During the 1980s Tom Clancy gained fame writing techno-thrillers, situated in a fictional world, using contemporary Cold War-themes. His novels, amongst others, contributed to reviving attention to the concept of Maskirovka (Russian military deception). Especially in Red Storm Rising, the concept was extensively used within a political/strategic context. More than twenty years later, Maskirovka and other Soviet/Russian concepts are once again relevant - as the Russian Federation is applying them in various theatres - bordering NATO territory. This article will focus on a more refined version of Maskirovska, called Reflexive Control Theory (RCT). The aim of this article is to provide an insight into the concept of RCT, its application in the past, present and future and how it affects NATO and the Netherlands Armed Forces.

Major C. Kamphuis BSc.*

‘And the Maskirovka?’

‘In two parts. The first is purely political, to work against the United States. The second part,

immediately before the war begins, is from KGB. You know it, from KGB Group Nord. We

reviewed it two years ago.’

Tom Clancy, Red Storm Rising (1986) p. 18

First of all, the article explores the concept of Maskirovka as a broader foundation for the application of Reflexive Control (RC). Secondly, the concept of RC will be discussed and put into a historical context. This will be followed by a review of recent and ongoing applications of RC in eastern Ukraine and the Crimea. The article concludes with a description of how RC could be - and is already - being applied in the Baltics, with a focus on the implications for (Dutch) NATO ‘enhanced Forward Presence’ (eFP) units operating in the Baltics.

Lithuanian President Grybauskaite, Prime Minister Rutte and former Commander in Chief Middendorp visit Dutch troops deployed in NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence, 2017. Photo Office of the President of the Republic of Lithuania, R. Dackus

All original literature on RCT is written in Russian, a language which the author does not master. Therefore, the literature study has been conducted using Dutch and English publications. Timothy Thomas, an American analyst at the Foreign Military Studies Office, has published several extensive studies over the past decades. He based them on the original works of Vladimir Lefebvre and other Russian pioneers of RCT. Therefore, the works of Thomas have been used in this study as a replacement for the original Russian publications.

The concept of Maskirovka explained

Maskirovka is a Russian concept predating the Soviet Union, with the first official Maskirovka school being established in 1904.[1] Maskirovka is a concept encompassing multiple elements, such as camouflage, concealment, deception, misinformation, imitation, secrecy, security, feints, and diversion. The noun Maskirovka used to be translated as ‘to mask’. First of all, this does not cover the concept at all, and furthermore it is actually impossible to translate a noun as a verb.[2]

In the past, but also as we speak, this prevented actors from appreciating the full extent of the concept and falsely mistake it for camouflage and concealment. In 2014, while writing about the conflict erupting in the Ukraine, journalist Oestron Moeler defined Maskirovka as deliberately misleading the opponent with regard to one’s own intentions, causing the opponent to make wrong decisions and thereby playing into one’s own hand.[3] This definition of Maskirovka is astoundingly similar to modern-day definitions of RC. This is not a coincidence: the concepts of Maskirovka and RC have a lot in common. Moreover, RC can be regarded as a refinement of Maskirovka.[4] Deception is a core element of both Maskirovka and RC. In order to effectively deceive an opponent, it is adamant that whatever is undertaken must appear highly plausible to the enemy, and it needs to conform to both his perspective of Russian doctrine and to his own strategic assumptions.[5]

Reflexive Control

Origins of RC

RC is a concept that was pioneered in the Soviet Union in the 1960s by Vladimir Lefebvre, a psychologist and mathematician, who is considered the founding father of this concept. RC is a special kind of influence activity, and it predates the modern concept of information warfare. It was not until the late 1970s that this concept was formally adopted by the Soviet military, although Soviet military thinkers were already interested in the concept almost a decade before. During the time that RC was not mentioned in any Soviet military handbook. It did not officially exist and thus could not be mentioned in any military publication. Officers publishing in relevant Soviet military journals, such as Voennaya mysl (Military Thought), wrote about ‘control of the enemy’ to circumvent this issue.

Definitions of RC

RC is defined by Lefebvre as ‘a process by which one enemy transmits the reasons or bases for making decisions to another’, or as he put it in the title of one his books, ‘a Soviet concept of influencing an adversary’s decision-making process’.[6] Timothy Thomas defines it as ‘a means of conveying to a partner or an opponent specially prepared information to incline him to voluntarily make predetermined decision desired by the initiator of the action’.[7] The core concept in these definitions is that an actor provides specific and predetermined information to another actor, with the explicit goal to control the decisions made by the receiver. In other words, controlling the decision-making process leading to the receiving actor making decisions that will lead to his defeat and/or enable the desired outcome for the transmitting actor.

Keir Giles, researcher at the NATO Defence College, mentioned that in Russian sources the phrase ‘Reflexive Control’ is no longer a current phrase. It has been partially replaced by the phrase ‘Perception Management’. The latter phrase appears to have been adopted directly from western literature on Information Operations.[8] This notion contradicts statements made by Thomas in two different studies from 2004 and 2017. Thomas explicitly states that RC differs from any known western concept, because it is about controlling perception, and not about managing perception. Managing perception, and not controlling perception is the essence of western perception management within the context of information warfare.[9] Because the Soviet/Russian concept of RC predates western thinking on information operations, it is likely that Thomas’s conclusion is right. Therefore, in this article RC is considered as a different concept than perception management.

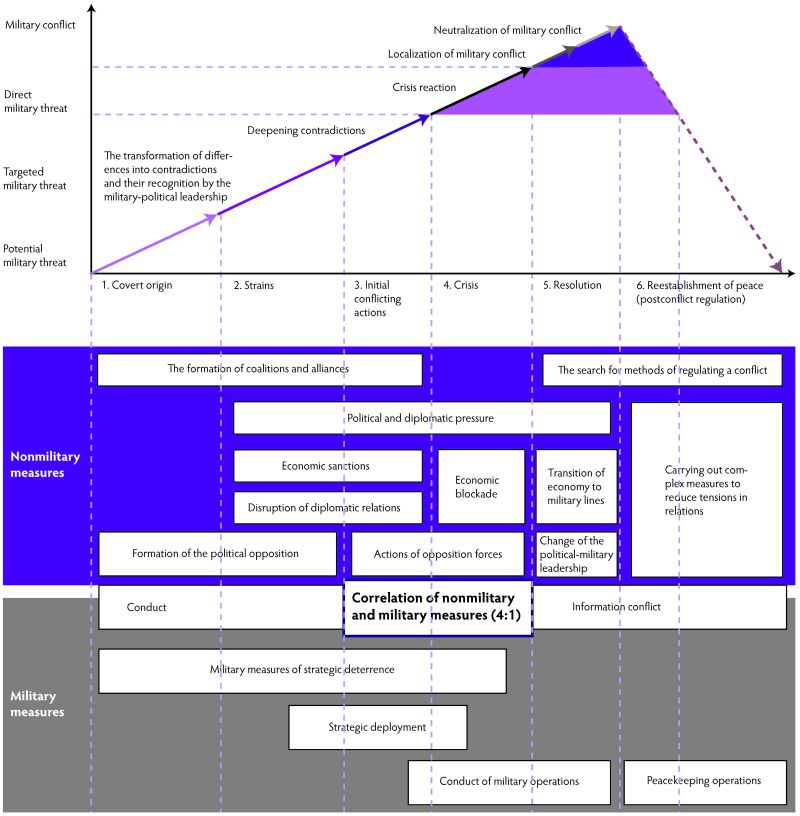

Figure 1 Graph of the Gerasimov doctrine (Source: Charles K. Bartles, ‘Getting Gerasimov Right’, in: Military Review, January-February 2016, p. 35. Reprinted with permission)

RCT in modern day Russian doctrine

Russian commanders in warfare have to apply RC, because one of the prime goals is to interfere with the decision-making process of an enemy commander. Therefore, Russia considers RC at least as important as conventional firepower or even as a more decisive factor.[10] It is an essential part of the modern Russian operational art, as described in the so-called Gerasimov Doctrine. This framework was published in February 2014 by General Valery Gerasimov, Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Federation Armed Forces (RFAF). This doctrine can be used as a planning tool for the RFAF to apply military and non-military means to influence all actors in order to achieve its goals. The doctrine describes six distinct phases in which a conflict develops from a concealed origin up to restoration of peace.[11]

According to General Valery Gerasimov, Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Federation Armed Forces (RFAF), RC is at least as important as conventional firepower. Photo U.S. Department of Defense, M. Cullen

Gerasimov himself claimed that his doctrine is not a description of Russian doctrine at all. Instead it is a description of what the West (and especially the USA) has done in the last decades in various conflict areas, such as Iraq and Afghanistan. This claim is in fact supported by various thinkers within the western strategic community. They claim that recent Russian publications on modern warfare are merely an attempt to catch up conceptually with the reality of modern warfare, with which the West has already been grappling for almost two decades.[12] Taking this into account, it may well be that Gerasimov actually did describe what he had observed in Iraq and Afghanistan, but with the purpose to adopt this within the framework of modern-day Russian military thinking.

Hybrid Warfare

The western world, especially NATO, categorizes current Russian military activity as Hybrid Warfare. In Russian literature Hybrid Warfare is no longer a valid term. Instead, ‘non-linear warfare’ is used, and more recently ‘New Type Warfare’, to describe present-day military activity.[13] I will continue to use the term Hybrid Warfare, because this is in line with all relevant contemporary western publications. Frank Hoffman defined Hybrid Warfare as a fusion of war forms that blur regular and irregular warfare. Gerasimov states the following in this regard: ‘The focus of applied methods of conflict has altered in the direction of the broad use of political, economic, informational, humanitarian, and other non-military measures (…) applied in coordination with the protest potential of the population. All this is supplemented by military means of concealed character, including carrying out actions of informational conflict and the actions of special operations forces.’

According to recent NATO studies, this renewed military thinking is based upon Soviet legacy theories, such as Soviet Deep Operation Theory (DOT) and RC. In Soviet times, DOT originally focused on launching Special Forces, and specifically designed Operational Maneuver Groups, literally deep into the enemy rear. Nowadays, the physical component has been (largely) replaced by achieving effects in the enemy rear using more subtle techniques, such as RC.[14]

Mechanisms behind the concept of RC

The ‘reflex’ within RC involves the specific process of imitating the enemy’s reasoning and cause him to make a decision unfavourable to himself. So, the reflex is not the reaction of the opponent an actor seeks to create, but it is the ability of an actor to imitate the opponent’s thoughts or predict his behaviour. A receiver will make a decision based on the idea of the situation which he has formed. This idea is formed by a set of concepts, knowledge, insights, ideas and experience of the receiver. This set is called the ‘filter’ within RC. The filter assists in separating necessary from useless information. The chief task of RC is, therefore, to find the weak link in the filter and exploit it. By exploiting this weak link an actor can create model behaviour in the system of the opponent he seeks to control.[15]

The aforementioned filter does not only include humans. In the modern age, automated data-processing systems composed of a significant part of decision-making processes, are part of the filter. Therefore, RC also includes digital information and is applied in the cyber domain. Methods to achieve RC are varied and include camouflage, disinformation, encouragement, blackmail by force and compromising officials and officers. It is considered to be more of a military art than a military science.[16]

How to apply RCT

In order to achieve a higher degree of reflex than the opponent, it is insufficient just to understand the opponent and his filter. One must also be capable of achieving surprise and act far more differently from what the opponent expects. Surprise and unforeseen behaviour can be achieved by means of stealth, disinformation and, most important, avoidance of stereotypes.[17] This appears to be paradoxical, because part of RC is to reinforce the stereotypes an opponent has of his enemy and to convince him that that enemy will do what he thinks is the most logical option for him. But, eventually all it takes is to surprise the opponent by doing something which is indeed unpredictable and defies the (reinforced) stereotypes.

It would be a grave misunderstanding to think that Russian commanders are predictable, just because the Russian army is known to operate by using sets of predetermined tactics and procedures. The broad palette of available tactics and procedures offers a commander enough options to devise operations which are intricate enough to deceive his opponent. The recent improvements in C3I within the armed forces also offer better means to orchestrate the execution of these intricate plans.[18]

Major General (retired) Ivonov published a checklist for commanders that gives a practical insight into how Russian commanders can apply RC:

- Power pressure: using a superior force, threats of sanctions, raising the alert status of troops, combat reconnaissance, weapon tests, supporting subservice elements destabilizing the enemies rear, playing up victories and show mercy to an enemy ally that has stopped fighting.

- Measures to present false information about the situation: concealment (display weakness in a strong place), creation of mock installations, concealing true relations between units (or create mock ones), maintain secrecy about new weapons, weapons bluffing, deliberately losing critical documents (some real, some fake), subversion, leaving open a route to escape encirclement and forcing the enemy to take retaliatory actions involving expenditure of forces, assets and time.

- Influencing the enemy’s decision-making algorithm: systematic conduct exercises/demonstrations in accordance with what the enemy already perceives as being routine modus operandi, publishing a deliberate distorted doctrine, striking enemy C2 and key figures and transmitting false background data.

- Altering the decision-making time: unexpectedly start combat operations, transmitting information about the background of an analogous conflict to reinforce the enemy’s assumptions and let him make hasty decisions that alter the mode of his operation.[19]

Basic elements of RC

Colonel S.A. Komov, an influential writer about RC in the 1990s, made the following list of basic elements of RC:

- Distraction: create a real or imaginary threat to the enemy’s flank or rear during the preparatory stages of combat operations, forcing him to adapt his plans.

- Overload (of information): frequently sent large amounts of conflicting information.

- Paralysis: create the perception of an unexpected threat to a vital interest or weak spot.

- Exhaustion: compel the enemy to undertake useless operations, forcing him to enter combat with reduced resources.

- Deception: force the enemy to relocate assets in reaction to an imaginary threat during the preparatory stages of combat.

- Division: convince actors to operate in opposition to coalition interests.

- Pacification: convince the enemy that pre-planned operational training is occurring rather that preparations for combat operations.

- Deterrence: create the perception of superiority.

- Provocation: force the enemy to take action advantageous to one’s own side.

- Suggestion: offer information that affects the enemy legally, morally, ideologically, or in other areas.

- Pressure: offer information that discredits the enemy’s commanders and/or government in the eyes of the population.[20]

The literature does not provide a conclusive answer, whether the elements described in the two lists above have to be addressed as a complete package or whether a commander can pick specific elements in order to be effective in achieving his goal. Many elements, however, appear to be interlinked. Some elements even appear to be the outcome of the implementation of other elements. As an example, applying overload and paralysis can contribute to achieving exhaustion, just as deception can. It can therefore be concluded that in order to be successful, all elements have to addressed, but to different degrees. It depends on the precise situation how important a specific element is to achieve success. Furthermore, the different elements offer a commander the option to change the focus of his operation. If a certain element is not effective (or even counterproductivity) it is possible to increase the focus on another element to improve the chances of being successful eventually.

RC in relation to the maneuvrist approach

In Dutch military doctrine, fighting power is composed of a physical, mental and conceptual component. The aim of the maneuvrist approach is to defeat an opponent by breaking his moral and physical cohesion, instead of destroying him step by step (attrition). The maneuvrist approach emphasizes the need to understand and attack the conceptual and mental component of an opponent, besides attacking the physical component.[21]

While looking at the concept of RC, it can be argued that this concept is in fact a Russian incarnation of the maneuvrist approach, with a great emphasis on attacking the conceptual component of an adversary. In order to be effective in applying RC one must understand the opponent, which enables one to provide him with information which not only reinforces his assumptions, but also his natural way of reasoning. This inclines him to make decisions that will contribute to his own defeat. Combined with practical guidelines as formulated in the previous paragraph, RC offers an excellent manual to apply the maneuvrist approach in a pure form: out-maneuver the opponent mentally and conceptually (preferably) before or without engaging him physically. This might be a coincidence, but it is likely an indicator of the integration of (successful) western doctrine in a pre-existing Russian concept.

Past application of RC: two historical examples

In the past the Russian military and security forces actively applied the concepts of RC. The first example is from the Cold War, when the Soviet Union tried to alter the US perception of the nuclear balance. The goal was to convince the West that Soviet missile capabilities were far more formidable than they actually were. To achieve this, they, amongst others, exhibited fake ICBMs at military parades in order to create the illusion that a single missile could carry huge multiple warheads.[22]

Forward to the victory of communism’: in the Cold War the Soviet Union tried to mislead the West also during military parades. Photo Nationaal Archief/Collectie Spaarnestad/UPI

At the same time Soviet authorities made sure that military attachés and known western intelligence officers would observe the parades closely. They further created a trail of collateral proof that western intelligence services would discover when investigating the fake ICBMs, which would lead them even further astray.[23] The ultimate goal was to lead foreign scientists, who would try to copy the advanced technology, down a dead-end street. By doing so, the West would be wasting precious time, money and scientific research capacity.[24]

The second example occurred during the occupation of the Russian White House in October 1993 conducted by Members of Parliament and their supporters, advocating a return to communism. On the day of a massive demonstration by supporters of the occupation, the police permitted one of its communication posts to be overrun by protesters, giving them access to secured communication channels. At the same time, the military authorities broadcasted deceptive messages, which could be received by the protesters. The messages contained a fake conversation of two high-ranking officials of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), discussing the imminent storming of the White House. They specifically mentioned aiming for ‘the Chechen’. One of the key persons orchestrating the occupation was Ruslan Khasbulatov, the Speaker of Parliament who was of Chechen ethnicity. Within minutes of broadcasting the fake messages, Khasbulatov and other key figures appeared on the balcony of the White House and asked the crowd of supporters outside to go to the Ostankino TV station and capture it. This public call for disobedience was exactly what the security forces had aimed for. Now they could legally act against the key figures and end the occupation.[25]

Modern day application of RC

The Crimea

On March 18, 2014, Russia annexed Crimea catching almost everybody off guard including the Ukrainian government and security apparatus, but also many decision-makers within NATO. The Russian Military disguised its actions and strongly denied involvement. The best-known example of this are the infamous ‘little green men’ who popped up everywhere. Lacking any unit insignia or other features that could link them to Russia made it possible for the Russian government to deny the claim they were in fact Russian Special Forces.[26] These actions can easily be categorized as a classical example of Russian military deception, or Maskirovka, but are they also evidence of the use of the more refined concept of RC? To answer this, the following question must be answered first: did the Russian Federation influence (use its ability to reflex and manipulate the filter of) Ukrainian and western governments with the intention to let them make the decision not to take action and thus do exactly what the Russians wanted them to do? It is argued that Russia manipulated Kiev’s and NATO’s sensory awareness of the outside world in the period leading up to the actual annexation of the Crimea.

The overall goal was not to paralyze their systems, but to alter their perception of reality by disguising the Kremlin’s real intentions (annexation of the Crimea). Kiev and NATO had to come to the conclusion that Russia would not invade the Crimea and that de-escalation was the best option, which was exactly what the Kremlin intended. This was achieved in various ways. First of all, Russian forces already present in Crimean naval bases were capable of seizing key points under the cover of deception. They also penetrated deeply and paralyzed a possible Ukrainian response (for example, by holding Ukrainian forces hostage within their own barracks). Russian military build-up along the eastern Ukrainian border, preceding the eventual annexation, was another factor. This did not only pin down Ukrainian units in those areas at a huge distance from the Crimea, but it also added to the confusion in Kiev and within NATO about the true scope and intentions of the Kremlin. The massive military build-up and sub-sequential snap-exercises[27] did not only add to confusion, but also deterred Kiev from taking any decisive action in the Crimea. [28] The afore-mentioned combination of Russian actions leads to the conclusion that RC was indeed applied regarding the annexation of the Crimea.

The success of the Russian Crimean campaign was astounding. In a matter of three weeks, and without a shot being fired, the morale of the Ukrainian military was broken and Ukraine surrendered all of its 190 military bases in the Crimea. This was achieved by less than 10,000 Russian troops (mostly naval infantry, and some airborne and Spetsnaz battalions) making use of the BTR-80 armoured personnel carrier as their heaviest combat vehicle. The Ukrainian forces totaled 16,000 and included mechanized formations with armoured infantry fighting vehicles, self-propelled artillery and tanks.[29]

Eastern Ukraine

The ongoing conflict in eastern Ukraine may also serve as an example of the application of RC within the context of hybrid warfare. The massive build-up of Russian forces that started back in 2014 along the Russian-Ukrainian border is still there, disguising the sending of troops across the border or providing weapons to separatists. It also offers a disguise for Russian forces operating from Russian soil, for example the launching of Remotely Piloted Aerial Systems (RPAS), artillery strikes in the Ukraine, or Electronic Warfare units jamming frequencies of Ukrainian units all originate from Russian soil.

People climb a Russian tank in Kiev during the opening of an exhibition of Russian weapons captured from pro-Russian rebels in eastern Ukraine. Publicly the Kremlin denies any involvement in the region. Photo ANP/AFP, S. Supinski

Publicly the Kremlin denies any involvement in eastern Ukraine, despite mounting evidence to the contrary. The evidence includes specific versions of fighting vehicles operating in eastern Ukraine which are exclusively used by Russian forces. It also includes pictures of damaged Russian tanks, which have sustained damage that can only be inflicted in actual combat due to mines, anti-tank missiles and other tanks. These pictures have been taken on Russian territory, when the tanks were being repaired within several kilometres from the Ukrainian border.

Disinformation targets public perception

There is also a large ongoing campaign using disinformation, which not only targets the population of the Ukraine and Crimea, but also the public in Russia itself. A recent publication from NATO’s Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence (StratCOM CoE) reports that the deception campaign is highly successful, stating that only 6 per cent of Russians believe that the war in eastern Ukraine continues due to the interference of the Russian leadership in the conflict by supporting the Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic.[30] However, what is more relevant for this article is that the disinformation also targets western and Ukrainian public perception, based on a specific strategic narrative which also has the purpose to divide the West. Russia makes use of different and sometimes conflicting economic interests of EU member-states regarding Russia. It also exploits the difference in views between New Europe (Eastern Europe) and Old Europe (Western Europe). Furthermore, Russia exploits historic paradigms, such as the Nazi occupation many countries endured during World War II. This is also the reason why there is such a strong emphasis on branding pro-Kiev movements as fascist and linking them to a fascist-friendly regime in Kiev.[31]

The following narratives are being used to target the West, the Ukraine and Russian society:

- Ethnic Russian minorities are suppressed in the Ukraine and in EU-countries;

- Russia is an enemy of the West and therefore the West tries to limit Russia’s global influence and power;

- The USA and other EU-countries organized the colour revolutions in a few post-Soviet countries that were anti-Russia oriented;

- Russia is a superpower and has to have the right to influence. The ‘objective’ sphere of its influence is the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS);

- Russia is a stronghold in fighting modern fascism. Everything identified as anti-Soviet or anti-Russian should be labelled as fascism;

- The western individualism is destructive. Collective consciousness is the traditional form of consciousness for Russians;

- The Russian Orthodox Church is the only right religion. Morality is dying in the West. Europe becomes ‘Gay-Europe’, which is illustrated by the many homophobic rants in Russian media and society;[32]

- The Russian World, the Russkiy Mir, is an alternative to ‘Gay-Europe’.[33]

The Russian Federation has several strategic objectives including preventing further expansion to the east by both NATO and the EU, and recreating a buffer zone between the Russian heartland and NATO. Until now Russia has succeeded in avoiding a strong and decisive action by either NATO or the Ukrainian military in eastern Ukraine and thereby contributed to the aforementioned two objectives.[34]

Application of RC in the Baltics

The conflict in Ukraine is taking place at the fringes of EU and NATO territory. Russia, however, is also being perceived as a threat to the NATO member states in the Baltics, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Russia’s aggressive stance includes attempts to activate Russian proxies (Russian ethnic minorities), simulated attacks by SU-24 fighters in the Baltic Sea on US navy vessels, cyberattacks, and threats to use nuclear weapons. The threat is being perceived as real in these states, especially in Estonia and Lithuania.

It is interesting to notice that, although there are large Russian-speaking minorities in all three states, they do differ in nature from the Russian minority in eastern Ukraine. For example, there is hardly any desire to join the Russian motherland among the Russian- speaking minorities. In fact, many of them consider President Putin an opportunist and they prefer to stay in the Baltics and be part of the EU and NATO. The biggest threat to the Baltics, therefore, comes from the ever-increasing numbers of Russian forces surrounding them. The threat lies not only in the numbers, but also in the quality of equipment of these units. The perceived threat already led to an Enhanced Forward Presence of NATO battlegroups.[35] Marcel van Herpen, director of the Cicero Foundation, says that Russian behaviour towards the Baltics fits within the framework of RC. He states that, just as is the case with the Ukraine, Russia attempts to redraw the map of Europe and reinstate a buffer zone between the ‘motherland’ and NATO by influencing decision-making processes in the Baltics and NATO.[36] A possible scenario which Russia hopes to achieve is to make NATO members inclined to think that de-escalation is the best option, which in fact would give the Baltic States the feeling they are being abandoned and will thus divide NATO.[37] It is even suggested that Russia will eventually invade the Baltics in Blitzkrieg style and, by deterring NATO, aim at slowing down a decisive response allowing Russia enough time to create an advantageous negotiating position.[38]

Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov addresses international security matters during a visit to NATO’s headquarters. Photo NATO

RC and eFP

The Royal Netherlands Army also participates in NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence (eFP), within the German-led multi-national battlegroup in Lithuania. Most countries participating in the eFP battlegroups have imposed restrictions on their contingents, in some cases including the restriction to stay in barracks except during organized tours.[39] The measures are largely a reaction to Russian information operations, discrediting NATO presence in the Baltic region and eastern Europe at every possible opportunity. Incidents involving NATO service members are, of course, exploited to the full extent by Russian media outlets like RT and Sputnik.[40] The Russian-speaking minorities in the Baltics largely depend on Russian-based news outlets and are easy targets for the Kremlin. But also, other western news outlets have a tendency to copy the Russian narrative, let alone social media where fake news narratives can go viral in an instant.[41]

Thus, it seems quite a sensible measure at first sight to avoid any risk of unwanted media coverage of misbehaving soldiers. A recent incident in August 2017, concerning intoxicated Dutch soldiers in Lithuania, is an example of what NATO wants to avoid.[42] Minimizing any risk of unwanted incidents can relatively easily be achieved by restricting freedom of movement of personnel, for instance by putting into effect a curfew, etc. However, by restricting the movement and visibility of personnel, NATO contingents are possibly more or less alienating their units from their environment. This development, in turn, might make it easier for Russia to continue its relentless stream of negative coverage regarding NATO in the very same countries, because people have a tendency to fear or distrust anyone they do not know. Furthermore, it is a fact that several negative stories about NATO contingents in the Baltics were completely made up, and could be categorized as fake news. One recent example concerns the German battlegroup commander in Lithuania being photographed with a Russian ‘spy’ in the Red Square in Moscow; another the alleged rape of a young girl by two German servicemen.[43]

Restricting the freedom of movement of NATO service members does not at all prevent the Russian government from releasing false stories about misconduct. Alienating NATO contingents from their environment by imposing restrictions on freedom of movement could be exactly the outcome Russia has been aiming for all the time. So, it is possible NATO itself is unwillingly creating a new example of successful Russian implementation of RC against the alliance for historians to reflect upon later.

Conclusion

The aim of this article is to provide an insight into the concept of RCT, its application in the past, present and future and how it effects NATO and the Netherlands Armed Forces. RC essentially influences an adversary’s decision-making process with specifically prepared information and induce him to make decisions that are in fact predetermined by the originator of the prepared information. Over more than a half-century the concept has been used frequently. During the Cold War it was used by the Soviet Union to influence NATO and the USA in the nuclear arms race, while in the early 90s Russia used it also to target Russian civilians and politicians to prevent a coup d’état. In the recent past RC has been used by the Russian Federation within the framework of hybrid warfare, for example in the Crimea and eastern Ukraine. There is also evidence of the use of RC in the Baltic region at this very moment.

Application of RC in the Ukraine and the Baltics likely serves a common goal: redrawing the maps of Europe and creating a more favourable situation for the Russian Federation, recreating (in some fashion) a strategic buffer between the Russian heartland and NATO. In the Baltics efforts are made to discredit NATO as an alliance and NATO troop contributions specifically as part of a bigger plan to influence decision-making within the Baltics and NATO.

Implications for the Netherlands Armed Forces and NATO

RC, although a Russian concept, appears to be of great relevance concerning the (Dutch) doctrinal basics regarding the maneuvrist approach. It is therefore recommended that the Dutch armed forces, in a broader framework of NATO, look into applying the mechanisms of RC itself to target the conceptual and mental component of opponents. In order to be able to do this, the Netherlands Armed Forces first have to get a real understanding of its possible opponents and learn to let go of western paradigms (this without implying that the end justifies all means). In order to begin to understand an adversary, it is relatively easy to start reading open source publications on for example military doctrine. A note of caution in this regard, however, was given by the Russian General A.F. Klimenko in 1997, claiming that the Russian Federation put false information into official military doctrine, with the purpose of exploiting the carefully cultivated misconceptions by applying RC at the appropriate time.

Regarding the application of RC in the Baltics, NATO has to look into ways to counter RC applied by the Russian Federation. This includes amongst others countering negative narratives from Russian media outlets by providing NATO’s narrative. On the other hand, showing to the public that eFP service members who misbehave are getting punished is possibly more effective in this regard than trying to avoid any risk at an incident. If the Netherlands and other NATO members want to avoid being deceived by the mechanics of RC, they will first have to understand themselves and especially how they are assessed by the Russian Federation. If they are able to see themselves through the same glasses as the institutions that target them by using RC, they will be better able to identify possible threats. Furthermore, it is essential to be critical every time a decision is made that seems to be the only logical choice, because RC preys on logical reasoning.

While reading this article, we could get paranoid because it appears that we cannot even trust one’s own logical reasoning anymore. The harsh reality is that one must indeed question one’s own decisions to avoid being manipulated within the context of RC. It would be wise to ask oneself over and over again the question with an historical ring regarding the outcome of decisions to be made: cui bono?

* Christian Kamphuis is a major in the Royal Netherlands Army and is currently working at the Land Training Center, part of the Education and Training Command. This article was written as a spin-off from the doctrinal bulletin on the Russian Independent Motor Rifle Brigade, which the author wrote on behalf of Commander Land Training Center.

[1] H. Bouwmeester, Behold: Let the Truth Be Told—Russian Deception Warfare in the Crimea

and Ukraine and the Return of ‘Maskirovka’ and ‘Reflexive Control Theory’, in: Ducheine, P., Osinga, F., NL ARMS 201, Winning Without Killing: The Strategic and Operational Utility of Non-Kinetic Capabilities in Crises, Den Haag: T.M.C. Asser Press (2017) 125-155.

[2] H. Bouwmeester (2017).

[3] H. Bouwmeester (2017).

[4] H. Bouwmeester (2017).

[5] T.L. Thomas, ‘Russia’s Reflexive Control Theory and The Military’, in: Journal of Slavic Military Studies 17 (2004) 237–256.

[6] V.A. Lefebvre, op cit in: Shemayev, V.N., ‘Reflexive control in socio-economic systems’, in: Information & Security. An international Journal No. 22(2007) 28-32.

[7] T.L. Thomas, ‘Russia’s Reflexive Control Theory and The Military’, in: Journal of Slavic Military Studies V7 (2004) 237–256.

[8] Giles, K., Handbook of Russian Information Warfare, Rome: NATO Defense College (2016) 19.

[9] Thomas, T.L., Kremlin Kontrol, Ft Leavenworth: Foreign Military Studies Office (2017) 175-197.

[10] V. Shemayev (2007).

[11] T. Selhorst, ‘Russia’s Preception Warfare’, in: Militaire Spectator 185 (4) (2016) 148-164.

[12] C. Kasapoglu, Russia’s renewed military thinking: non-linear warfare and reflexive control, Rome: NATO Defence College (2015).

[13] T. Thomas, The Evolving Nature of Russia’s Way of War, in: Military Review, July-August 2017.

[14] C. Kasapoglu (2015).

[15] T. Thomas (2017) 175-197.

[16] V. Shemayev (2007).

[17] T.L. Thomas, ‘Russia’s Reflexive Control Theory and The Military’, in: Journal of Slavic Military Studies 17 (2004) 243.

[18] L.W. Grau, How Russia Fights, Ft Leavenworth, KS: Foreign Military Studies Office (2016) 50-51.

[19] T.L. Thomas, ‘Russia’s Reflexive Control Theory and The Military’, in: Journal of Slavic Military Studies 17 (2004) 243-246.

[20] T.L. Thomas, ‘Russia’s Reflexive Control Theory and The Military’, in: Journal of Slavic Military Studies 17 (2004) 248-249.

[21] Doctrine Publicaties 3.2, Landoperaties. Amersfoort: Land Warfare Centre (2014) 81-89.

[22] T.L. Thomas, ‘Russia’s Reflexive Control Theory and The Military’, in: Journal of Slavic Military Studies 17 (2004) 252-253.

[23] A. Baranov, ‘Parade of Fakes, Moskovskii komsomolets (Moscow Komsomol), May 8, 1999, 6, as translated and entered on the FBIS webpage, May 11, 1999.

[24] See http://www.independent.co.uk/news/moscow-paraded-dummy-missiles-1185682.html.

[25] See https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-players-1993-crisis/25125000.html.

[26] The United States Army Special Operations Command, Little Green Men, Carolina: The United States Army Special Operations Command (2016) 21-40.

[27] A snap-exercise includes units being deployed without any prior warning given, to test their operational readiness in case of emergency. Sometimes units only have to move to an assembly area, but sometimes they have to participate in in exercises after arriving at the assembly area.

[28] T. Bukkvol, Russian Special Operations Forces in Donbass and Crimea, Oslo: Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (2016).

[29] C. Kasapoglu (2015).

[30] V. Ogrisko, Russian information and propaganda war:some methods and forms to counterreact, Riga: NATO Stratcom CoE (2016).

[31] J. Bērziņš et al, Analysis of Russia's Information Campaign against Ukraine. Riga: NATO StratCom Centre of Excellence (2015).

[32] J. Rutenberg, ‘RT, Sputnik and Russia’s New Theory of War’, in: New York Times Magazine, 13 September 2017. See https://nyti.ms/2eUldrU.

[33] V. Ogrisko (2016).

[34] J. Bērziņš et al (2015).

[35] J.E. Noll, ‘De Baltische Staten, de Russische minderheid en de verdediging van de NAVO’, in: Militaire Spectator 186 (2017) (4) 169-183.

[36] See https://www.baltictimes.com/russia_s_nuclear_blackmail_and_new_threats_of_covert_diplomacy.

[37] M.H. van Herpen, Russia's nuclear threats and the security of the Baltic states (Maastricht: Cicero Foundation, 2016).

[38] See http://www.fpri.org/2017/06/natos-baltic-defense-challenge/#.WT7tJoyh6fU.twitter.

[39] See http://www.nationalpost.com/m/wp/news/canada/blog.html?b=news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/matthew-fisher-how-canadian-commanders-will-use-hockey-to-keep-soldiers-safe-from-russian-honey-pots.

[40] See https://medium.com/dfrlab/russian-narratives-on-natos-deployment-616e19c3d194.

[41] See https://jamestown.org/program/russian-fake-news-operation-seeks-generate-baltic-opposition-nato-presence.

[42] See https://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nederland/nederlandse-militairen-weggestuurd-uit-litouwen-na-dronkenschap-en-mishandeling.

[43] See https://www.thelocal.de/20170217/german-army-battles-fake-news-campaign-of-rape-reports-in-lithuania.