Donald J. Trump came to office as a disruptive president, who campaigned on economic protectionism and America First nationalism. He further vowed to undermine the Washington foreign policy establishment through the prodigious use of Executive Orders. While we may have been spared former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon’s goal of bringing down the institutions of the state, the world has not emerged unscathed after nearly four years of Trump in the White House. As Americans prepare to cast their vote in the November elections, a look back on Trump’s foreign policy as well as a look ahead is a valuable exercise. This article first considers how Trump affected U.S. foreign policy and second what are the most important foreign and security issues that loom over the horizon, for whomever wins the election.

Dr. R.N. Haar*

U.S. President Donald Trump walks along the U.S.-Mexico border in Arizona. Photo White House

Regrettably, the first few tumultuous months of the Trump policy making machine set the norm for conduct. Moreover, the administration continued to lose competent staff, who were replaced by loyalists or persons who did not have relevant government experience. Those individuals who European leaders hoped would establish a more standard foreign policy, such as Defense Secretary James N. Mattis, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, and National Security Adviser (NSA) Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, all left by January 2019. Their replacements were chosen for allegiance to Trump over competency. For example, White House Chief of Staff John Kelly was replaced with Mike Mulvaney, who indicated he wanted ‘to let Trump be Trump’, and Tillerson was replaced by Mike Pompeo, who as CIA director had advocated pro-Trumpian positions even against the intelligence community that he led.

Thus, by midway of Trump’s term, the so-called ‘adults’ had not achieved their preferred policy of preserving and strengthening the United States’ alliance system before they left office. Trump’s strategy of regularly undermining his own officials meant that U.S. policy suffered from a credibility gap between the stated plan and what the president said and did. America’s trustworthiness and reputation greatly declined.[1] For example, according to the 2018 Report on Rating World Leaders by Gallup, approval ratings of U.S. leadership dropped 40 points or more in places such as Portugal, Belgium, Norway and Canada.[2]

By start of the fourth year of his term, Trump’s bullying tactics took on added vim when he announced the withdrawal of roughly 12,000 U.S. troops stationed in Germany. The fact that some of the soldiers were moved next door to Belgium, along with their command, made clear that the withdrawal was to punish Germany for its under-investment in defence and perceived unfair trade practices.[3]

On the positive side, during Trump’s time in office, spending for America’s military presence in Europe actually increased under the European Deterrence Initiative and the Trump administration’s official documents, including the National Security Strategy (NSS), the National Defense Strategy (NDS) and the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), all restate America’s understanding of the value of allies. Trump also established a new Space Command, which has operational control of U.S. space assets used above 100 kilometres. Trump further envisioned the establishment of a Space Force, the first new military service since the Air Force was created in 1947. The Space Force will focus on war-fighting operations and defending space assets.

What does this mean for the world after 3 November?

Whether the world likes it or not, some aspects of Trumpism are here to stay. If former vice president Biden wins, a degree of internationalism will return, but he must consider the fact that the U.S. began retreating from its global leadership role when he was vice president. Although Biden articulated the idea that his presidency would return to internationalism,[4] at the Munich Security Conference in February 2019, the truth is that the U.S. had already grown weary and inward looking as it tired of fighting endless wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East.

Moreover, America had already begun to diminish its support of the international system that it put in place after the Second World War before Trump entered the White House. In fact, one could argue that Trump’s capturing the presidency as the insurgent candidate in 2016 is symptomatic of a general revision in thinking about U.S. global leadership and the role of global institutions.[5] A paradigm shift that would include the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union. Thus, Biden must consider popular sentiments that express a loss of faith in international organizations (IO), like the EU or the UN, with publics today believing that IOs are too distant, too intrusive and ultimately too ineffective.

U.S. President Donald Trump addresses American troops at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan. Photo White House

Add to this that the Democratic Party itself is shifting towards a more Trumpian view of the world. The other two Democratic candidates that voiced views on foreign policy, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, both see Trump not as a historical aberration but as the outcome of a long historical decline in the U.S.’ role on the world stage.[6] Moreover, the Democratic Party’s new strategic thinkers also argue that Trump is right.[7] These new voices advocate restraint, something that a President Hillary Clinton was sure to find deplorable.[8]

Biden’s January 2021 agenda

If Biden were to win in 2020, there are a number of more traditional security challenges that he must address, including a new nuclear arms race, nuclear proliferation in places like Iran, emerging threats from cyberwarfare, conventional weapons being controlled by artificial intelligence, and new hypersonic weapons. North Korea also remains a threat that Trump’s summitry diplomacy did nothing to allay.

While all of these more traditional security threats will still be on the agenda of whoever takes the oath next January, the most important issue for a newly-elected President Biden will be the Covid-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, the absence of any U.S. leadership to combat the virus in Trump’s first term created opportunities for nationalism, including an international blame game, interstate fights over personal protective equipment (PPE) and fights over exclusive access to vaccines. In past epidemics, the U.S. played a unifying role — one that utilized relevant international organizations, such as the G7 and the World Health Organization (WHO).[9]

Although a return to internationalism will not be easy, Biden’s administration could go some way in addressing the devastating human cost of the pandemic by not shirking global responsibilities and not spurning relevant IOs. Trump’s stance could even create opportunities for Biden to push for reform of the WHO. Biden could then focus on pandemic preparedness by following science and listening to experts. The virus exposed decades of underfunding or the misallocation of resources not only in the U.S. healthcare system but in many national health care systems. This means that the U.S. could set a good example by investing in medical workers and emergency equipment and increasing its funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) at the domestic level and the WHO in its work internationally.

Global economy

The second most important issue for a Biden presidency is linked to the first: the economic damage wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic to the global economy will be worse than the Great Depression of the 1930s. The U.S. jobless rate in the wake of the pandemic essentially wiped out all the job gains since the last recession in 2008, when Barack Obama started his first term as president. But therein lies one advantage that a President Biden has in addressing the problem of a severely weakened global economy: as Obama’s vice president, Biden has some experience in dealing with a deep-down turn of the U.S. and global economy. In fact, Biden was personally responsible for administering the 787 billion dollar stimulus that Obama launched to combat the deepening recession.[10]

Experience counts because finding the right solutions to bring about economic recovery will be complex and solutions must be innovative. The most vulnerable countries in the global system will need support; the U.S. could be a leader in reanimating elements of the liberal world order, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that could go some way in finding global solutions. The U.S. retains a potentially powerful economy that has influence.

Finding the right solutions to bring about economic recovery will be complex and solutions must be innovative. Photo White House

It also retains larger amounts of hard and soft power — certainly more than its main global rivals — that is readily applicable to the global economy. For instance, the U.S. Federal Reserve acts as the world’s central bank, even if it does not want to assume this role, by stabilizing the dollar. A Biden administration could utilize America’s advantages in the global financial system to trigger and support a global economic recovery. This could also mean pushing for reform of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which has become increasingly dysfunctional.

Climate change

Focusing on climate change, along with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreement with Iran, can be placed on Obama’s accomplishment list. For example, in 2014, a year before the Paris climate summit, Obama brokered a deal with China — a G2 agreement of the world’s two biggest emitters of CO2, to reduce their greenhouse gases. But, since the past five years have been the hottest five on record (with 2016 being the hottest) and since climate change is the result of cumulative emissions of carbon dioxide, major challenges associated with climate change will remain for the foreseeable future.[11]

In this case, Biden must build from what the Obama administration started by redirecting climate policy toward a new set of multilateral arrangements and repairing relations with international institutions that combat global warming. Additionally, a Biden administration should re-join the Paris Climate Accords.

Domestically, Biden could invest in renewables and energy efficiency. Add to this that no matter who is in the White House, the next administration needs to make clear to the American public that climate change has the potential to hit the U.S. and global economy with future shocks on par with the Covid-19 pandemic. In fact, Trump’s executive branch concluded in 2018 that without rapid reductions in greenhouse gases, the warming of the earth’s temperature will kill thousands of Americans annually.[12]

China

The first three issues are global problems that require international cooperation — necessitating global teamwork that a new U.S. administration could lead and coax other nations in the right direction. The fourth issue relates to deep structural shifts that are reshaping global politics. China’s rise in the global pecking order and its emphasis on sovereignty contributes to a back-to-the-future realpolitik world that a Biden administration cannot ignore.

As China seeks to translate its economic rise to political power, it challenges the structure of the post-war system as well as the Western values and institutions that underpin this system. In the wake of the U.S.’ slow and poor response to Covid-19 and the Trump administration’s clear unwillingness to organize an international effort to fight the disease, as it has in past epidemics, China further saw opportunities to burnish its soft power and its image as a world leader.

It does not help that Trump’s trade war with China has not altered any of the institutional practices that it was meant to stop while at the same time Trump’s executive orders, which demand American firms unwind their commercial relations with companies such as ByteDance and WeChat, could lead to losses in the trillions for global technology firms. Before the pandemic, it was estimated that Trump’s trade war with China already cost 300,000 American jobs.[13] This means that Trump’s trade policies towards China are not only not working, but also that they are costly to American and global economies.

Thus, Biden will likely enter the White House facing, one the one hand, a confident China that believes the pandemic and the resulting global recession are marking a geopolitical reordering that is supporting China’s rise, and on the other hand, a fearful China that may see retaliatory measures, such as selling its 1.1 trillion dollar worth of American treasury bonds, as a viable option in its economic war with the U.S.[14] A Biden administration could respond to this combination of swagger and fear by emphasising that from a number of perspectives China’s global structures are not as desirable as the U.S.’ tried and tested ones. In an age when a virus can stall economies, overwhelm excellent health systems and kill tens of thousands of their citizens, a Biden administration could be forthright in pointing out to its allies that they cannot depend on an autocratic China.

Russia

Russia’s re-emergence as a player of consequence on the international stage coincides with president Vladimir Putin’s adventurism in Crimea and eastern Ukraine in 2014. A revanchist Russia that further decided to support Bashar al-Assad in Syria strained U.S.-Russian relations, with Obama resorting to the path of least resistance. Add to this that after Trump’s withdrawal of forces from Iraq and Syria, Putin emerged as the kingpin in the Middle East and you get another agenda item for a would-be President Biden to address: how to deal with an assertive Russia.

The first step in Biden’s ‘reset’ with Russia would be to extend the New START treaty, which was brokered by Obama and limits U.S. and Russian strategic long-range nuclear arsenals. Without an extension, New START could go the way of the INF Treaty (the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces) and collapse. While cheating undermined the INF, there is no indication that Russia is similarly hiding activities and weapons systems that fall under New START specifications. To the contrary, Russian officials even demonstrated new delivery systems, like a hypersonic glide vehicle, to American inspectors.[15] Moreover, a failure to extend New START, which can be done by mutual agreement without involving Congress, would certainly open the way for a new nuclear arms race.

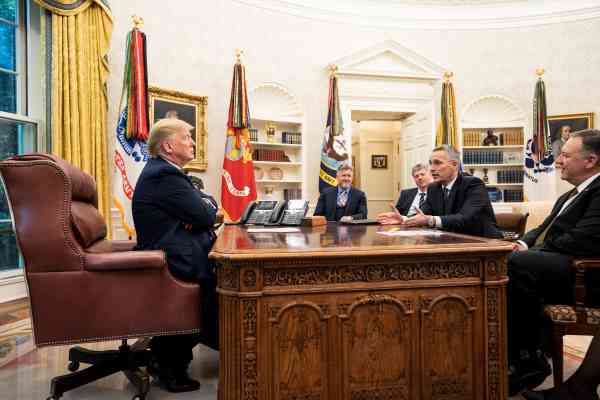

U.S. President Donald Trump meets with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. Photo White House

The second step in dealing with Russia that a Biden administration could take is to rebuild transatlantic ties in order to present a unified front to Russia. Putin is surely delighted that America’s relations with its European allies, in particular Germany, are at a low. Trump’s transactional view of alliances combined with what Richard Haass, the president of the Council on Foreign Relations, describes as Trump’s ‘Withdrawal Doctrine’, creates divisions between allies that Putin could have only fantasied about before January 2017.

Trump’s dismantling of global institutions also creates windows of opportunity for Putin to act with impunity. A wide latitude that allows Putin to be repeatedly accused in the UN Security Council of committing war crimes in Syria but still have a cosy one-on-one date in Helsinki with the ‘President of the Free World’. Rather than give him a pass on his brutality and his penchant for poisoning his enemies, Biden could hold Putin accountable for his crimes on the world stage.

A Trump second term

All of the above agenda items will certainly exist in a Trump second term, whether he chooses to deal with them or not. If Trump pulls off another surprise win, Europeans must prepare for a further acceleration of the decline in the relevance of international organizations and the foundations of the post-war international order.[16] Trump will continue to emphasise the quantitative with little consideration of the qualitative aspect of America’s alliances.

However, there may be some good that comes out of this policy stance, since Trump has put his finger on a real issue: the over-reliance of NATO allies on subsidizing their security and defence. Thus, one positive of a Trump second term could be that Europeans finally come to realize that they can no longer avoid a serious appraisal of the transatlantic relationship and their own territorial defence. The fact that as many as nine members met the two per cent threshold of their GDP in 2019 is one indication that European states are moving in that direction.

In other agenda items, Trump’s zero-sum view of the world will mean that he continues to ignore the dangers of climate change and continues to undo regulations designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. He will also push for such measures as opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in northern Alaska to oil and gas development, despite the fact that two-thirds of Americans oppose drilling in the reserve.[17]

If Trump captures a second term, the world will also remain confounded and confused when following and interpreting the Twitter-in-Chief. Unfortunately, Trump’s challenge to American values, his coddling of America’s adversaries and his subjugating of U.S. interests to his personal benefit, will likely endure. The most recent example of indulging adversaries was Trump’s response to revelations of a Russian-backed bounty program to kill coalition troops in Afghanistan. While members of Congress in both parties expressed outrage and demanded to know if the Taliban had in fact killed troops for Russian money, Trump did not call for an investigation into the allegations.

Finally, if Trump wins a second term, the new Congress, like the old, will value alliances more than the administration and it will continue to push for robust policies towards authoritarianism more than the president does. Many Republicans in Congress will also continue to have significant foreign policy disagreements with the president over topics such as sanctions on Russia.

What changes and what stays the same

The electoral environment of November 2020 is partly different and partly the same as in November 2016. Four years ago, the American electorate embraced candidates who openly waged war on their own parties. Certainly, Trump secured the Republican nomination by disagreeing with his party’s mainstream members on many core issues. The Democratic Party had its own insurgent, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who did not win the primary competition but whose popularity, like Trump’s, emerged from disagreeing with the traditional Democratic Party on key policy stances. Both Trump and Sanders tapped into the discontent felt by a sizable segment of the American electorate that experienced a crisis of confidence in government and leadership in the wake of the 2007-8 financial crisis.

U.S. President Donald Trump delivers remarks prior to the departure of the USNS Comfort, a U.S. Navy hospital ship. Photo White House

Today, the U.S. electorate is again, or perhaps still, expressing political cynicism and anti-establishment fervour. However, current anti-establishment passion is partly the result of a renewed sense of urgency in the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of George Floyd’s death and the economic, cultural and social effects of dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2016, agitations meant America embraced Trump and Sanders but not Hillary Clinton, the traditional candidate picked by Democratic Party professionals. Since Joe Biden is as a traditional candidate as they come, he may have difficulties in connecting with the anti-establishment mood that currently pervades the American electorate, giving Trump another win.

Covid-19 is a transformative event; past comparable global events resulted in a world that looked quite different on the other side of the crisis. No matter who is elected by Americans this November, the urgency of the global agenda will not go away. The terrible death toll and the economic shock wrought by Covid-19, as well as the looming catastrophic threat posed by climate change, necessitate a coherent response from the ‘leader of the free world’. Whether it is Biden or Trump, hopefully, he will show the right mix of courage and pragmatism to shape the other side of the crisis in ways that are good for global security and American foreign policy.

* Dr. Roberta N. Haar is Professor of Foreign Policy Analysis and Transatlantic Relations at Maastricht University.

[1] ‘NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist Poll Results January 2018’. See: http://maristpoll.marist.edu/nprpbs-newshourmarist-poll-results-january-2018/.

[2] Julie Ray, ‘World’s Approval of U.S. Leadership Drops to New Low’, Gallup News, 18 January 2018. See: http://news.gallup.com/poll/225761/world-approval-leadership-drops-new-low.aspx.

[3] Colm Quinn, ‘Trump to Pull U.S. Troops From Germany’, Foreign Policy, 30 July 2020. See: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/30/trump-explains-us-troop-exit-from-germany-suckers/.

[4] Joe Biden, Speech at the Munich Security Conference 2019. See:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w6faT3VOHgs.

[5] Roberta Haar, Is the Trump phenomenon a Symptom or a cause for shifts in U.S. foreign policy? Maastricht University, 30 January 2020. See: https://doi.org/10.26481/spe.20200130rh.

[6] Bernie Sanders, ’Ending America’s Endless War: We Must Stop Giving Terrorists Exactly What They Want’, Foreign Affairs, 24 June 2019. See: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2019-06-24/ending-americas-endless-war ; Elizabeth Warren, A Foreign Policy for All: Strengthening Democracy—at Home and Abroad’, Foreign Affairs 98 (2019) (1). See: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2018-11-29/foreign-policy-all.

[7] Richard Fontaine, Loren DeJonge Schulman, Emma Ashford, Hal Brands, Jasen Castillo, Kate Kizer, Rebecca Friedman Lissner, Jeremy Shapiro, and Joshua Itzkowitz Shifrinson, New Voices in Grand Strategy, Center for a New American Security, 11 April 2019. See: https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/new-voices-in-grand-strategy.

[8] See also, Stephen Walt, ‘Is the Blob Really Blameless?’, Foreign Policy, 22 September 2020. See: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/22/walt-gavin-liberalism-foreign-policy-blob-really-blameless/.

[9] ‘U.S. Response to the Ebola Epidemic in West Africa’, The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, 16 September 2014.

[10] ‘Biden to oversee stimulus implementation’, UPI, 23 February 2009. See: https://www.upi.com/Top_News/2009/02/23/Biden-to-oversee-stimulus-implementation/61741235422390/?ur3=1.

[11] ‘Assessing the Global Climate in 2019’, National Centers for Environmental Information, 15 January 2020. See: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/news/global-climate-201912.

[12] David Reidmiller (ed.), Fourth National Climate Assessment, U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2018. See: https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/1/.

[13] Mark Zandi, Jesse Rogers, and Maria Cosma, ‘Trade War Chicken: The Tariffs and the Damage Done’, Moody’s Analytics, September 2019. See: https://www.moodysanalytics.com/-/media/article/2019/trade-war-chicken.pdf.

[14] ‘The nuclear option’, in: The Economist, 15 August 2020, 52-53.

[15] Joshua Schwartz and Christopher Blair, ‘The US Doesn’t Need a New New START; There is no reason to believe that withdrawing from the current one would improve U.S. security’, DefenseOne, 14 February 2020. See: https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2020/02/us-doesnt-need-new-new-start/163132/.

[16] Ben Rhodes, ‘The Democratic Renewal. What it Will Take to Fix U.S. Foreign Policy’, in: Foreign Affairs 99 (2020) (5). See: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-08-11/democratic-renewal.

[17] Matthew Ballew, Anthony Leiserowitz, Seth Rosenthal, John Kotcher, and Edward Maibach, ‚Americans oppose drilling in Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’, Yale University and George Mason University, 26 September 2019. See: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/americans-oppose-drilling-arctic-national-wildlife-refuge-2019/.