In recent years Russia has conducted operations in several former Soviet states to establish a sphere of influence in those countries, prevent NATO and the EU from expanding and protect Russian interests and ethnic Russian minorities abroad. Moscow uses the Russian Federation Armed Forces (RFAF), which have developed a way of war that goes way beyond the use of military hardware alone. The Chief of the General Staff of the RFAF, General Valery Gerasimov, was the first to describe a framework for the new operational concept toachieve the objectives of Moscow’s near-abroad policy. The concept is based on lessons of the recent Estonia and Georgia conflicts and is characterized by a shift towards the use of non-military means and non-traditional domains, such as youth groups, cyber attacks, civil media and proxy forces. The concept has six subsequent phases and – from Moscow’s point of view – proved to be a successful approach to take over the Crimea region from Ukraine.

Lieutenant-Colonel A.J.C. Selhorst MMAS BEng*

[1]

[1]

In recent years, Russia has conducted operations in former Soviet states to prevent NATO and EU from expanding their sphere of influence into areas formerly part of the Soviet Union.[2] Western analyses of these conflicts have focused on the different forces Russia used to achieve its goals: cyber forces in Estonia, conventional forces in Georgia, and special operations forces (SOF) in the Crimea area of Ukraine. Western military experts were especially interested in the Russian Federation Armed Forces’ (RFAF) operational lessons, and the way they complemented their conventional military with SOF, airborne, and naval infantry as rapid reaction forces. Others also speculate how Russia would use cyber capabilities in future conflicts.[3] However, most of these studies have a limited scope with only a focus on military hardware. Moreover, most of them are based on Western assumptions about the Russian way of war, using military means within the traditional domains of air, sea, and land, expanded with the new cyber domain. In reality, the RFAF has changed its way of war into an operational concept to achieve the objectives of its near-abroad policy: establishing a sphere of influence in the former Soviet States, to protect Russian interests and ethnic Russian minorities abroad.[4] In 2003, Russia released a white paper in support of this new policy that described a change in military thinking and defined a new operational concept based on the integration of strategic, operational and tactical elements.[5] Vital to the new operational concept was the swift destruction, disruption, or control of communications, economics, infrastructure and political institutions to disrupt command and control of the enemy, with the use of proxy forces on land and in the cyber domain.

A Different View

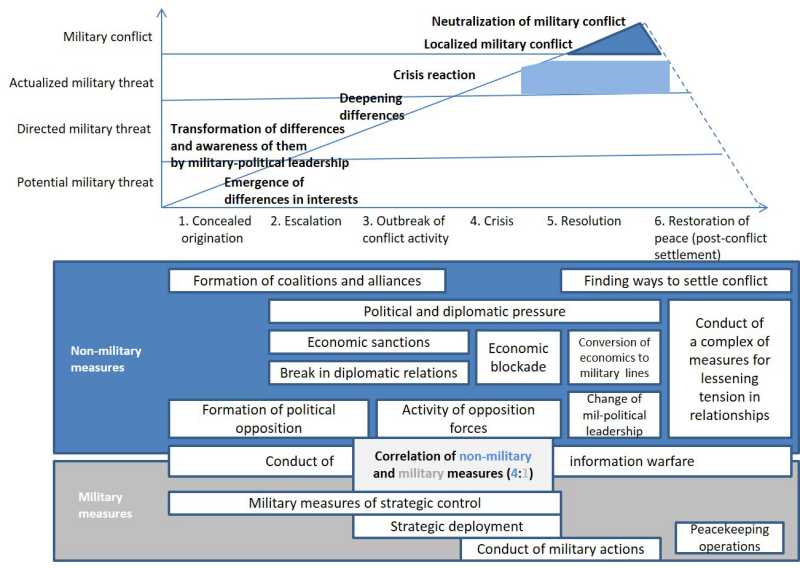

In February 2014, the Chief of the General Staff of the RFAF, General Valery Gerasimov, was the first to describe a framework for the new operational concept based on the lessons of the Estonia and Georgia conflicts (figure 1).[6] Gerasimov explains that the RFAF developed situational unique planning models to apply military and non-military means such as SOF, proxy forces, civil media and cyber capabilities to influence all actors, disturb communication and destabilize regions in order to achieve its objectives.[7] Although the article describes Gerasimov’s thoughts on means, phases and broad actions (ways) used in the new operational concept, it does not depict the effects and goals the RFAF wants to achieve with these actions nor does it depict how the RFAF uses social conditions in support of them.

During the Estonia, Georgia and Ukraine conflicts, Russia established civilian capabilities such as youth groups and state media and mobilized Russian ethnic minorities abroad by appealing to feelings of marginalization, a sense of self-worth and belonging, and a perception that Mother Russia has more to offer than the native country. Next, Russia masterly provoked international reactions and created an overall perception of despair of military and political leadership of the targeted countries, after which these countries were willing or forced to accept the new situation created by Russia. The so-called Gerasimov doctrine is a whole-of-society approach that causes a shift in means and domains and poses a challenge to the Western way of war due to the unfamiliarity with its ways, means, effects and goals.[8]

Figure 1 The Role of Non-Military Methods in the Resolution of Interstate Conflicts. Source: Valery Gerasimov, ‘The value of science in anticipation,’ VPK news, 27 February 2014. Accessed 2 July 2014, http://www.vpk-news.ru/articles/14632. Translated and created by Dr. G. Scott Gorman, School of Advanced Military Studies

The main purpose of this article is to reveal the tactical and operational level actions (ways) in the Gerasimov doctrine and the cumulative effects and goals that these actions need to achieve, in order to get a better understanding of the new Russian operational concept. This article first reviews the Gerasimov doctrine and its framework, followed by a short overview of the 2007 Estonia and 2008 Georgia conflicts, which the Russians used to refine their operational concept. This article concludes with the maturation of the Gerasimov doctrine in the 2014 Ukraine (Crimea) conflict and describes a detailed Russian operational framework that represents that doctrine.

Gerasimov’s Operational Framework in Theory

Russian Operational Art

Vasily Kopytko, professor at the Operational Art Department of the General Staff Academy, clarified in his article on Evolution in Operational Art that shifts in means and domains are not new for Russian operational concepts. Since 1920, the concepts evolved in five distinct periods, while foundations of the overarching Russian operational art largely remained the same.[9] In the first period, between 1920 and 1940, the operational concept encompassed front-scale and army-scale operations. The second period, which lasted until 1953, emphasized deep battle in combination with overwhelming firepower. Nuclear arms and missiles defined the third period, which ran from 1954 to 1985, while the fourth period, lasting until 2000, focused on the use of high-precision weapons. Kopytko defined the last shift towards non-military means and non-traditional domains in the operational concept as the fifth period of Russian operational art.[10] In the West, this concept is better known as the Gerasimov doctrine.

The Gerasimov doctrine did not evolve in a vacuum during the past decade, but is a twofold reaction to events that unfolded after the collapse of the Soviet Union. First, the evolution is a reaction of Russian leadership under President Vladimir Putin to counter the diminishing role of Russia in its traditional sphere of influence and the increasing role of the United States and NATO in that sphere. Second, it is also a reaction to the concerns of the Russian population and Russian Orthodox Church on the fate of 25 million ethnic Russians living outside Russia, their marginalization, and regional crises in the 1990s.[11] These crises provided Russia with lessons on how to use non-military means and social conditions for their operational concept, while at the same time the displaced Russians provided Russia’s leadership with a reason to re-establish its influence and a means to mobilize its society for conflict.

Reflexive Control or Perception Management

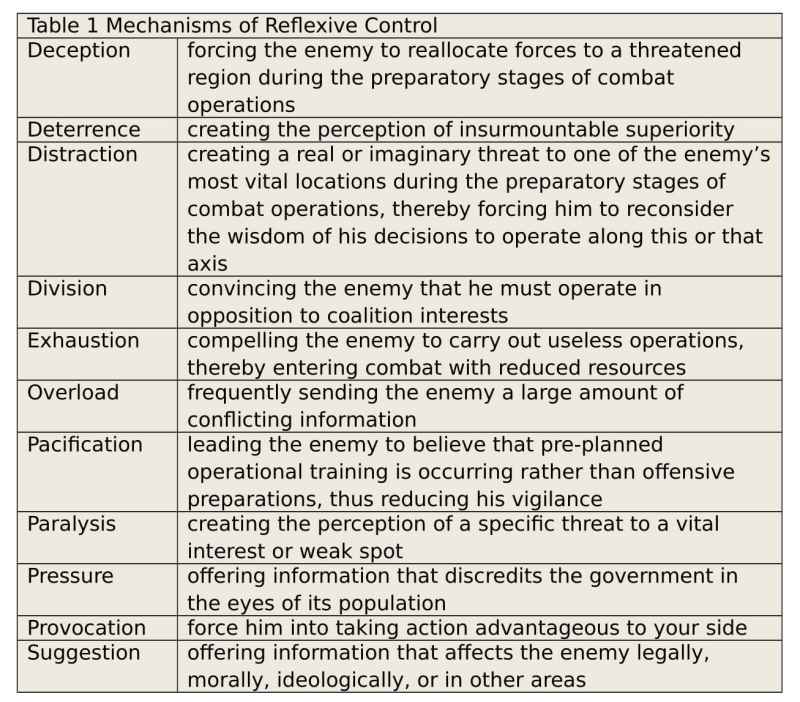

Gerasimov described the framework of the current Russian operational concept as the ‘[r]ole of Non-Military Methods in the Resolution of Interstate Conflicts.’[12] It incorporates six phases as shown in figure 1: concealed origin, escalation, outbreak of conflict activity, crisis and resolution, ending with the restoration of peace. This current Russian operational concept is a whole of systems, methods, and tasks to influence the perception and behavior of the enemy, population, and international community on all levels. It uses a systems approach based on ‘reflexive control’ (perception management) to target enemy leadership and alter their orientation in such a way that they make decisions favorable to Russia and take actions that lead to a sense of despair within their leadership and establish a base for negotiation on Russian terms. According to an expert, reflexive control ‘considers psychological characters of humans and involves intentional influence on their models of decision making.’[13] With these characteristics it reveals a cognitive model that reflects the internal structure of a decision-making system. This model delivers an approach of interrelated mechanisms based on history, social conditions and linguistics to deceive, tempt, intimidate or disinform. Reflexive control mechanisms can cause psychological effects ranging from deception to suggestion (see table 1). If one of these mechanisms fails, the overall reflexive control approach needs to engage another mechanism, or its original effects might degrade quickly.[14]

Table 1 Created by the author, based on Timothy L. Thomas, Recasting the Red Star: Russia Forges Tradition and Technology Through Toughness (Fort Leavenworth, Foreign Military Studies Office, 2011) 129-130

Finally, Russian operational art relies on concealment, also a technique of reflexive control, divided in two levels. Operational level concealment concerns ‘[t]hose measures to achieve operational surprise and is designed to disorient the enemy regarding the nature, concept, scale, and timing of impending combat operations.’ Strategic level concealment are ‘[t]he activities that surreptitiously prepare a strategic operation or campaign to disorient the enemy regarding the true intentions of actions.’[15]

Principles, Ways and Means

Gerasimov explained the new operational concept with some of the same principles as Georgii Isserson, a leading Soviet military thinker before World War II, did some 60 years ago. Isserson defined operational art as the ability of direction and organization in which operations are a chain of efforts throughout the entire depth of the operation’s area, with principles of shock, speed, efficiency, mobility, simultaneity, technological support, and a decisive moment at the final stage.[16] Gerasimov added to Isserson’s notion the application of asymmetric and indirect actions by military-civilian components, special operations forces and technical weapons to weaken the economy and destroy key infrastructure in a potential area of operations.[17] The new operational concept is therefore a mere continuation of the existing Russian operational art with different means, not only in the physical but also in the information domain.

Russia uses proxy forces, both paramilitary and cyber, supported by (media) institutions and companies, Spetsnaz and Cossack fighters to conduct different types of operations, like unconventional, information, psychological and cyber operations, as well as security forces assistance and strategic communication.[18] Russia manages these military and non-military means through state controlled companies and organizations under a centralized political command structure. This structure, together with the fact that the proxy forces consist of a mixture of Russians and ethnic Russians abroad, make that Russia not only exploits social conditions, but also cultural and linguistic factors in former Soviet states and at home to create proxy forces. It studies the behavior and demography of all potential opponents to reveal advantages it can exploit to achieve its objectives. Due to the migration policy in the Soviet-era, some 25 million Russians live in former Soviet states now surrounding Russia where they had better paid governmental jobs than in Russia itself, either as civil servants or teachers or in the military. Their new home countries marginalize their position through language legislation, rewriting national history, or limiting their civil rights, leading to mass-unemployment causing concerns in Russia among the Russian public and as a consequence the Russian government. The 2008 Russo-Georgian and 2014 Russo-Ukrainian conflicts show that areas with a high concentration of ethnic Russians are susceptible to Russian influence. In most cases, Russia will infuse the situation by granting citizenship to ethnic Russians or other inhabitants with grievances, creating Russian citizens in surrounding states. It is still one of Russia’s main strategic objectives to protect these ethnic Russians.

Gerasimov’s Operational Framework in Practice

Gerasimov tested his framework during the Estonia and Georgian conflicts, discovering the value of certain means in relation to the effects and goals they should generate. The next paragraphs describe the events that took place in these two conflicts, grouped in the phases of Gerasimov’s Operational Framework, linking effects to ways and means. The review starts with the concealed origin of all three conflicts, as they started some time ago.

Concealed Origin of the Conflicts

The concealed origin phase for Georgia, Ukraine, and Estonia started in 1991 as they all became independent states and separated from the Soviet Union. In Georgia tensions started immediately in 1991 over two breakaway regions: South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Both regions did not have large ethnic Russian populations, but the inhabitants had a distinctly different culture and language than the Georgian populace, more related to the areas north of them, inside Russia.[19] Tensions in Ukraine soon followed, largely because of an ethnic Russian minority in Crimea that wished to join Russia. At the same time, the Estonian government passed a law that rejected Russian as an official language, forcing the Estonian language on ethnic Russians as a requirement to earn Estonian nationality.[20] Russia saw these developments as a marginalization of the rights of ethnic Russians.[21] Over the following years, Moscow issued passports to the ethnic Russians in all three countries, creating a Russian minority, which it promised to protect.[22] Tensions increased as Estonia joined the EU and NATO in 2004 and subsequently refused Russia to build a pipeline to Germany in its littoral waters.[23] The rising tensions with Georgia and Ukraine were a result of Russia’s fear of NATO expansion and the desire for a regime change in both countries.[24]

Members of the Kremlin-loyal Nashi youth movement, that organized riots in Estonia in support of ethnic Russians, wave their organization’s flag during a rally in Moscow, December 2007. Photo Reuters

2007 Estonia crisis

The escalation phase in Estonia started with riots in the country and demonstrations at the Estonian embassy in Moscow as ethnic Russians living in Estonia saw the relocation of a Russian memorial (the Bronze Soldier) as a further marginalization of their rights.[25] A Russian youth group named Nashi [Ours], aided by Russian SOF, organized riots in the capitals of Russia and Estonia.[26] Assisted by Russian media, the rioters in Moscow and Tallinn protested for the human rights of ethnic Russians in Estonia, often comparing the ethnic Estonians with the Nazis of World War II.[27] Russia started issuing passports to ethnic Russians and pushed the Estonian government to make Russian the second national language and an official language of the EU.[28] Phase three of the Gerasimov-doctrine – outbreak of the conflict activity – started with cyber attacks that occurred in two waves. The cyber attack on 27 April 2007 was a spontaneous, uncoordinated attack on government, financial, economic, news and military networks.[29] Through media and Internet groups, Russian sympathizers encouraged Russians around the world to join the attacks and to download software to establish a worldwide network of supporting computers.[30] Nashi openly joined the cyber attacks, which faded away after a few days.[31] The second attack, which took place on 8 May 2007, was more sophisticated and overwhelmed Estonian governmental, economical, news and military networks.[32] The attack coincided with the anniversary of the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany, an event used by Russian sympathizers to stir up discontent. The second attack denied targeted institutions the use of their websites, disabled phone communication and disrupted the government’s email server, effectively hampering the government’s ability to lead the country and communicate with its allies.[33] The EU did not react due to an internal discussion on the crisis. As a result, Russia isolated the Estonian government for a few days from its inhabitants, its allies and its armed forces.

At this point, the conflict shifted very fast into the next phases of the Gerasimov doctrine: crisis and resolution. Russia tried to put the Estonian government under additional pressure by threatening to reduce gas delivery. It was unable to pressure Estonia into a settlement on the statue and language issues, despite the short period of isolation and the fact that Russia was the sole supplier of natural gas to Estonia. Later, Estonia decided to move the statue to a more prominent location then previously planned.[34] The impact of the attacks on Estonia and its economic, military and financial institutions was minimal and of short duration.[35] The crisis, however, verified Russian cyber warfare doctrine, comprising the targeting of populations, economic institutions, intelligence services and all layers of the civil service administration to temporarily disorient and cripple an entire government in an opposing state.[36] Russia also found a way to attack in a domain that had no legal counter actions; Estonia could not approach the United Nations nor its NATO allies, as these institutions at the time did not consider cyber attacks by individuals as state-on-state warfare.[37] As of this writing, the language issue remains unsolved.

2008 Georgia conflict

The Estionian cyber attacks were soon followed by the Russo-Georgian conflict. During the escalation phase early 2008 in Georgia, Russia covertly raised the number of peacekeeping troops by moving several hundred elite paratroopers disguised as peacekeepers into the region.[38] The next step in July 2008 was a large-scale Russian military exercise near the border of Georgia, enabling rehearsals for an invasion with conventional Russian troops.[39] Russia stepped up its information warfare campaign during the escalation phase and continued it during the outbreak of conflict and crisis phases.[40]

During these three phases of the conflict, the media targeted multiple audiences with several aims. First, they targeted Russians and breakaway region inhabitants, appealing to their patriotism, justifying the cause of an eventual intervention and convincing them to join cyber, proxy or partisan forces. The media campaign created a perception of Georgia supporting Nazi Germany to demonize the Georgian population and its government in the eyes of Russians.[41] Again the Nashi youth group supported this campaign.[42] Second, Russian mainstream media targeted the international community, projecting a ‘Kosovo’-like humanitarian intervention scenario on the situation in Georgia based on discrimination of and atrocities against ethnic Russians by Georgians to justify the intervention.[43] Third, the Russian media targeted the population of Georgia to discredit its government and set the stage for the abolition of the government. Besides the media engagement, the Russian information warfare targeted the Georgian government and military leadership, in the outbreak of conflict and crisis phases joined by cyber attacks, to isolate them.

The skirmish shifted to phase three of the Gerasimov doctrine – the outbreak of conflict phase – with cyber-attacks on NATO, Georgian government, the media and military networks.[44] The cyber attacks were unsophisticated disruptive attacks, not designed to penetrate the networks and misuse them, but to make them unusable.[45] Russian nationalists and Nashi joined the cyber attack, for which pro-Russia websites provided the software ready to download.[46] These cyber warriors infected many other computers that could participate in distributed denial of service attacks. At this point, the cyber attacks hampered the Georgian government’s ability to communicate with the world.

Prior and after military operations in South Ossetia, the use of the Russian language played an important part in the Russian campaign to stress cultural ties; workers reconstruct a school in Tskhinvali that was destroyed during the 2008 war. Photo AP, D. Lovetsky

The Russian information warfare campaign was a clear example of reflexive control to shape perceptions of public opinion prior to their military operations in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Russia used proven media techniques: (1) one-sidedness of information; (2) information blockade; (3) disinformation; (4) silence over events inconvenient for Russia; (5) ‘cherry picking’ of eyewitnesses and Georgians that criticized their government; (6) denial of collateral damage and (7) Russian versions of town names in the regions to suggest the motherland relation.[47] These techniques supported the reflexive control mechanisms of overload, pressure and suggestion. The Russian orchestrated cyber attacks established an extensive information blockade in the Georgian networks. The information warfare actions also attempted to provoke the Georgian government to take military action in the breakaway regions; and… it worked.[48]

The fourth phase of the Gerasimov doctrine – crisis – started on 7 August 2008 with a Georgian attack on South Ossetia, an action used by Russia to justify its intervention. With the help of the media, Russia created an image of a deliberate and unprovoked Georgian attack on both breakaway regions, forcing Russia to intervene in order to prevent a genocide.[49] The Russian coordinated cyber attacks hampered the Georgian government’s ability to govern its country, crippling army command and control systems, including air defense.[50] The RFAF invasion started during the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing (China) to prevent an international focus on the war and delay an international reaction. The speed of the Russian campaign leading to the temporary inability to react made it impossible for the Georgian government to counter Russian messaging. In order to justify the scale of the Russian invasion, Russian media and leadership exaggerated the Georgian military invasion.[51] Russia also used embedded journalists to deliver the evidence of Russian minority oppression and ethnic cleansing while preventing the Georgian government from countering these stories through the use of information warfare and cyber.[52]’

Russian peacekeepers, local proxy forces and Cossack units that answered the media call joined the regular RFAF fight.[53] Furthermore, the RFAF dropped forces in unmarked uniforms behind Georgian lines to conduct subversive actions.[54] Overwhelmed by force and simultaneous in-depth actions, together with the disruption of their situational awareness and communications, Georgian commanders were psychologically put on the defensive.[55] The Russian operational objective was to secure the breakaway regions. Once secured, the RFAF pushed on in support of other efforts, the navy blockaded the coast while the army seized transport infrastructure and threatened the pipelines to degrade the economy.[56]

Shifting towards the fifth phase – resolution – Russia stopped short of Tbilisi and international oil pipelines to avoid an international reaction. Isolated from the outside world and with a large part of Georgia occupied by Russia, the Georgian government became willing to negotiate peace terms. After ensuring their operational objectives, the RFAF withdrew on 12 August into South Ossetia and Abkhazia.[57] The results of the conflict caused NATO to reconsider offering an Alliance membership to Georgia, whereas Russia unilaterally recognized the independence of the separatist republics Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[58] Russia’s strategic objective was halting NATO’s expansion, warning other former Soviet states not to pursue NATO membership.[59] The conflict remains frozen up to this writing.

2014 Ukraine (Crimea) conflict

Detailed Operational Framework

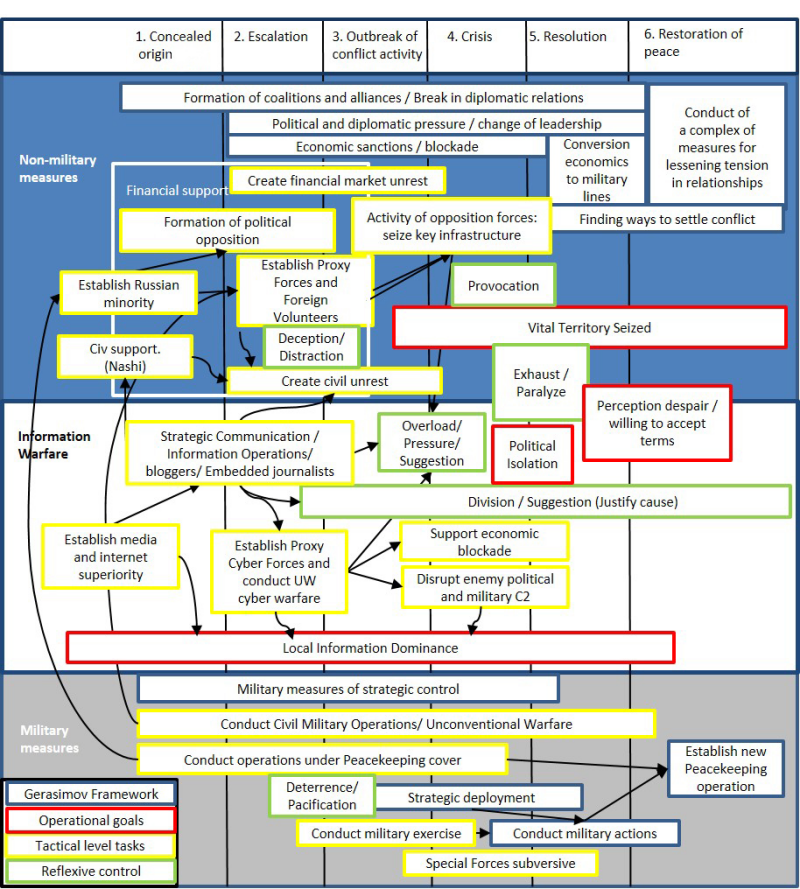

Analyzing the Estonian and Georgian conflicts, it is possible to define a more detailed operational framework.[60] Figure 2 depicts this detailed operational framework that includes Gerasimov’s six phases, three broad sets of measures (non-military, information related, and military), and broad tasks. Added to the original Gerasimov operational framework are detailed tasks, legal measures, effects, operational goals and their interdependences. Not depicted are the ever present operational and strategic level concealment. Russia never claims ownership until the sixth phase: restoration of peace. The next paragraphs describe the events that took place in the 2014 Russo-Ukraine (Crimea) conflict, related to the tasks, effects, and goals of the operational framework as Russia clearly used this framework, refined with lessons learned from the Estonian and Georgian conflicts.

Figure 2 Detailed Operational Framework. Created by the author, based on Valery Gerasimov, ‘The value of science in anticipation,’ VPK news, 27 February 2014. Accessed 2 July 2014, http://www.vpk-news.ru/articles/14632

The First Two Phases: Concealed Origin and Escalation

The Russo-Ukraine conflict has a long concealed origin. Anti-Russian and anti-Western feelings in Ukraine sparked uprisings during the last fifteen years: the 2003 Orange revolution, 2008 Crimea unrest, and 2013 Euromaidan revolution, being a prelude to the current Russo-Ukrainian conflict. Phase two, the escalation phase of the most current crisis, started after President Yanukovych of Ukraine fled the country in February 2014 and a pro-Western government assumed power.[61] Russia argued that this was an illegal act, as Ukrainians had not followed the impeachment procedure as depicted in Ukrainian law.[62] According to Russia, the new government acted against the security of Russians within Ukraine. Russia used the international humanitarian intervention discourse for its protection of Russians abroad to justify an intervention, again with reference to the Western arguments to validate NATO’s involvement in the Kosovo crisis.[63] The most likely reasoning for Russia’s commitment in Ukraine was to halt NATO expansion and remain in control of the harbor of Sevastopol, a Russian naval base at the Crimean peninsula, needed for all-year access to connecting seas and oceans.

Next step in the Russian operation was the media campaign to gain support in Crimea and Russia and to isolate the government of Ukraine, as depicted in the center of phase one and two: strategic communication. Television and the Internet were the dominant news media in Ukraine.[64] In Crimea, in total 95 percent of the population gathered their news from the television channels, which were almost all Russian state owned. Some 50 percent of the Crimean population gathered their news from the Internet, and 70 percent of the Crimean Internet users rely for their news gathering on the two major Russian social network sites available. Russians and Ukrainians analyzed information on sentiments gathered from the Internet, finding a 76 percent score for pro-Russian sentiments in the region. In Russia, these figures were comparable; more than 75 percent of the population trust their state-owned media. Independent news providers are rated with a 30 percent trustworthy score, and foreign news providers only score 5 percent reliability.[65] All in all, it is reasonable to state that Russia established information dominance in the first phase of the Gerasimov doctrine – concealed origin – and that it uses extra means during the following phase to retain this dominance depicted as the ‘local information dominance’ goal (red) in the center of figure 2.

Developments in the information domain contributed to this dominance. In 2010, Russia established social media groups such as the Kremlin School of Bloggers to support their reflexive control mechanisms.[66] Through a network of media and marketing departments of state-owned companies and Putin-friendly oligarchs, such as Gazprom Media, the Russian government acquired significant stakes in Russian and former Soviet states’ social media and influential websites. [67] In 2008 Roskomnadzor, an official Russian government body to supervise and censor all telecom, information technology and mass communication means and networks, was installed.[68] Roskomnadzor exercised control over popular websites. Their authority was based on a 2008 law that gave it legal means to shut down any mass media websites that could influence the public negatively and created control over messaging through the Internet comparable to TV and radio. The law stated that ‘[a]ny regularly updated Internet site can be included in the understanding of mass media, including personal diaries, various forums, and chats including.’[69]

The Russian information campaign started with the comparison of the Ukrainian government and their Western allies to Nazis, gays, Jews and other groups of people that Russia claimed were part of the conspiracy.[70] Russia showed swastikas on billboards and in the media to compare the government to Nazi Germany. This would remain the case throughout the conflict. In addition, since 2008, the Russian narrative is based on Russian Imperial history as told by popular nineteenth century writer Fyodor Dostoevsky. He claimed that ‘Russia’s special mission in the world was to create a pan-Slavic Christian empire with Russia at its helm.’[71] Putin quotes the writer often, together with hints towards a Dostoevskian Russia in his speeches. Russia also accused Western media to oversimplify demographical maps, signifying east and south Ukraine as predominant Russian ethnic. Meanwhile the diplomatic channels and Russian leadership started to emphasize the same issues of marginalized Russian minorities that seek reunification with Russia.

To prevent NATO and the EU from helping Ukraine, Russia intensified its information campaign. Russian media used past events to emphasize how aggressive NATO and the West were and how these powers violated agreements on NATO expansion restrictions into Eastern Europe.[72] Furthermore, to shape the EU’s perception of Ukraine as an unreliable partner, Russia made many public statements of Ukrainian violations of the Russian-Ukrainian agreement on revenue and energy rights related to the gas pipeline transiting Ukraine.[73] The messages further softened the already divided EU’s response, resulting in a temporary isolation of Ukraine. On 12 February leaders of pro-Russian organizations in Crimea gathered to discuss Crimea’s future and decided to support Russia.[74] The Russian Consulate in Crimea started issuing Russian passports to all inhabitants of the Crimea in the same week to create a Russian majority on the peninsula. Finally, on 14 February, a cyber-attack emerged, targeting one of Ukraine’s largest banks by malware, to support the unrest in the country and depicted as one of the non-military means at the top of figure 2.[75]

Third Phase: Outbreak of Conflict Activity

Almost two weeks later the third phase of the Gerasimov doctrine – outbreak of the conflict activity – started. Local paramilitary forces and Cossacks stormed the parliament and replaced it with pro-Russians, led by Sergei Aksyonov.[76] While pro-Russian sympathizers seized more key installations in Crimea, volunteers from Russia came to their aid and a 40,000 troops strong Russian Army started exercises at the Ukraine-Russian border.[77] In the days after the seizure, Cossacks remained to protect the parliament buildings against the Ukrainian army or pro-Ukraine sympathizers. Though Russia initially denied involvement, Russian-speaking militants in unmarked uniforms occupied military airfield installations as of 28 February.[78] The militants further occupied the regional media and telecommunication centers and shut down telephone and Internet communication in Crimea as more planes with new troops landed at the seized airfields.[79] It is this combination of unconventional warfare by special operations forces and proxy forces, together with an overwhelming conventional force conducting exercises at the border, that either lead to a desired provocation for a reaction or deterrence/pacification to prevent one, as depicted in figure 2.

For provocation or deterrence/pacification to work, the government needs to be more or less isolated, overloaded with disinformation as depicted in the center of figure 2. Therefore, the militants jammed radio and cell phone traffic to isolate Crimea further from Ukraine.[80] Russian coordinated cyber attacks started at the beginning of March and targeted the Ukrainian government, as well as NATO websites.[81] Cyber Berkut, a Ukrainian group that may possess ties to the Russian intelligence services, hosted the attacks. These attacks hampered NATO and Ukrainian leadership but they did not lead to isolation or overload. The United States called for a UN mission in the region in March; Russia declined.[82] Instead, Prime Minister Aksyonov of the autonomous Republic of Crimea, together with former Ukrainian President Yanukovych, called for a Russian intervention on 1 March and an independence referendum on 30 March.[83]

A poster calling people to take part in the March 2014 referendum in the Crimean city of Sevastopol. The poster reads: 'On 16 March, we are choosing' and 'or' (bottom), suggesting the region will face a grim future if it doesn't join the Russian Federation. Photo Reuters, B. Ratner

Fourth Phase: Crisis

On 7 March the fourth phase of the Gerasimov doctrine – crisis – started when paramilitary forces and Cossacks attacked Ukrainian military bases.[84] In some cases, Ukraine forces surrendered, while in others the paramilitary forces and Cossacks had to use more force, supported by the so-called ‘Little Green Men.’[85] These ‘Little Green Men’[86] were well armed, well trained, wore uniforms and masks and had no military emblems on their uniforms.[87] They would not talk to the media nor reveal their identity. While Russian officials commented on many events in the conflict they were consistently silent on sensitive issues, namely on the presence of Russian soldiers in Crimea.[88] With the government of Crimea removed, the reflexive control effects such as distraction, pressure, suggestion, and (local) isolation succeeded. Russia was never able to isolate the Ukrainian government though, as Western support for this government grew during the conflict.

Next in the Russian approach were the tasks that would lead to either provocation (a second time as a last resort) or exhaustion and paralysis of the Ukrainian government in Kiev. Although the Ukrainian government decided not to be provoked strategically, the result on the operational level was devastating. The combined actions led to the breakdown of morale of the Ukrainian forces in Crimea, through a combination of the reflexive control mechanisms of exhaustion and suggestion, as they surrendered their bases, in many cases to join Russian forces.[89] The ‘Little Green Men’ isolated Ukrainian forces in their bases and then used the local Internet and media to start Military Information Support Operations, media campaigns and intimidation in combination with bribery.[90] On 2 March the militants had already cut off the power lines at the Ukrainian Navy’s headquarters in Sevastopol, followed by the seizure of the Ukrainian Naval Forces communications facilities and the sabotage of all communication lines.[91] Remarkably, a covert cyber attack by Russian sympathizers did not take place. A reason for the absence might be that Crimea is a small area with only one Internet hub, which was already in the hands of the unknown troops: a hardware instead of a software disruption.

The final phases: Resolution and Restoration of Peace

The government in Kiev admitted that local police and armed forces in Crimea were corrupt, sympathizing with the uprising or had a low morale.[92] Next, Russian Agents of Influence[93] penetrated local intelligence and security forces. Together, the lack of communications and support to the bases led to the tactical and eventually operational isolation of the Ukrainian forces in Crimea and to their perception of despair. On the other side, the ‘Little Green Men’ remained disciplined. They did not reveal their identity and handled the skirmishes, not escalating them into a conventional war.[94] In April 2014, Russia admitted that the ‘Little Green Men’ were in fact RFAF Spetznaz and Airborne troops.[95] On 16 March, Crimea held the referendum for independence earlier than planned and 96.77 percent voted for a reunification with Russia (the turnout was 83.1 percent). The Russian Duma (parliament) signed a treaty on 18 March formally incorporating Crimea into Russia, starting the sixth phase, the restoration of peace. The conflict remains frozen up to this writing.

Conclusion and Recommondations

The current Russian operational concept uses military and non-military means that engage simultaneously and rapidly throughout all physical and information domains, through the application of asymmetric and indirect actions. Russia mitigates adversaries’ capabilities, creates chaos, seizes vital terrain and isolates enemy leadership. Although Russia uses a conventional force in its operational concept that is superior and with which victory is almost certain, it does not want to employ the forces as such for its near-abroad policy. Major combat is an undesired escalation as Russia seeks a psychological victory, not a physical one. Rather than military action, Russia wants to let the reflexive control system take its second and third order effects to annex areas. The culminating psychological effects of the reflexive control approach, like disorientation, suggestion and concealment need to overcome the provocation. At the end, it will cause exhaustion, paralysis and a perception of despair among the political and military leadership. These created perceptions and misperceptions set the leadership up for the final phase of the Gerasimov doctrine: resolution.

The evolution of the Gerasimov doctrine and its framework are not over as the Russian operational framework is all but a fixed set of means and ways. The Russian leadership may develop and employ new kinds of asymmetric means depending on the situation at hand. In General Gerasimov’s opinion, every conflict has its set of rules and therefore requires unique ways and means. On the other hand, the effects to achieve, related to phases and goals, are predictable as figure 2 shows. Therefore, the lesson for possible future conflicts is not to merely fixate on Russia’s physical means, but more importantly, to recognize the discussed phases and desired effects. Reassuring former Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact countries of NATO’s help in time of crisis and stationing NATO forces in Eastern Europe is therefore not enough. Building and maintaining resilient (inter)national political and military command and control within NATO to prevent the isolation and perception of despair of allies during a conflict, together with solving the problems concerning the ethnic-Russian inhabitants of Eastern European countries, may well be the best way ahead.

* Tony Selhorst is a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Royal Netherlands Army and is currently working at the Principle Policy Branch of the Ministry of Defense in the Hague. This article is based on his monograph Fear, Honor, Interest: An Analysis of Russia’s Operations in the Near Abroad (2007-2014) that he wrote for his Master’s degree course in Military Arts and Science at the School of Advanced Military Studies, US Army Command and General Staff College.

[1] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989) 157.

[2] Foreign Broadcast Information Service Central Eurasia, ‘Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation 2010,’ accessed 10 July 2014, http://news.kremlin.ru/ref_notes/461.

[3] Ariel Cohen and Robert E. Hamilton, The Russian Military and the Georgian War: Lessons and Implications (Monograph, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army, Carlisle, 2011); Roland Heickero, Emerging Cyber Threats and Russian Views on Information Warfare and Information Operations (Stockholm, Swedish Defence Research Agency, 2010).

[4] Nikolas K. Gvosdev and Christopher Marsh, Russian Foreign Policy Interests, Vectors, and Sectors (Thousand Oaks, CQ Press, 2014) 157.

[5] Ministry of Defense, The Priority Tasks of the Development of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (Moscow, The Defense Ministry of the Russian Federation, 2003) 59-6; Peter A. Mattsson and Niklas Eklund, 'Russian Operational Art in the Fifth Period: Nordic and Arctic Applications,' in: Revista de Ciencias Militares, Vol 1, No 1 (May 2013) 40; Marcel de Haas, 'Russia's Military Doctrine Development (2000-2010)' in: Russian Military Politics and Russia's 2010 Defense Doctrine, ed. Stephen J. Blank (Carlisle, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army, 2011) 14.

[6] Valery Gerasimov, ‘The value of science in anticipation,’ VPK news, 27 February 2014. Accessed 2 July 2014, http://www.vpk-news.ru/articles/14632.

[7] Michael R. Gordon, ‘Russia Displays a New Military Prowess in Ukraine’s East,’ in: The New York Times, 21 April 2014. Accessed 2 July 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/22/world/europe/new-prowess-for-russians.html?_r=0.

[8] Mattsson and Eklund, 40; Joint Publication (JP) 1.02, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Defense, 2013) 88.

[9] Vasily K. Kopytko, ‘Evolution of Operational Art,’ in: Voyennaya Mysl 17, no 1 (2008) 202-214.

[10] A.V. Smolovyi, ‘Problemniye voprosy sovremennogo operativnogo iskusstva i puti ikh rescheniya,’ in: Voyennaya Mysl no. 12 (2012) 21-24; Gerasimov.

[11] Nikolas K. Gvosdev and Christopher Marsh, Russian Foreign Policy Interests, Vectors, and Sectors (Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press, 2014), 164.

[12] Gerasimov.

[13] Volodymyr N. Shemayev, “Cognitive Approach to Modeling Reflexive Control in Socio- Economic Systems,” in: Information and Security 22 (2007), 35.

[14] Timothy L. Thomas, Recasting the Red Star: Russia Forges Tradition and Technology Through Toughness (Fort Leavenworth, Foreign Military Studies Office, 2011) 131.

[15] Thomas, Recasting the Red Star, 107-108.

[16] Georgii S. Isserson, ‘The Evolution of Operational Art,’ translation Bruce W. Menning (Fort Leavenworth, SAMS Theoretical Special Edition, 2005) 38-77.

[17] Gerasimov.

[18] Spetsnaz, or voiska spetsial’nogo naznacheniya, are ‘forces of special designation,’ often equated with U.S. Special Forces. Specific units such as Vympel conduct unconventional warfare. Cossack units are comprised of volunteers of ethnic Cossacks, a people with a historical bond to Russia that seek the restoration of the Russian Empire. They are organized in unions who coordinate their involvement.

[19] Advameg, Inc. ‘Georgia,’ Countries and their Cultures database. Accessed 7 September 2014, http://www.everyculture.com/Ge-It/Georgia.html#ixzz3CHXlfxMG.

[20] Claus Neukirch, Russia and the OSCE- The Influence of Interested Third and Disinterested Fourth Parties on the Conflicts in Estonia and Moldova (Flensburg, Germany: Centre for OSCE Research, 2001) 8.

[21] Ibid., 9-10.

[22] Janusz Bugajski, ‘Georgia: Epicenter of Strategic Confrontation,’ Centre for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), 12 August 2008; De Haas, 46; Cohen and Hamilton, 5.

[23] Vladimir Socor, ‘Nord Stream Project: Bilateral Russo-German, Not European,’ Eusasia Daily Monitor 4, no. 179 (2007). Accessed 1 September 2009, http://www.jamestown.org/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=33033&no_cache=1#.VAUMVsVdW_s.

[24] Marcel H. Van Herpen, Putin’s War: The Rise of Russia's New Imperialism (Lanham, Rowman and Littlefield, 2014) 233-234.

[25] Stephen Herzog, ‘Revisiting the Estonian Cyber Attacks: Digital Threats and Multinational Responses,’ in: Journal of Strategic Security 4, no. 2 (2011) 50-51.

[26] Max G. Manwaring, The Complexity of Modern Asymmetric Warfare (Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 2012) 91.

[27] Van Herpen, 130.

[28] Michael J. Williams, Tomorrow’s War Today,’ in: Central Europe Digest (May 2014) 9.

[29] Heickero, 39.

[30] Scott J. Shackelford, ‘Estonia Three Years Later: A Progress Report on Combating Cyber Attacks,’ in: Journal of Internet Law (February 2010) 22.

[31] Van Herpen, 130.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Heickero, 39.

[34] Bradley L. Boyd, Cyber Warfare: Armageddon in a Teacup? (Monograph, School of Advanced Military Studies, Fort Leavenworth, 2009) 35.

[35] Information Handling Services (IHS) Jane’s, Jane’s Sentinel Security Assessment – Russia And The CIS (Englewood, IHS Global Limited, 2014) 9.

[36] Heickero, 22.

[37] Cassandra M. Kirsch, ‘Science Fiction No More: Cyber Warfare and the United States,’ in: Denver Journal of International Law and Policy 40 (2012), 630-634.

[38] George T. Donovan, ‘Russian Operational Art in the Russo-Georgian War of 2008’ (Strategy Research, US Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, 2009) 9-10.

[39] Cohen and Hamilton, 19.

[40] Mattsson and Eklund, 34.

[41] Websites such as http://4international.me/2008/08/09/georgia-neo-nazi-war-against-ossetia-has-begun/ use the link between Nazi past and present situation.

[42] Manwaring, 92.

[43] Jadwiga Rogoza and Agata Dubas, ‘Russian Propaganda War: Media as a Long- and Short-range Weapon,’ in: Centre of Eastern Studies Commentary, no. 9 (11 September 2008) 2-3.

[44] US Cyber Consequences Unit (US-CCU), Overview by the US-CCU of the Cyber Campaign against Georgia in August of 2008 (Washington, D.C., US-CCU, 2009) 2-6.

[45] IHS Jane’s, 10.

[46] McAfee, Virtual Criminology Report 2009 (Santa Clara, McAfee, 2009) 6; Van Herpen, 130.

[47] Rogoza and Dubas, 3-4.

[48] Nathan D. Ginos, The Securitization of Russian Strategic Communication (Monograph, School of Advanced Military Studies, Fort Leavenworth, 2010) 11.

[49] Mattsson and Eklund, 35.

[50] US-CCU, 2-6.

[51] Donovan, 11-12.

[52] Mattsson and Eklund, 35; Hollis.

[53] Donovan, 14; ‘Cossack Volunteers to Help South Ossetia,’ in: Daily News Bulletin 8, English ed. (August 2008).

[54] Cohen and Hamilton, 42.

[55] Mattsson and Eklund, 34.

[56] Donovan, 8-16.

[57] Ibid., 7.

[58] Mattsson and Eklund, 34; Donovan, 1.

[59] Donovan, 6; Bugajski.

[60] A.J.C. Selhorst, Fear, Honor, Interest: An Analysis of Russia's Operations in the Near Abroad (2007-2014) (Monograph, School of Advanced Military Studies, Fort Leavenworth, 2014) 37-45.

[61] Steven Woehrel, Ukraine: Current Issues and U.S. Policy (Washington, D.C., Congressional Research Service, 2014) 1; Janis Berzins, Russia’s New Generation Warfare in Ukraine: Implications for Latvian Defense Policy ( Riga, National Defense Academy of Latvia, Center for Security and Strategic Research, 2014) 2-3.

[62] Berzins, 2-3.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Gallup, Contemporary Media Use in Ukraine (Washington, D.C., Broadcasting Board of Governors, 2014) 1-2.

[65] Julie Ray and Neli Esipova, ‘Russians Rely on State Media for News of Ukraine, Crimea. Few trust Western media or independent Russian media,’ Gallup World, July 2014. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://www.gallup.com/poll/174086/russians-rely-state-media-news-ukraine-crimea.aspx.

[66] Van Herpen, 130.

[67] Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), ‘Kremlin Allies’ Expanding Control of Runet Provokes Only Limited Opposition,’ in: Media Aid (28 February 2010) 1-5.

[68] Official website of the Russian Government, ‘Current Structure of the Government of Russia’ (in English). Accessed 24 march 2015, http://www.government.ru/content/executivepowerservices/currentstructure/.

[69] CIA, 1-5.

[70] Alan Yuhas, ‘Russian Propaganda over Crimea and the Ukraine: How Does it Work?’ in: The Guardian, 17 March 2014. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/17/crimea-crisis-russia-propaganda-media.

[71] Andrew Kaufman, ‘How Dostoevsky and Tolstoy Explain Putin’s Politics,’ Andrew D. Kaufman, 7 April 2014. Accessed 24/11/2014, http://andrewdkaufman.com/2014/04/

dostoevsky-tolstoy-explain-putins-politics/.

[72] Dmitry Babich, ‘Media wars around Crimea: Russia not impressed by liars’ empty threats,’ The Voice of Russia, 20 March 2014. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://voiceofrussia.com/2014_03_20/Russia-not-impressed-by-liars-empty-threats-1813/.

[73] Ginos, 11.

[74] Robert Coalson, ‘Pro-Russian Separatism Rises In Crimea As Ukraine's Crisis Unfolds,’ Radio Free Europe, 18 February 2014. Accessed 24/11/2014, http://www.rferl.org/content/ukraine-crimea-rising-separatism/25268303.html.

[75] IHS Jane’s, 8.

[76] ‘Wie is de Baas op de Krim (Who is the Boss of the Crimea),’ NOS, 11 March 2014. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://nos.nl/artikel/622011-wie-is-de-baas-op-de-krim.html.

[77] Steven Woehrel, Ukraine: Current Issues and U.S. Policy (Washington, D.C., Congressional Research Service, 2014) 1.

[78] ‘Militaire Spanning Krim Stijgt (Military Tension Crimea Rises),’ NOS, 28 February 2014. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://nos.nl/artikel/617230-militaire-spanning-krim-stijgt.html.

[79] ‘Kiev: Invasie door Russisch Leger (Kiev: Invasion by Russian Army),’ NOS, 28 February 2014,. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://nos.nl/artikel/617425-kiev-invasie-door-russische-leger.html.; IHS Jane’s, 8.

[80] IHS Jane’s, 8.

[81] Adrian Croft and Peter Apps, ‘NATO websites hit in cyber-attack linked to Crimea tension,’ 16 March 2014. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-nato-idUSBREA2E0T320140316 Accessed 4 October 2014;

Russel Brandom, ‘Cyberattacks Spiked as Russia Annexed Crimea,’ The Verge, 29 May 2014. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://www.theverge.com/2014/5/29/5759138/malware-activity-spiked-as-russia-annexed-crimea.

[82] ‘Internationale Missie Oekraine (International Mission Ukraine),’ 1 March 2014. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://nos.nl/artikel/617484-internationale-missie-oekraine.html.

[83] ‘Referendum autonomie Krim eerder (Crimean Autonomy Referendum Earlier),’ NOS LINK

[84] ‘Russen Vallen Basis Krim Aan (Russians Attack Crimea Basis),’ NOS, 7 March 2014. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://nos.nl/artikel/620412-russen-vallen-basis-krim-aan.html.

[85] The Western media addressed them as ‘Little Green Men’, but later Russian Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu and President Putin called them the ‘Polite People.’

[86] See also: ‘De Groene Mannetjes’, editorial in: Militaire Spectator 184 (2015) (5) 210-211. Accessed 27 November 2015, http://www.militairespectator.nl/thema/editoriaal/de-groene-mannetjes.

[87] ‘Pro-Rusland-Campagne op Dreef (Pro-Russia-Campaign on a Roll),’ NOS, 13 March 2014. Accessed 4 October 2014, http://nos.nl/artikel/622506-proruslandcampagne-op-dreef.html.

[88] Yuhas.

[89] Berzins, 4-5.

[90] Ibid.

[91] IHS Jane’s, 8.

[92] Woehrel, 3.

[93] The Russian Agents of Influence probably belong to the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, the SVR (Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki)

[94] Berzins, 4-5.

[95] Woehrel, 2; Berzins, 4.