After World War II with lies, half-lies, omissions and distortions of the truth former General Walter Warlimont created his own myth of innocence. His hierarchical chiefs, Generals Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl, were hanged for their participation in the atrocities of the Third Reich, among them the execution of the so-called Kommissarbefehl during the war against the Soviet Union. Warlimont denied involvement and responsibility and wrote a book in which he underlined his status as on onlooker. Convicted to life in prison at the Nuremberg Trials, Warlimont was already released in 1954. The Cold War proved to be a golden era for former officers to spread the myth of a ‘clean’ Wehrmacht.

The history of the German Wehrmacht does not end in 1945 with its demise at the hands of the Red Army and the other allies. After the war the historical debate about the role and actions of the Wehrmacht became part of Germany’s ‘Vergangenheitsbewältigung,’ its road to finding a way to deal with its past. Jonathan Bach and Benjamin Nienass note that ‘the German memory landscape is saturated with claims of innocence.’[1] The Wehrmacht has long laid claims to innocence from atrocities, crimes against humanity, participation in the Holocaust and preparation of offensive war, in spite of the fact that its leaders were convicted of those very crimes at Nuremberg. Which begs the question: how does one claim innocence in the face of convictions and overwhelming evidence?

In this article I will analyse General Walter Warlimont’s career as a case in point. He is a typical example of a Wehrmacht officer who claims innocence. For five years he worked at the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW). His hierarchical chiefs, Generals Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl, were hanged for their participation in the atrocities of the Third Reich. Yet Warlimont claims he was not an agent but a mere onlooker, a passer-by, who just happened to work at a place where atrocities and genocide were planned, but who never had any real involvement in those things, let alone responsibility for them.[2] This is audacious if nothing else, in particular because he signed one of the most flagrantly criminal orders of the Wehrmacht, the Kommissarbefehl, the order to shoot Soviet political officers (Kommissars) on sight after capture, denying them the rights they had as prisoners of war under the Geneva Convention.

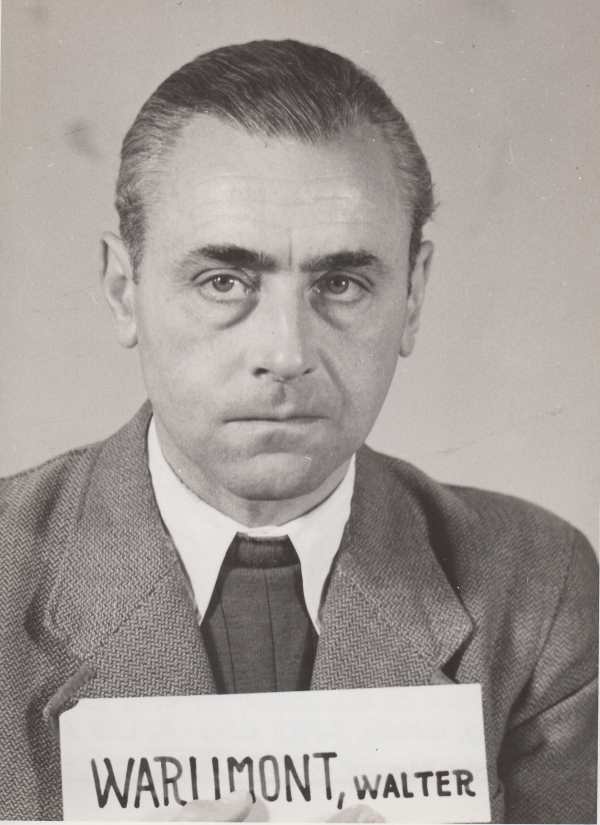

Walter Warlimont photographed before the Nuremberg Trials: the General typically upheld the ‘clean’ Wehrmacht myth. Photo US National Archives NextGen Catalog

Warlimont is one of many German Generals whose post-war reputations, and sometimes careers, were rooted in the ‘clean’ Wehrmacht myth. They maintained that the Wehrmacht was a politically neutral, professional army, and that atrocities were the exclusive work of the Waffen-SS and Einsatzgruppen, perpetrated on the orders of Hitler and a small group of criminals like the Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler. Perhaps it gave them a clear conscience. It certainly gave them the opportunity to participate in historical research as consultants, give interviews, participate in book projects and documentaries, write books, and in some cases pursue careers in the new Bundeswehr. It was not true however. The realities of the Cold War and the need to create a strong German army stifled debate on the role of the Wehrmacht for a long time and was an important factor in the persistence of the ‘clean’ Wehrmacht myth. Not because the facts were not there, but because no one was really or sufficiently interested in them.

Be that as it may, the guilt of Warlimont and others has been established beyond doubt at Nuremberg and the subsequent Nuremberg Trials. What makes the case of Warlimont interesting is how he managed to present himself more as a victim than as a perpetrator. The reasoning, the use and abuse of evidence is important to look at and to understand. Not just because it sets the historical record straight but also because war crimes and atrocities are not a thing of the past. Understanding one perpetrator’s myth and history may also help us in the present and the future. Especially now, when history becomes more and more contested and becomes an element in political narratives and hybrid warfare.

In section 1 of this article (Warlimont’s claim of innocence) I will first present how Warlimont liked to present himself after the war. Then, in section 2 (Behind the myth) I will take a look at the things Warlimont liked to leave out or misrepresent (notably: in section 2.1 his membership of a Freikorps, his misrepresentation of the atmosphere in the German army under Hitler in section 2.2, and in section 2.3. the precise role and task of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht especially in Operation Barbarossa (2.3.1) and in preparing criminal orders (2.3.2.). In section 3 I will look at his conviction at Nuremberg. Section 4 is the conclusion.

Warlimont's claim of innocence

General Walter Warlimont presented himself after the Second World War as a professional Wehrmacht soldier, who was not involved in politics, and who disliked Hitler and his ideals. Warlimont was a staff officer[3] in the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht. The OKW was the replacement of the Ministry of Defence. In 1938 Hitler forced the then Minister of Defence Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg out on a pretext and appointed himself supreme commander. For each of the armed services a department was established (Oberkommando des Heeres, der Luftwaffe und der Kriegsmarine). Coordinating the work of the three departments was the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, commanded by General Keitel. The most important department was the operations staff (Wehrmacht-Führungsamt, under General Jodl). Warlimont was Jodl’s second in command, and chief of the operations staff (Landesverteitigungsführungsamt). He was thus formally three steps removed from Hitler.

In his published memoir about his time in the OKW Warlimont deplores the sacking of Von Blomberg and Hitler’s new role. Under Blomberg, he asserts, the Defence Ministry was a military bureau with its own professional responsibilities against the leader of the state. The OKW in its new configuration was more like the military bureau of Hitler the politician.[4] Warlimont characterises the new situation as a power grab (Machtergreifung) of Hitler,[5] who abused the OKW for his political goals, supported in this by Keitel and Jodl.[6] ‘Power grab’ and ‘abuse’ are strong terms that should indicate that Warlimont was professionally hurt when politics entered the Wehrmacht. Hitler’s goals are described as ‘political,’ which stands opposed to ‘professional military’ in Warlimont’s account.

Professionalism was the main claim of innocence. Warlimont acknowledged that terrible atrocities had taken place, but these were the work of Hitler, the SS and some officers like Keitel and Jodl who had entered into a sort of Faustian pact with Hitler to benefit their careers. The Wehrmacht, the professional army, was by and large innocent of the atrocities of the Second World War, because it was only occupied with the professional and politically neutral use of military power. As Warlimont wrote in his memoir: ‘[D]er deutsche Soldat des zweiten Weltkriegs [hat] auch im Osten trotz unerhörter Belastungen – von eigener ‘höchster Stelle’ wie von seiten des Feindes – seine traditionelle Haltung zu wahren gewusst.’[7]

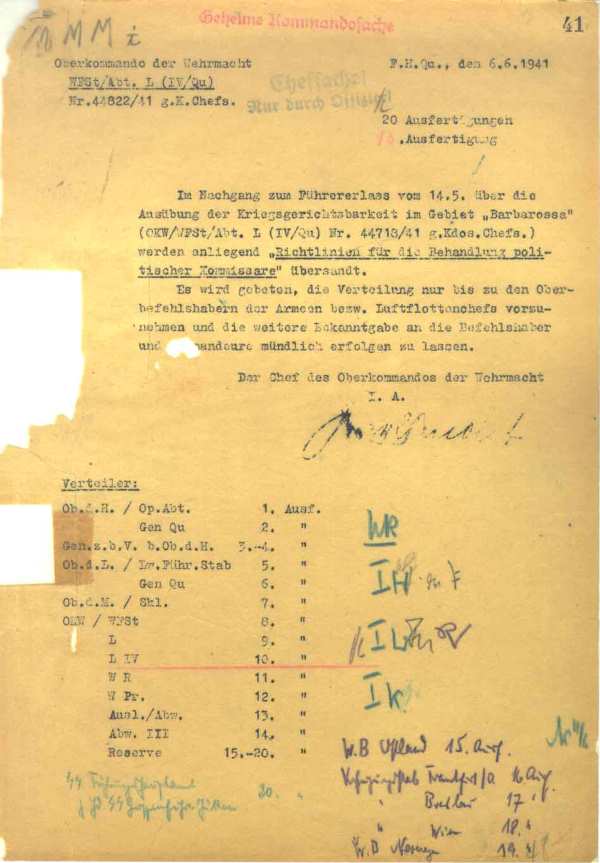

In June 1941, Warlimont signed an order that distributed the Kommissarbefehl among the highest Army and Air Force Generals; from there on, the Kommissarbefehl was to be forwarded only orally. Source: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung

Behind the myth

Warlimont was, to say the least, not very informative about his career. His tactic at Nuremberg and later was to acknowledge what could not be denied, downplay the significance of it and be silent about the rest. That is likely also why his memoirs start at the moment that he is a Colonel. But his early career is telling because it reveals his true sympathies.

The Freikorps

According to his testimony[8] at the OKW trial in Nuremberg Warlimont was born in 1894 in Osnabrück, to parents who came from the frontier area with Belgium.[9] He went to school (Humanistic Gymnasium) in that same city, and after his final exams he entered an artillery regiment in Strasbourg (the Alsace region belonged to Germany after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71). When the Great War erupted he was a young Lieutenant in the artillery, and he spent the war at the front. In his testimony he notes briefly what he did after the war: ‘A short while after the war I entered the Free Corps of General Merker (sic!) which was stationed in central Germany and participated particularly in the suppression of communistic insurrections. When the 100.000 man army was formed [the Reichswehr, JH], I was taken over into an artillery regiment with a rank of first lieutenant.’[10]

Warlimont quickly passes over a significant biographical detail: his membership of a Freikorps. Many Wehrmacht officers had been members of a Freikorps, and it makes their later claims of political neutrality significantly less believable. The Free Corps Maercker (wrongly spelled in the court transcript) was, as most of them were, a right wing anti-Semitic militia, and it reveals quite a lot about Warlimont’s political convictions as a young man that he was a member of such a militia.

The Freikorps were militias of ex-servicemen, although many youngsters who had missed the First World War because of their age also got their first fighting experiences in the Freikorps.[11] They were well organized, uniformed, armed, and extremely violent. They formed the core of the counterrevolution when Germany was undergoing a wave of communist uprisings in 1918 and 1919, which they brutally suppressed: ‘(Karl) Liebknecht and (Rosa) Luxembourg were murdered,[12] and (communist) revolutionaries were mown down or summarily executed in a number of German cities,’ historian Richard Evans has written.[13] The members of the Freikorps were young men, a large part of whom had seen unspeakable violence in the trenches of Flanders and France. It is worth quoting Evans at length here: ‘Many of the Free Corps’ leaders were former army officers whose belief in the ‘stab-in-the-back’ myth was unshakable. The depth of the Free Corps’ hatred of the Revolution and its supporters was almost without limit. The language of their propaganda, their memoirs, their fictional representations of the military actions they took part in, breathed a rabid spirit of aggression and revenge, often bordering on the pathological. The ‘reds’, they believed, were an inhuman mass, like a pack of rats, a poisonous flood pouring over Germany, requiring measures of extreme violence if it was to be held in check.’[14]

The ‘stab-in-the-back’ myth refers to the idea – an article of faith in German right-wing circles – that the German army had not been beaten on the battlefield, but that an unworthy peace was accepted by the (socialist and sometimes Jewish) politicians who were leading Germany in 1919.[15] Warlimont’s own Freikorps, led by General Georg Maercker, was no different from the other Freikorps, apart from the fact that Maercker was the main spokesman for the anti-Semitic faction in Stahlhelm, the largest German veterans-organization.[16] Anti-semitism was rife in the German military, already during the Empire, and the particular form of anti-Semitism (later used by the Nazis), in which ‘Jewish Bolshewism’ was the main enemy of Germany was already common in military circles right after the First World War.[17]

This then was the milieu the young Lieutenant Warlimont spent his time in. Many members of Freikorps became members of the new Reichswehr in the early 1920s and went on, like Warlimont, to become leading military figures during the Second World War. Their mentality, strongly anti-communist and anti-Semitic, with a deep belief in the untrustworthiness of democratic politics, would fit Nazi-Germany like a glove. Warlimont has not left any recorded memories of his Freikorps-years, apart from a brief reminiscence in an filmed interview in which he said that he and most of his fellow officers were more at home in Wilhelmine Germany than in any later period. The Weimar Republic was a ‘step back from the proud days of the Kaiser and Prussian rule.’[18]

According to nazi propaganda, the pictured Kommissar gave abundant information about positions of the Soviet army after he was captured in August 1941. Photo Picture Alliance/Fotoarchiv für Zeitgeschichte

The German Army after 1933

An argument that Warlimont and others have frequently put forward in their zeal to prove the ‘clean’ Wehrmacht myth is that the German armed forces were a politically neutral, professional army. The sacking of Von Blomberg, and Hitler’s assumption of the position as Germany’s supreme commander meant the army was politicized from that moment on – according to Warlimont. In his memoirs he calls the newly established OKW ‘das militärische Büro des Politikers Hitler.’[19]

Warlimont was not hopelessly naïve, but a consummate liar when he wrote this. The German armed forces had, by 1938, fully committed themselves to Hitler’s war aims, which were no secret. Already a couple of days after the National Socialist Machtübernahme on 30 January 1933 Hitler met with the leaders of the Wehrmacht. During the meeting Hitler presented his plans in which the armed forces would get the crucial task to conquer areas in the east to guarantee Germany’s Lebensraum. The inhabitants of these areas – Slav Untermenschen – would be disposed of in some way. Hitler’s speech is not very specific about the means, but the ends are clear: Germany will at some point start a war of conquest and will not be held back by any consideration about the people who live there. Nor will it feel itself bound by the Treaty of Versailles that limits the strength of the army. According to Evans, the atmosphere during the meeting was ‘intoxicating’.[20] The message was received with enthusiasm, and many of the senior officers concluded that National Socialism would be good for Germany. A totalitarian state, without any opposition from the left could only be good for the armed forces.[21] After this meeting there has never been serious opposition against Hitler’s plans.[22] Warlimont was too junior to be present at that meeting, but in the years following the meeting, he must have noticed that the Wehrmacht was preparing for war.

The OKW

As soon as Warlimont was apprehended by the allies to be tried at Nuremberg he tried to put as much distance between himself and the OKW. Together with other German Generals in similar positions he wrote a memo on the inner workings of the OKW, which they presented to General William Donovan of the Office of Strategic Services (the forerunner of the CIA). In a letter to Donovan Warlimont made his position clear and stated that he should not be considered part of the OKW: ‘Wherever reference is had (sic!) in the statement to the OKW only the highest commanding officers who were the immediate collaborators of Hitler [meaning Keitel and Jodl, JH] are intended to be referred to, and not the rank and file in the offices and departments [my italics, JH]. They were merely executing orders which they received. They did not advise. (…) I belonged to them. As Assistant Chief of Staff of the Operations Department I had no independent executive powers.’[23]

This is an absurdity if ever there was one. A general officer, employed full time by the OKW, chief of one of the main staff elements, claims that he was not to be considered part of the OKW. Only the two main chiefs, Keitel and Jodl, were the ‘real’ OKW. The allied military authorities were luckily not so naïve and kept Warlimont on the list of defendants of the OKW trial that was held in Nuremberg from November 1947 until October 1948.[24]

In his memoir Warlimont openly deplored the politicization of the OKW after the demise of Blomberg. But his words are disingenuous at best: Warlimont himself designed the top structure of the Wehrmacht supreme command, with the express goal to push general officers critical of Hitler to the margins: ‘It was after this affair that Walter Warlimont (…) altered the structure of the armed forces by creating the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht. Effectively superseding the War Ministry and promoting generals less critical of Hitler’s rule, the OKW made military decisions more directly subordinate to the Führer,’ historian Pierpaolo Barbieri has written.[25]

So, Warlimont had been shedding crocodile tears when he deplored Hitler’s increased powers. That Warlimont was one of the central functionaries of the OKW is also clear from his involvement in a number of activities of the OKW related to the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Barbarossa

The war with the Soviet Union was not just any war: it was the ideological war Hitler had prepared for all his political life.[26] It was to wipe out the ‘Slav Untermenschen’ in the east, create Lebensraum for German expansion, and terminate the Jewish-Communist USSR. No German officer (or German citizen for that matter) could profess innocence of these goals. Hitler never made a secret of them and he informed the army leadership of these goals right after he took power. Of course, Warlimont was a junior officer who was not present at the meeting in 1933. But he was present at a meeting where Hitler would be much more specific about his war in the east.

On 30 March 1941 the Führer received some hundred officers in the Reichskanzlei to inform them about the coming war in the east. Warlimont was present, although he had been informed of the upcoming invasion much earlier. Hitler told his Generals that the upcoming war was not just aimed at the destruction of the enemy’s military. The goal was to completely annihilate the enemy, militarily, socially and culturally (Vernichtungskampf). What should be left was open space for German expansion and some people who could execute forced labour in camps. Communists, Jews and those who could not be productive should be deported or terminated. The Generals should have no qualms, there was to be no soldierly comradeship (Ritterlichkeit) with the enemy.[27] Warlimont mentions this meeting in his memoir, and even explains the criminal orders that emanated from it, but pretends to be an onlooker, as if his OKW was not at all responsible for the criminal orders that made this Vernichtungskampf possible. In his memoir he even professes surprise that the officers present did not protest the orders at all.[28]

In his memoir Warlimont openly deplored the politicization of the OKW and described himself as on onlooker despite of his high rank

The criminal orders

To ensure that the Wehrmacht understood and executed the war in the east with the right attitude two orders for the invasion forces were prepared at the OKW. One was the so-called Kommissarbefehl, the order to kill political officers of the Red Army on the spot rather than make them prisoners of war, and thus deny them the normal protections they were entitled to under the Geneva Conventions. Warlimont explained that, according to Hitler, the Red Army political officers were guilty of ‘unmenschliche Scheusslichkeiten,’[29] especially committed by the Red Army’s invasion of East Poland in 1939.

The other order was the Barbarossabefehl, an order and a series of more detailed implementing orders. This turned the whole area of operations of Barbarossa into a free killing zone for the Wehrmacht. Literally everyone who did not comply with orders or wishes of the Wehrmacht could be treated with the ‘schärfste Mittel’ without the need to go to a military court either before or after the action. Soldiers of the Wehrmacht were permitted to kill anyone at will, on their own initiative, without any need to explain themselves.

And kill they did. Committing atrocities was not the exclusive domain of the SS or the Einsatzgruppen. The Wehrmacht assisted in all the atrocities on the eastern front. It hunted partisans, killed locals, women and children included, and killed Jews. That this has happened is not questioned anymore – the evidence is overwhelming,[30] but why it happened is still debated. Having orders that lifted the restrains on unlawful behaviour on the battlefield is likely a part of the explanation. The same troops that committed terrible atrocities on the eastern front were relatively law-abiding on other fronts, where orders like the Kommissar- and Barbarossabefehl were not part of the standing orders of the Wehrmacht.[31]

Warlimont tried several lines of defence after the war to evade his responsibility. The first one was not to consider himself a member of the organization that created those orders. A second line of defence was this: ‘Dass die ‘Einsatzgruppen der SD’ unter dem Deckmantel dieser Vereinbarungen alsbald nach Feldzugsbeginn auf geheime Anweising Hitlers an Himmler den planmässigen Massenmord an den Juden in den rückwärtigen Gebieten des Osten afnehmen würden, konnte von keinen der an den Gesprächen und Befehlen beteiligten Officiere nur im geringsten vermutet werden.’[32]

The original draftees were, according to Warlimont, at the time of creating the orders not aware what Einsatzgruppen were going to do. That is hard to believe too. Hitler had been quite clear about what he wanted in the East. In his general political program he did not mince words about the Soviet Union, communists and Jews. The Wehrmacht was ordered to support the Einsatzgruppen and while Nazi-Germany had ample synonyms to hide the truth, few people can have doubted what these Einsatzgruppen were for. It is true that there were no strict procedures for killings and for the precise kind of support the Wehrmacht was supposed to give the Einsatzgruppen. Since no one could predict what the actual circumstances were going to be, detailed planning was not carried out. The process of mass murder still had to be invented. Historian Waitman Wade Beorn, in his gruesome book on the Holocaust in Belarus, details how the Jews of Kripki, a small town, were murdered. SD Einsatzgruppen and the 354th Infantry Regiment of the Wehrmacht worked together: ‘The 354th Infantry Regiment improvised in its first encounter with murder; that is, the leadership operated without a set procedure. Beyond vague guidelines mandating logistical support, these men had no agreed-upon procedures for supporting an Einsatzgruppen killing. Yet, even in this early stage [of the war, JH] the Wehrmacht involved itself in all aspects of killing and had a surprising number of interactions with the Jewish population itself.’[33]

Beorn calls this one of the ‘many small Holocausts that took place in the East before the industrialized mass murder of the extermination centres.’[34] So this happened over and over on the eastern front. The fact that there were no set procedures gave Warlimont cum suis a little bit of wriggle room to argue that these were local initiatives or excesses. But the commander’s intent was clear, and that was why the Wehrmacht assisted in these killings without demur. The OKW knew what the Einsatzgruppen and SS were for, and knew what supporting them meant in practice: supporting mass murder. They had already been active during the Polish campaign in 1939. Wehrmacht personnel witnessed their activities, like the massacre at Przemysl, a three day, extremely bloody campaign to kill all the Jews in the city.[35] It was also during the Polish campaign that, according to historian Roger Moorhouse, the ‘German army’s slide into barbarism’ began.[36] Wehrmacht units needed little prompting to kill civilians and Polish prisoners of war. With the brutal Polish campaign in mind the Kommissarbefehl and the Barbarossa order and many of the other implementing orders during Barbarossa seem more like arrangements to improve the organization of brutality that had mostly been left to the initiative of local commanders in Poland, and to make sure that restrictions army commanders might feel to act ruthlessly were lifted. That the killing was more effective in Russia than in Poland, and that it was virtually absent in the western campaign in 1940, says a lot about the way the Wehrmacht could be steered into violence by its highest command. The violence was not senseless, it was planned, organized and controlled, and contained in orders created by the OKW.

At Nuremberg Warlimont was sentenced to life imprisonment for his collaboration in the creation of the Kommissarbefehl, but released in 1954. Photo US National Archives NextGen Catalog

Nuremberg

From November 1947 until October 1948 Warlimont and fellow officers of the OKW were tried at Nuremberg. Warlimont’s main goal was to explain to the judges that in spite of his position as the right-hand man of Jodl, who had already been sentenced to death and hung in October 1946, he bore no responsibility for any of the orders and policies of the OKW, along the lines shown above. Warlimont was not successful. The court sentenced him to life imprisonment for his collaboration in the creation of the criminal orders. The sentence was later reduced to 20 years, and he was released in 1954.

The Court was not impressed by Warlimont’s attempts to distance himself from Keitel and Jodl and judged that he and his fellow OKW staff officers could not evade criminal responsibility for executing orders they knew to be criminal: ‘It over-taxes the credulity of this Tribunal to believe that Hitler or Keitel or Jodl, or all three of these dead men, in addition to their many activities as to both military matters and matters of state, were responsible for the details of so many orders, words spoken in conferences, and even speeches which were made. We are aware that many of the evil and inhumane acts of the last war may have originated in the minds of these men. But it is equally true that the evil they originated and sponsored did not spread to the far flung troops of the Wehrmacht of itself. Staff officers were indispensable to that end and cannot escape criminal responsibility for their essential contribution to the final execution of such orders on the plea that they were complying with the orders of a superior who was more criminal.’[37]

Conclusion

Warlimont’s post-war life was dedicated to protecting his own legacy and that of the Wehrmacht. With lies, half-lies, omissions and distortions of the truth he created his myth of innocence. We know very little about the private man Warlimont, so whether he believed his own myths or whether he knew they were a survival mechanism to regain decency after the war is not known. We will unfortunately never know what was behind the myth.

The myth was a post-war invention. During the Hitler years Warlimont participated in Hitler’s crimes without much qualms. As a right-wing officer, rooted in Wilhelmine Germany, he likely shared most or all of the prejudices of the Nazi’s. And if he didn’t share them, they were in any case not reasons to remove himself from Hitler’s circle or from the Wehrmacht altogether. He remained a faithful servant in a criminal organization until he was pensioned off in late 1944 with physical problems that were a consequence of the bomb attack on the Führer on July 20 1944. He was in the room with Hitler when the bomb exploded and he suffered lasting effects of the explosion.

It is important to reiterate the core of Warlimont’s claim of innocence. The term he constantly comes back to is ‘professional’. His narrative is that in Nazi-Germany there existed professional soldiers and racist criminals. The latter were not part of the Wehrmacht but of the SS. The Wehrmacht simply carried out the profession of warfare. The problem is that this simple distinction between neutral, professional warfare and atrocities is impossible to make. The Wehrmacht was an integral part of the apparatus that carried out Hitler’s war goals, which included colonizing eastern territory, enslaving and murdering the people who lived there, and getting rid of the Jewish population in Europe. Even if the Wehrmacht had never as much as touched a civilian or a Jew, it would still be complicit in those goals. The narrative Warlimont wants to believe is that there were two wars going on, one with strictly military goals and one with political goals and that somehow activities can be separated in ‘neutral military’ and ‘criminal.’ But it is impossible to separate the invasion of the Soviet Union – the main goal of Hitler’s war – from the aim with which that invasion took place.

After his conviction at Nuremberg Warlimont was lucky that everybody – Germany itself, but also the United States and Great Britain – wanted to forget the Nazi-years. The Cold War was a golden era for myths of innocence. Everybody wanted to believe the ‘clean’ Wehrmacht myth because the new Bundeswehr was needed for the defence of Europe. Part of the acceptance of this myth was the early release of people like Warlimont. Very few of Warlimont’s colleagues completed their prison terms.[38] It is, after all, hard to claim that the Wehrmacht was innocent if most of its former generals were behind bars for various war crimes. But Warlimont’s luck can, in the end, not erase his complicity.

[1] Jonathan Bach and Benjamin Nienass, ‘Innocence and the Politics of Memory’, German Politics and Society, Issue 135 Vol. 39, No. 1 (Spring 2021) 1-14.

[2] Letter from Warlimont to William Donovan, November 19, 1945. Cornell University, William Donovan Nuremberg Trials Collection, https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/nur00632.

[3] He arrived as an Oberst (Colonel), was promoted to Generalmajor (Major General) in 1940, and to General der Artillerie (Lieutenant General) in 1944.

[4] Walter Warlimont, Im Hauptquartier der deutschen Wehrmacht 1939-1945 (Band 1) (Augsburg, Weltbild Verlag, 1990) 29.

[5] Ibid, 28.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid, 187.

[8] International Military Tribunal ‘High Command Case: Walter Warlimont Testimony’ (1948). Nuremberg

Transcripts. 15. https://commons.und.edu/nuremburg-transcripts/15.

[9] The name Warlimont is more common in Belgium than in any other European country, see: https://nl.geneanet.org/genealogie/warlimont/WARLIMONT.

[10] International Military Tribunal ‘High Command Case: Walter Warlimont Testimony’.

[11] The most famous example being Heinrich Himmler. He was still a Fähnrich (officer candidate) in a German regiment when the First World War ended, and for him, and many of what is called the ‘war youth generation’ the Freikorps was a way to redeem themselves for missing the opportunity to fight for Germany in the war. See: Peter Longerich, Heinrich Himmler (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012) 23-28.

[12] The leaders of the communist revolutions in Germany.

[13] Richard Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich. How the Nazis Destroyed Democracy and Seized Power in Germany (London, Penguin Books, 2004) 74.

[14] Ibid, 75.

[15] General Erich Ludendorff, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg’s Quartermaster General on the western front, was in fact himself convinced of the impossibility to wage war on the western front any longer on 29 October 1918, and informed the Kaiser as such. Later Ludendorff changed his mind and became the first proponent of the stab-in-the-back myth. See: Manfred Nebelin, Ludendorff. Diktator im Ersten Weltkrieg (Munich, Siedler Verlag, 2011).

[16] Wolfram Wette, The Wehrmacht. History, Myth, Reality (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2006).

[17] Ibid, 43.

[18] Marcel Ophuls, The Memory of Justice (documentary, Paramount Pictures, 1976).

[19] Warlimont, Im Hauptquartier der deutschen Wehrmacht 1939-1945, 29.

20 Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich, 316-317.

[21] Stephen Fritz, The First Soldier. Hitler as a Military Leader (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2018) 48-49.

[22] The later opposition of officers against Hitler was, in my view, mostly directed against the Führer’s management of the war than against his plans. As long as Hitler was winning, his officers supported him.

[23] Letter from Warlimont to William Donovan.

[24] The trial is also known as the High Command Trial or sometimes the 13 Generals Trial. Formally it was called The United States of America vs. Wilhelm von Leeb, et al.

[25] Pierpaolo Barbieri, Hitler’s Shadow Empire. Nazi Economics and the Spanish Civil War (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2015).

[26] Western Europeans are understandably more interested in the war in the West against France and England, but these were technically preparatory operations to make the invasion of the Soviet Union possible.

[27] Fritz, The First Soldier, 123-127; Jürgen Förster and Evan Mawdsley, ‘Hitler and Stalin in Perspective. Secret Speeches on the Eve of Barbarossa,’ War in History, Vol. 11, No. 1 (January 2004) 61-103.

[28] Warlimont, Im Hauptquartier der deutschen Wehrmacht 1939-1945, 177.

[29] Ibid.

[30] E.g. Wolfram Wette, The Wehrmacht. History, Myth, Reality (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2006); Waitman Wade Beorn, Marching into Darkness. The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust in Belarus (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2014).

[31] One exception is the Kommandobefehl, the order to kill members of allied commando units, even when they were in uniform, and thus protected by the Geneva Conventions. This was explicitly a Wehrmacht order aiming at the front in the West, emanating from the OKW. Although its genesis was different, it was more a reaction to the many allied commando raids on the Atlantic coast than an ideological order as the Kommissarbefehl; it was a criminal order nonetheless. See: Andreas Jasper, ‘Radikalisierung im Westen? Zum Verhältnis von Ideologie und Handlungssituation an der Invasionsfront,’ Militärgeschichtliche Zeitschrift, Volume 66 No. 2 (2014).

[32] Warlimont, Im Hauptquartier der deutschen Wehrmacht 1939-1945, 175.

[33] Beorn, Marching into Darkness,65.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Roger Moorhouse, First to Fight. The Polish War 1939 (London, The Bodley Head, 2019) 208-209.

[36] Ibid, 137.

[37] US Military Tribunal Nuremberg, Judgment of 27 October 1948, in Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals, Vol. IX, 514.

[38] Donald Bloxham, ‘Punishing German Soldiers during the Cold War. The Case of Erich von Manstein,’ Patterns of Prejudice, Vol. 33, No. 4 (1999) 25-45.