On March 22, 1999, NATO authorised the start of Operation Allied Force and conducted air strikes against targets in the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia for 78 days. The Federal Republic capitulated on June 10, 1999. Two days later, the first NATO troops, or KFOR-I, entered Kosovo under the umbrella of the NATO-led Operation Joint Guardian. In 2008, Kosovo issued a unilateral declaration of independence, aggravating political tensions in the region. Over the past three years numerous protests and attacks have occurred in the North of Kosovo, often requiring KFOR to intervene. All these incidents point to an enmity that still exists between Serbia and its former province and they stress the importance of KFOR as much-needed security presence on the ground even after sixteen years.

Anika Snel MSc and Lisa Ziekenoppasser LLM BSc*

On August 27 and 28, 2014, two shooting incidents took place between illegal wood loggers from the Republic of Kosovo[1] and members of the Serbian Gendarmerie on the Serbian side of the Merdare crossing point. The incident resulted in the death of both a Serbian Gendarmerie Officer and a Kosovar Albanian.[2] Following the killings, the Chief of Staff of the Serbian Armed Forces and the Commander of the Multinational Kosovo Forces (COMKFOR) agreed to strengthen joint patrols at the Serbia-Kosovo border. In a press release, the Kosovo Force (KFOR) pledged to continue contributing to the normalisation of the situation in the border area, in close cooperation with the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX) and the Kosovo Police (KP).[3] Both the Serbian Minister of the Interior and the Serbian Prime Minister accused the wood cutters of acts of terrorism. Meanwhile a number of Kosovo politicians counter-argued that Serbia often presents Kosovo as a threat to the stability of the Balkan region.[4] In the same week, an anonymous NATO official was quick to respond to questions posed by the Serbian state news agency Tanjug, that the alliance had no plans to reduce its number of troops in Kosovo: ‘The troops in Kosovo have a clear mandate from the UN Security Council, and both the Albanians and Serbs want them to stay.’[5] The remark was confirmed by the Serbian Minister of Foreign Affairs who stressed during the 69th United Nations (UN) General Assembly session, at the end of September 2014, that the presence of international forces is a key for stability and safety in ‘Kosovo and Metohija’.[6] The incident with the illegal wood loggers is just one example of recent hostility at the Kosovo-Serbia border. Over the past three years, especially in 2011 and 2012, numerous protests and attacks have occurred in the North, often requiring KFOR to intervene. All these incidents point to an enmity that still exists between Serbia and its former province after Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence in 2008.

Operating within a sensitive political arena: a member of KFOR takes his turn cutting up confiscated weapons in Kosovo. Photo UN, R. Sullivan

The violence and fragile security situation in (northern) Kosovo have proven to be a continuous challenge to the goals of the international community: to help retain a safe and secure environment for all people in Kosovo, and to deter renewed hostility between the Kosovar Serbs and Kosovar Albanian people. Precisely these goals constitute the main tasks of KFOR, the longest-lasting mission in the history of NATO. Although the mission has lasted for sixteen years now, not many people are aware that it still exists, and are even less aware of the fact that the Netherlands still contributes military personnel.[7] This raises the following question: why is KFOR still of significant importance after sixteen years? The aforementioned incidents emphasize the continued need for KFOR to act as a security provider. Yet considering the mission has been in place for so long it would be too simplistic to argue that KFOR is still needed just because the national security situation would require so. Such a statement does not reflect the complex reality wherein the mission operates. This article analyses the political and military developments of the last sixteen years that have influenced the position and tasks of KFOR as a military stabilisation force in Kosovo. The first paragraph narrates the establishment of KFOR and its initial mandate and tasks. The second paragraph consists of two parts. The first part describes Kosovo’s declaration of independence, followed by a discussion of the consequences of this development for the original tasks of KFOR. The third main paragraph expounds the situation in the northern part of Kosovo, as even after sixteen years KFOR is the only reliable security guarantee within this fragile area. The fourth paragraph analyses the contemporary political bilateral Serbia-Kosovo relations and the position of KFOR within this sensitive political arena. The main question of this article will be revisited in the concluding section.

KFOR’s mandate and tasks

On March 22, 1999, NATO authorised the start of Operation Allied Force and conducted air strikes against targets in the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia for 78 days.[8] The Federal Republic capitulated on June 10, 1999. Two days later, the first NATO troops, or KFOR-I, entered Kosovo under the umbrella of the NATO-led Operation Joint Guardian. On June 10, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1244. This resolution decides ‘under United Nations auspices, on the deployment in Kosovo of international civil and security presences’,[9] leading to the creation of the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). In addition, Resolution 1244 authorises ‘The Secretary-General, with the assistance of relevant international organisations, to establish an international civil presence in Kosovo in order to provide an interim administration for Kosovo under which the people of Kosovo can enjoy substantial autonomy within the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia [...].’[10]

While the resolution does provide for an interim international administration under the auspices of the UN, it does not determine the legal status of Kosovo. As Article 10 of Resolution 1244 states, Kosovo can enjoy substantial autonomy, but within the territorial integrity of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In addition, Resolution 1244 allows for an ‘open-ended period of time.’[11] Consequently, there is no end date to the mandate. UNMIK’s mandate originally consisted of four pillars: (1) Civil Administration, (2) Humanitarian Assistance, (3) Democratisation and (4) Institution-Building, Reconstruction and Economic Development. The first pillar was the responsibility of UNMIK. The original second pillar aimed at the successful return of refugees to Kosovo but was replaced by the Police and Justice Pillar in May 2001.[12] The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) took charge of the third pillar and the European Union (EU) took responsibility for the pillar of construction and economic development.

Meanwhile on June 20, 1999 Operation Allied Force was concluded. At that time, all Serbian forces and police had been withdrawn from Kosovo, as agreed upon in the Military Technical Agreement (also known as the Kumanovo Agreement) between NATO and the Government of the Former Republic of Yugoslavia.[13] In addition to the tasks of UNMIK, NATO was responsible for maintaining military stability in Kosovo. Since its initiation, the NATO mission derived its mandate from Resolution 1244 and later from the Military Technical Agreement. The mission operates under Chapter VII of the UN Charter as a peacekeeping operation.[14] The original mandate of KFOR was to help maintain a safe and secure environment and freedom of movement for all people in Kosovo, to deter renewed hostility and threats against Kosovo by Yugoslav and Serb forces, to disarm the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and to support the international effort to bring stability to Kosovo.[15] To implement this mandate, KFOR took up a wide scope of initial tasks. These tasks included (a) offering assistance for a safe and free return of all refugees and displaced persons; (b) providing security and public order, with a special focus on the border areas; (c) support ammunition, weapons and explosives control programmes; (d) perform medical assistance; (e) support infrastructural reconstruction and de-mining; (f) providing protection of patrimonial sites; (g) and finally supporting the establishment of civilian institutions.[16] This wide range of tasks exemplifies the complexity and extensiveness of the mandate.

The Decani Monastery is the only designated site in Kosovo that currently remains under fixed KFOR protection. Photo author’s collection

In its heyday, KFOR was composed of approximately 50,000 troops. The first reduction of troops occurred during 2002 and by the end of 2003, due to an improved security environment, KFOR reduced its troops to 17,500 personnel. As the security situation continued to improve during the years, in June 2009 the North Atlantic Council (NAC) decided to gradually redefine KFOR’s presence to a ‘deterrent presence’.[17] By February 2011, KFOR had successfully reduced its troops to an approximate number of 5,000.[18] Currently, two Multinational Battle Groups (MNBG) remain in place.[19] The headquarters of KFOR is located at Camp Film City in the capital of Kosovo, Pristina. The mission is under command of COMKFOR who reports to the Commander of Joint Force Command Naples (COM JFCN). Since September 2014, KFOR-XIX has the continued support of 31 nations,[20] still within the original mandate as agreed upon sixteen years ago.

2008: A year of change

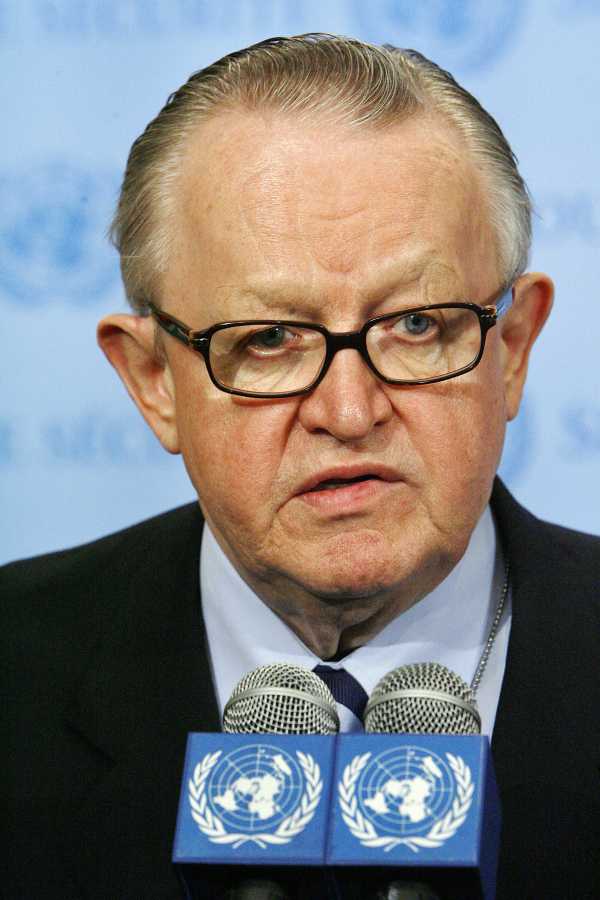

2008 was a crucial year for the future of Kosovo, the Balkan region and the international presence in Kosovo. It was the year when Kosovo, on February 17, unilaterally declared independence.[21] The road to independence was a highly controversial one. Resolution 1244 did not clarify the legal status of the former province of Serbia. Therefore, in 2005, the UN initiated a process to settle the status of Kosovo. As a result, the UN Secretary-General, Mr. Ban Ki-Moon, appointed the former president of Finland and former mediator in the 1999 conflict, Mr. Martti Ahtisaari in November 2005 as Special Envoy to lead the political process to determine the future status of Kosovo. In 2006 he facilitated several negotiations between the local Kosovar government and the government of Serbia regarding the settlement of Kosovo’s status. Ahtisaari submitted a draft settlement proposal on February 2, 2007.[22] Shortly after, the negotiations to finalise the settlement between both parties started. The negotiations ended without result. On March 23, Ahtisaari presented to the UN Security Council his final proposal, the Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement, also called the ‘Ahtisaari Plan’. His proposal contains the idea of ‘independence, under international supervision for an initial period.’[23] The international community proved divided, since the plan proposed an independent Kosovo. In addition, the plan was meant to replace Resolution 1244. Ahtisaari’s final settlement was accepted by the local government in Pristina while it was strongly opposed by Serbia and its ally Russia. Russia rejected a UN Security Council resolution based on the ‘Ahtisaari Plan’ and implied it would veto such a Resolution in the Security Council.[24] Kosovo’s status was left unresolved, no agreement was reached between Serbia and the local government of Kosovo and Resolution 1244 remained in place. Not long after, in February 2008, Kosovo unilaterally declared independence.

The Assembly of the newly formed Republic of Kosovo committed itself to the full implementation of the proposal of Special UN Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, a plan strongly opposed by Serbia and its ally Russia. Photo UN, M. Castro

The Assembly of the newly formed Republic of Kosovo committed itself to the full implementation of the ‘Ahtisaari Plan’. The provisions of the proposal are enshrined in the Constitution and approved by the Assembly on April 9, 2008 and entered into force on June 15, 2008.[25] Serbia, not recognising the independence of Kosovo, requested an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice on the question if the unilateral declaration of independence by the provisional institutions of the self-government of Kosovo was in accordance with international law. On July 22, 2010, the Court of Justice ruled its advisory opinion stating ‘that the declaration of independence of Kosovo adopted on 17 February 2008 did not violate international law’.[26] Despite the ruling of the International Court, Serbia still does not recognise Kosovo as an independent state.

Shortly after independence, the international situation on the ground changed significantly when the largest civilian EU-led mission ever in history, EULEX, became effective. With the start of the mobilisation of EULEX in February 2008, the international presence in Kosovo not only became more complex, but also more delicate. As Resolution 1244 was still operative, all legislative, executive and judicial issues needed authorisation of the UN Secretary-General. However, Mr. Ban agreed to the transfer of all police and justice matters to the EU, with the stipulation that these issues remained under the rulings of Resolution 1244. As such, the supervision of the Kosovo Police, Justice and Civil Administration were transferred from UNMIK to the EU, with the EU being accountable to a Special Representative of the UN. Within the UN Security Council a discussion emerged whether Resolution 1244 did indeed authorise EULEX. Most EU member states and the United States (US) opined that EULEX was authorised by virtue of Resolution 1244. However, Russia and Serbia do not recognise the mission and claim that it does not have its foundation in Resolution 1244. Moreover, Russia and Serbia concluded that EULEX is not legitimate, referring to what they see as the illegal unilateral declaration of independence of Kosovo.[27] To date, this reasoning is still supported by both states.

Adjustments of KFOR’s original tasks

Both the declaration of independence as well as the start of EULEX affected the initial tasks of KFOR. Three main adjustments of KFOR’s role and mandate were carried out. After declaring independence, the Kosovo government signed a law to establish a Ministry for a Kosovo Security Force (KSF).[28] This development established Kosovo’s security ownership. Following the constitution and the institutionalising of the Ministry for the KSF at June 12, 2008, NATO agreed to assist with the dismantling of the Kosovo Protection Corps (KPC).[29] Secondly, KFOR was going to assist and supervise the formation of a multi-ethnic KSF. The KSF is a light-armed force, without any heavy weapons or offensive air capabilities.[30] The KSF consists of 2,500 active army soldiers (mainly light infantry) and 800 reserves.[31] In order to continue supporting the KSF, in July 2013 the NAC established the NATO Liaison and Advisory Team (NLAT). The NLAT is distinct from KFOR and placed directly under NATO Headquarters in Brussels.[32] KFOR is tasked to support the NLAT.[33] The NLAT consists of approximately 35 military and civilian personnel and is tasked with providing high-level advice to the Ministry of KSF on strategic defence reviews and staff capacity-building and training.[34] In addition, the NLAT assists in establishing a civilian-led organisation that exercises control over the KSF. Thirdly, based on the aforementioned troop reduction in 2011, KFOR’s role in security provision has been revised to the role of third responder to security threats, behind the KP (first responder) and EULEX (second responder).[35]

An explosive ordnance disposal technician (U.S. Army) assists a Kosovo Security Forces EOD soldier with properly setting up for an electric demolition during a training event, 2013. Photo US Army, S. Parks

Within the government structure the KSF comes under the Ministry for the KSF. This ministry is accountable to the Kosovo Assembly’s Security Committee. Due to developments within the security sector of Kosovo after it claimed its independence, the government in April 2012 announced the start of a new study programme regarding a Security Sector Reform (SSR).[36] In March 2014, the SSR presented its recommendations to be carried out by the government over the next five years. The recommendations cover a number of aspects and listed requirements. Among other things the report recommends the development of a new National Security Strategy and the improvement of Kosovo’s emergency response capabilities. However, the most important recommendations – as interpreted by the Kosovo government – are the renaming of the Ministry of the Kosovo Security Force into the Ministry of Defence and the production of a National Defence Strategy (December 2014).[37] These developments were and still are motivated by Kosovo’s main desire to establish a National Army for Kosovo. Due to a political deadlock after national elections in June 2014, delaying the formation of a government for almost six months until 9 December 2014, the approval of the National Defence Strategy has been postponed.[38] However, the newly formed government has pledged itself again to the transformation of the KSF into a National Army in the year 2015.[39]

KFOR and northern Kosovo: from fragile tolerance to wary acceptance

After its independence the security situation in Kosovo improved, as confirmed by the reduction of NATO troops since 2009. However, this improvement has not spread to the northern part of Kosovo where the majority of Kosovar Serbs reside. As a matter of fact, compared to the other parts of Kosovo, the northern area is the main region where KFOR’s original mandate – to maintain a safe and secure environment and freedom of movement for all people in Kosovo and to deter renewed hostilities – has effectively remained unchanged. From its initiation it was clear that the EU mission would not be able to decrease Serbia’s influence in northern Kosovo. The first three months after independence saw Kosovar Serbs in the North (often called ‘hard-liners’ and civilian-clothed security agents) attempting to abuse the security situation aiming at a de facto partition of the northern region. They attacked administration facilities, threatened EU staff that forced them to evacuate North-Mitrovica and occupied the court premises in North-Mitrovica.[40] Order was restored by KFOR’s intervention. During the court eviction, KFOR and UNMIK troops were met with automatic weapons fire and grenades, which resulted in lethal casualties. Nevertheless, the international forces prevailed and the robust performance of KFOR largely surprised the Kosovar Serbs who were the driving force behind the occupation. This has led to an arduous tolerance of KFOR’s continuous presence in the North. Still, while the attempts to force a de facto partition of northern Kosovo had failed, both Kosovar Serbian leaders in the North and Serbia continued to treat the northern part as a separate entity of the rest of Kosovo. Furthermore, Serbia continues to exercise a significant influence over the North through parallel security actors, including police forces and a so-called ‘civil protection corps’, obfuscating the security situation.[41]

Nevertheless, the Serb population in the North of Kosovo has tolerated KFOR as security provider over the past years. Their relationship has sometimes been fragile and at other times leaning towards actual reluctant acceptance. When in August 2009 a first announcement was made to downsize KFOR and move towards a deterrent force, Serbia protested, arguing that ‘KFOR was the only force that Serbs in Kosovo could trust.’[42] Notwithstanding such remarks, KFOR continuously has been forced to deal with many types of violence conducted against the mission by the Serbian community living in the North. The violence often stemmed from the threat KFOR’s activities posed to organised crime. At the same time, political decisions by the Kosovar authorities that were seen as threats to the self-proclaimed separate status of northern Kosovo often caused a vehement reaction among the Kosovar Serbian population. In turn, such outbursts sometimes developed into an actual threat to the security situation in the North. In 2011 both a decision by the Kosovo government to deploy Kosovar customs officials to the administrative border crossing points with Serbia and a failed attempt by the Kosovo special police to retake control over two border crossing points in the North, led to the setting up of roadblocks by the Serbian hard-line population. KFOR was forced to intervene to ensure freedom of movement for the international community and to guarantee a stable and secure environment. Attempts to remove the barricades were met with violence, even resulting in KFOR personnel being injured.[43]

In 2012 similar incidents at the border crossing under the control of KFOR continued to occur.[44] During the first months of 2013, KFOR again was required to dismantle barricades set up to block the roads to the border crossings.[45] In actual practice, the NATO-led mission has acted as the first or second security responder to similar threats to the freedom of movement and the security environment in the North, even though the mission is supposed to act as a third responder, after the KP and EULEX respectively. Nevertheless, determined action by KFOR against these physical attempts to undermine original agreements on the status of North Kosovo has seemingly been accepted by the Kosovar Serbian population. This acceptance is partly due to KFOR’s other responsibility: the protection of the Serbian-Orthodox cultural heritage sites south of the Ibar River. Also, even though the pinpointed violence committed against KFOR has regularly been instigated by NATO’s response to criminal activities, the Kosovar Serbian population has never staged violent protests against KFOR itself. Instead, protests have been triggered by the enforcement of political decisions of both Serbia and Kosovo which, in the view of part of the Kosovar Serbian population, threatened their legal presence in North Kosovo. Lastly, while Serbia and the Kosovar Serbian population in the North still consider both EULEX and the KSF an unacceptable power, the presence of KFOR is legitimized.

Brussels Agreement: reaffirmation of the role of KFOR

Besides political developments at the state level which influence the tasks and presence of KFOR, there are also significant developments between Serbia and Kosovo at a regional level. In 2011, Kosovo and Serbia started a political dialogue under the auspices of the European External Action Service (EEAS), aimed at normalising their mutual relationship. For both states a future of European integration was at stake: for Serbia a successful dialogue was a precondition for the start of EU accession negotiations, while for Kosovo a successful agreement would lead to the opening of negotiations on an upcoming Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA).[46] This high level dialogue resulted in the ‘First Agreement of Principles Governing the Normalisation of Relations’, in short the Brussels Agreement, signed on April 19, 2013.[47] In the Agreement, both states committed themselves to 15 key points covering various fields, including the integration of the Serb majority in North Kosovo under the jurisdiction of Pristina, the establishment of an Association of Serbian Municipalities and integrated border management and security provision in northern Kosovo.

Internationally, the Brussels Agreement is considered an important step forward for regional peace and security.[48] Interestingly, while signing the Agreement, Belgrade specifically requested the continuing involvement and presence of KFOR in Kosovo. It seems KFOR is viewed as the only credible protection for Kosovar Serbs and the main security guarantor of the Brussels Agreement.[49] It can be argued that the regional security relationship between Kosovo and Serbia continues to rely on a NATO presence. This argument is reinforced by the continuing distrust of the Kosovar Serbian population towards the KSF and EULEX, and Serbia’s refusal to recognise the KSF. In the past and in the present, Serbian political leaders have even argued that the KSF provides a potential security risk to Serbia, the Kosovar Serbs and even to the Kumanovo Agreement.[50] As an independent state, one of the foremost interests of Kosovo is to protect its recently gained territorial integrity. The upgrading of the KSF to a capable army would present the next step in the consolidation of Kosovo’s statehood and it proves to be in Serbia’s interest to obstruct that. Despite KFOR training the KSF to prepare them for the transformation into a properly equipped army, Serbia does recognise KFOR as the main military actor in Kosovo and even cooperates with NATO troops along the border. KFOR has become part of a political controversy in a politically sensitive arena. In addition, Serbia’s request for security guarantees for the Serbian municipalities in the North of Kosovo, as stated in the Brussels Agreement, entails the commitment of KFOR in these areas for the foreseeable future. Moreover, both Kosovo and Serbia have demonstrated reluctance in the implementation of the Agreement.[51] Due to national elections in both Kosovo and Serbia, with a 6-month political impasse in Kosovo, the implementation of the Agreement, as well as the political dialogue, have practically been put on hold.[52]

Conclusion

This article analysed the reasons why KFOR is still of a significant importance after sixteen years, specifically focusing on the political-military developments after 2008. As Resolution 1244 remains in place, without an end date set for the mission, its primary duty continues to be the provision of a safe and secure environment, particularly in the North of Kosovo. Moreover, not all of the original tasks have been fully accomplished yet. This is demonstrated by the shooting incidents at the Merdare crossing point in August 2014 and the ongoing tensions in the North and the border area between Kosovo and Serbia. Of all the international security players active in Kosovo, KFOR is the main security provider accepted by the Kosovar Serbian population and Serbia itself, albeit hesitantly. This varying degree of acceptance has been largely based on changes in the force posture of KFOR, the additional tasks of assisting the KSF and the protection of Serbian-Orthodox cultural/religious heritage, as well as the consequences of political decisions of both Serbia and Kosovo at the highest governmental level. The regional security architecture between Kosovo and Serbia is based on the presence of KFOR. Consequently, KFOR has become a politicised mission in which political and military goals are mutually interlinked. From the perspective of Kosovo, despite the disagreement on its independence and territorial integrity, the presence of KFOR helps to mitigate existing security threats and the development of the ongoing SSR. For Serbia, KFOR is the only security guarantee for the Serbian population in Kosovo. Indirectly, they attempt to obstruct the next step in the consolidation of Kosovo’s statehood by influencing Kosovo’s security situation through refusing a fully pledged KSF force.

Within this politicised environment, the mission has to be commended on the progress made in the implementation of the additional tasks since 2008. The KPC has been dissolved and the KP has emerged and the KSF has made significant steps forward. A possible development that could influence or change the need for KFOR’s presence and tasks would be the installation of a Kosovo National Army. Should such a scenario be realized, which might happen in 2015, some or all of the tasks are likely to be handed over to a new defence force. If the mandate and tasks of the KSF change though, it is up to the NAC to reconsider the level of NATO’s involvement in Kosovo in time to come. However, a change in the mission and mandate of the KSF will not improve the tense relationship between Kosovo and Serbia nor will a change in the level of involvement of KFOR. As long as there is no formal, signed peace agreement between Serbia and Kosovo, the security situation, especially at the border zones and in North Kosovo, remains fragile. KFOR was, is, and will likely continue to be the only reliable international security force in Kosovo. After sixteen years the Serbia-Kosovo relations still dictate the necessity for KFOR as the main security presence on the ground. The current uncertainty surrounding the normalisation process in combination with KFOR’s role as the main security guarantor of the Brussels Agreement ensures that KFOR’s footprint on Kosovo’s fields will be visible for a long time to come.

* Anika Snel currently works as a political advisor at the Netherlands Embassy in Pristina, Kosovo. She has an academic background in governance and political science and has previous work experience with the Dutch non-governmental organisation SPARK in northern Kosovo. Lisa Ziekenoppasser recently completed a traineeship with the Netherlands Embassy in Pristina. She has an academic background in political sciences and international security and has previous work experience as an intern at the Netherlands Defence Academy (Breda) and Headquarters 1 (DEU/NLD) Corps (Münster, Germany). Lisa currently follows a traineeship at the Civil-Military Cooperation Centre of Excellence with the Netherlands Embassy in Pristina. The views represented in this article are the personal views of the authors.

[1] Hereinafter referred to as Kosovo.

[2] Division of Public Information, United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), ‘Gendarmerie member dies from wounds,’ ‘Serbian policemen killed on border with Kosovo’, Belgrade Media Report (28 August 2014). Retrieved from http://media.unmikonline.org.

[3] Press and Public Information Office (PPIO) European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX), ‘Comments on incidents’, Kosovo Media Monitor Draft 0830 Report (29 August 2014). Retrieved from http://newsmonitors.org.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid; Press and Public Information Office (PPIO), European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX), ‘NATO to stay in Kosovo’, Kosovo Media Monitor Draft 0830 Report (29 August 2014).

[6] ‘Kosovo and Metohija’ is the Serbian designation for Kosovo, as a province in the Republic of Serbia. See: Division of Public Information, United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), ‘International forces key for safety in Kosovo and Metohija’, Belgrade Media Report (26 September 2014).

[7] On March 23th, 1999 the Dutch government authorised the participation of military air support and maritime support during Operation Allied Force. The Netherlands also supported Operation Joint Guardian through KFOR-I and KFOR-II. Within KFOR-I and KFOR-II, over 2,000 Dutch military personnel contributed to the implementation of the mission mandate. The Netherlands did not contribute to the mission after KFOR-II, however, restarted with the deployment of troops to KFOR-X in October 2005. Annually, approximately ten Dutch military personnel are stationed at the KFOR headquarters in Pristina (Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie, ‘Operation Allied Force’, 2009).

[8] The legitimacy of the intervention is still widely debated among international law experts. The air strikes executed by NATO were vetoed by China and Russia in the Security Council stressing the violation of state sovereignty, the same argument used by Serbia. The North Atlantic Council authorised Operation Allied Force. NATO legitimated the intervention in light of the unfolding humanitarian catastrophe in Kosovo. This article will not go into this debate, as it would cover a separate article. However, it is important to realise the complexity and controversy of the intervention, as it still influences contemporary political developments in the region.

[9] UN Security Council, S/RES/1244 (10 June 1999).

[10] Ibid. Article 10.

[11] E. de Wet, ‘The governance of Kosovo: Security Council Resolution 1244 and the Establishment and functioning of EULEX’, The American Journal of International Law, 103, 1 (2009) p. 83.

[12] O. Dursun-Ozkanca, ‘Rebuilding Kosovo: Cooperation for Competition between the EU and NATO’, prepared for delivery at the 2009 EUSA Eleventh Biennial International Conference, Marriot Marina Del Rey, Los Angeles, CA, April 23-25 2009, p. 7.

[13] International Security Force (‘KFOR’) and the Governments of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Republic of Serbia, ‘Military Technical Agreement,’ Appendix A (9 June 1999).

[14] UN Security Council, S/RES/1244 Annex 2 (10 June 1999).

[15] NATO, ‘NATO’s role in Kosovo’ (2014). Retrieved from http://www.nato.int.

[16] There are eight unfixed properties with a Designated Special Status: The Gazimestan Monument, the Archangel site, Devic Monastry, Gracanica Monastery, Zociste Monastery, Budisavci Monastery, Gorioc Monastery and Pec Patriarchate. The Decani Monastery is the only designated site that currently remains under fixed KFOR protection (NATO, ‘NATO’s role in Kosovo’ (2014). Retrieved from http://www.nato.int); International Security Force (‘KFOR’) and the Governments of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Republic of Serbia, ‘Military Technical Agreement’ (9 June 1999); S/RES/1244 Article 11 a-k (10 June 1999).

[17] Deterrent Presence is a concept of operations whose main effort is based on small, regionally dispersed so-called liaison monitoring teams (LMTs). In addition, it launched the process of reducing forces and reorganising command structure. See Allied Joint Force Command Napels, ‘KFOR reaches ‘Gate 2’ through Deterrence Presence in Kosovo’ (2011). Retrieved from http://www.jfcnaples.nato.int; J. DeRosa, ‘Strategic Defense Review of the Republic of Kosovo’, GAP Policy Paper (2013) p. 16 footnote 6.

[18] NATO, ‘NATO’s role in Kosovo’ (2014).

[19] MNBG East is located at Camp Bondsteel near Ferizaj/Urosevac and mostly consists of U.S. troops. MNBG West is located in Peja/Pec at Camp Villagio Italia.

[20] Germany and the United States are the largest contributors to KFOR. However, in addition to the NATO member states, also KFOR non-NATO contributing nations support the mission. A KFOR non-NATO contributing nation ‘is a NATO operational partner that contributes forces/capabilities to KFOR – or supports it in other ways.’ NATO, ‘Key Facts and Figures’ (2014). Retrieved from http://www.nato.int.

[21] Since 2008, Kosovo has received 110 diplomatic recognitions as an independent state. There are still five European member states that do not recognise Kosovo’s independence: Spain, Slovakia, Cyprus, Romania and Greece.

[22] United Nations Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the Future Status Process for Kosovo, ‘Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari presents his proposal for the future status of Kosovo in Belgrade and Pristina’, UNOSEK/PR/16 (2 February 2007). Retrieved from http://www.unosek.org/unosek.

[23] UN Security Council, ‘Report of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General on Kosovo’s future status’, S2007/168, p. 2.

[24] BBC News, ‘Russia threatens veto over Kosovo’ (24 April 2007). Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk.

[25] The subsequent laws that followed the newly established constitution provided a security structure within the conditions of the ‘Ahtisaari Plan’. In general, although the ‘Ahtisaari Plan’ was rejected by Russia and Serbia, it is used by the international community and Kosovo as the basic policy framework for follow-up agreements and laws. (Assembly of the Republic of Kosovo, ‘Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo’ (15 June 2008).

[26] International Court of Justice, ‘Accordance with international law of the unilateral declaration of independence in respect of Kosovo’, Advisory Opinion (22 July 2010).

[27] O. Dursun-Ozkanca, ‘Rebuilding Kosovo: Cooperation for Competition between the EU and NATO’, prepared for the delivery at the 2009 EUSA Eleventh Biennial International Conference, Marriot Marina Del Rey, Los Angeles, CA, April 23-25 2009, p. 13; E.D. de Wet, ‘The governance of Kosovo: Security Council Resolution 1244 and the Establishment and Functioning of EULEX’, in: The American Journal of International Law (2009) (103-1) p. 83-96.

[28] Assembly of the Republic of Kosovo, ‘Law on the Ministry for Kosovo Security Forces’, Law No. 03/L-045 (13 March 2008).

[29] The KPC was conceived as a transitional post-conflict arrangement. Its mandate was to provide for disaster-response services, perform search and rescue and provide humanitarian assistance and contribute to reconstruction. The KPC was formally dissolved on June 14, 2009. NATO, ‘NATO’s role in Kosovo’ (2014).

[30] The mission of the KSF is ‘to conduct crisis response operations in Kosovo and abroad; civil protection operations within Kosovo; and to assist the civil authorities in responding to natural disasters and other emergencies’. Republic of Kosovo (n.d.) ‘Kosovo Security Force’. Retrieved from http://www.rks-gov.net.

[31]Assembly of the Republic of Kosovo, ‘Law on the Ministry for Kosovo Security Forces’, Article 3 (10-C). Law No. 03/L-045 (13 March 2008).

[32] Kosovo Force, ‘NATO Liaison and Advisory Team Change of Command’ (14 January 2015). Retrieved from http://www.aco.nato.int/kfor.

[33] NATO, ‘NATO’s role in Kosovo’ (2014).

[34] J. DeRosa, ‘Strategic Defense Review of the Republic of Kosovo’, GAP Policy Paper (2013) p. 28.

[35] NATO, ‘NATO’s role in Kosovo’ (2014).

[36] In 2006, prior to the declaration of independence, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) commissioned an Internal Security Sector Review (ISSR). The report suggested a mechanism for the creation of a Kosovo Defence Force. Already in 2006 it was recommended to disband the KPC and to form a Kosovo Defence Force. The name of the Force was later renamed in the KSF, due to ongoing regional and international sensitivities about Kosovo having a national army while not all states recognised it as an independent state; A. Welch, ‘Apprising the 2006 Kosovo Internal Security Sector Review – Part One’ (10 June 2014). Retrieved from http://www.ssrresourcecentre.org.

[37] Republic of Kosovo, ‘Analysis of the Strategic Security Sector Review of the Republic of Kosovo’ (March 2014), p. 56.

[38] After national elections on 8 June 2014, Kosovo entered a political deadlock that lasted slightly more than six months due to disagreement over the positions of the Assembly Speaker and Prime-Minister between a united opposition block and the winner of the elections, the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK). Mid-November the second largest political party, the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), broke away from the opposition coalition to form a government with the PDK that presented itself to the Kosovo Parliament on 9 December 2014.

[39] ‘The future of Kosovo Armed Forces, which has no other alternative, remains a primary task of the new Parliament, an institution so important and necessary for the country and its citizens, which will thus engender Kosovo’s OWN defence force, will complete the consolidation of our state and become a contributor to the collective security of Europe.’ (President Jahjaga, ‘President Jahjaga’s speech on the occasion of Kosovo Security Force Day’ (26 November 2014). Retrieved from http://www.president-ksgov.net).

[40] E. Pond, ‘The EU’s test in Kosovo’, in: The Washington Quarterly, Autumn (2010) p. 100-101; N. van Willigen, ‘Kosovo: instabiel en niet soeverein’, in: Internationale Spectator (2008) (62) no. 7/8, p. 379.

[41] N. van Willigen, ‘Kosovo: instabiel en niet soeverein’, in: Internationale Spectator (2008) (62) no. 7/8, p. 380.

[42] BalkanInsight, ‘Serbia: Conditions not right for KFOR withdrawal’ (6 August 2009). Retrieved from http://www.balkaninsight.com.

[43] Incidents included protests at the Jarinje checkpoint (Gate 1, near the Serbian border town of Raska) and the actual burning of the border crossing checkpoint at Jarinje in 2011. BalkanInsight, ‘Timeline: Tensions in Kosovo North’ (15 September 2011); BalkanInsight, ‘KFOR to respond with force if attacked in Kosovo’ (29 September 2011); BalkanInsight, ‘Dozens reported injured in North Kosovo stand-off’ (20 October 2011).

[44] BalkanInsight, ‘Attack on NATO forces in Kosovo condemned’ (19 June 2012).

[45] Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, ‘Tales from Mitrovica: life in a divided Kosovo town’ (15 February 2013). Retrieved from www.rferl.org.

[46] European Union - European External Action Service, ‘Serbia and Kosovo reach landmark deal’ (19 April 2013). Retrieved from http://eeas.europa.eu.

[47] European Union - European External Action Service, ‘Serbia and Kosovo reach landmark deal’ (19 April 2013). Retrieved from http://eeas.europa.eu.

[48] European Union – European External Action Service, ‘First Agreement of Principles Governing the Normalisation of Relations’ (19 April 2013).

[49] M. Nic, J. Cingel, ‘Serbia’s relations with NATO: the other (Quieter) game in town’, Central European Policy Institute (January 2014).

[50] Statements of Oliver Ivanovic, former state secretary in the Ministry for Kosovo and Metohija, and Dragan Sutanovac, onetime Serbian Minister of Defence, in UNMIK, ‘Ivanovic: NATO should not call on strengthening of KSF’ (10 July 2013); UNMIK, ‘The establishment of Kosovo’s army threatens the Kumanovo Agreement’ (4 December 2014).

[51] Open issues in the Brussels Agreement are the establishment of the Association of Serbian Municipalities, the delineation of Serbian jurisdiction in northern Kosovo and the dismantling of the so-called ‘civil protection corps’. On the technical level of the dialogue, recently progress has been made on Integrated Border Management (IBM) and energy distribution: Group for Legal and Political Studies, ‘The implementation of the EU facilitated agreement(s) between Kosovo and Serbia – a short analysis of the main achievements and challenges’ (August 2014).

[52] UN Security Council, ‘Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo’, S2014/773, p. 2-3; 9-10 (31 October 2014).