence’, 457.

[39] Mälksoo, ‘From the ESS to the EU Global Strategy’, 374.

[40] Alistair J.K. Shepherd, ‘The European Security Continuum and the EU as an International Security Provider’, in: Global Society 29 (2015) (2).

[41] Kfir, ‘NATO and Putin's Russia: Seeking to balance divergence and convergence’, 451.

[42] Mälksoo, ‘From the ESS to the EU Global Strategy’, 379.

[43] Ibid, 382.

[44] Ma’ia K. Davis Cross, ‘The EU Global Strategy and diplomacy’, in: Contemporary Security Policy 37 (2016) (3) 406.

[45] Mälksoo, ‘From the ESS to the EU Global Strategy’, 381.

[46] Averre, ‘The Ukraine Conflict: Russia's Challenge to European Security Governance’, 713.

[47] Steven Blockmans, ‘Ukraine, Russia and the need for more flexibility in EU foreign policy-making’, in: CEPS Policy Briefs No. 320 (Brussels, 25 July 2014). See: https://www.ceps.eu/publications/ukraine-russia-and-need-more-flexibility-eu-foreign-policy-making.

[48] Mehta, ‘In Russia’s Zapad drill, Poland sees confirmation of its defense strategy’.

[49] Averre, ‘The Ukraine Conflict: Russia's Challenge to European Security Governance’, 715.

[50] Ibid, 715-716.

[51] Ibid, 716.

[52] Boulègue, ‘The Russia-NATO Relationship Between a Rock and a Hard Place’, 376. Also: Cross, ‘NATO-Russia security challenges in the aftermath of Ukraine conflict’, 162. And: Stevenson, ‘The Wider Implicatons of Zapad 2017’, iii.

[53] Stevenson, ‘The Wider Implicatons of Zapad 2017’, iv.

[54] Averre, ‘The Ukraine Conflict: Russia's Challenge to European Security Governance’, 711.

[55] Cross, ‘NATO-Russia security challenges in the aftermath of Ukraine conflict’, 172.

[56] Boulègue, ‘The Russia-NATO Relationship Between a Rock and a Hard Place’, 376. Also: Cross, ‘NATO-Russia security challenges in the aftermath of Ukraine conflict’, 361.

[57] Ibid, 379-380.

[58] Mälksoo, ‘From the ESS to the EU Global Strategy’, 382.

[59] Jolyon Howorth, ‘EU-NATO cooperation: the key to Europe's security future’, in: European Security 26 (Taylor & Francis Online, 2017) (3).

[60] Simon Duke & Carmen Gebhard, ‘The EU and NATO's dilemmas with Russia and the prospects of deconflictation’, in: European Security 26 (2017) (3) 392.