The Gerasimov doctrine is often described as a form of hybrid warfare, which in turn is a new buzzword for describing the current Russian notion of conducting operations, most recently displayed in Crimea, Eastern Ukraine and Syria. The doctrine appeals to the adaptive use of conventional (military) and especially non-conventional employ of military assets or non-military means in the pursuit of political objectives. As such, it poses (counter)intelligence challenges for NATO and its member states. NATO has acknowledged that a comprehensive approach is needed to counter the multi-dimensional nature of hybrid threats. Several recommendations can be made, such as giving special attention to (the creation of) permanent All Source Intelligence Cells on the operational and tactical levels, solely focusing on the Russian Federation and its hybrid threats.

Captain Royal Netherlands Army E.H.F. Donkersloot MA*

In 2013, Russian General Valery Gerasimov published an article entitled The Value of Science is in the Foresight: New Challenges Demand Rethinking the Forms and Methods of Carrying out Combat Operations.[1] His ideas in this article are often referred to as the ‘Gerasimov doctrine’ by the West, even though it is not a formal military doctrine of the Russian Federation. In his article, General Gerasimov even states it was the West – and not the Russian Federation – which led the way in pioneering political-military operations focusing on destabilizing hostile regimes.[2] He advocates the use of a modern version of ‘partisan warfare’: targeting weaknesses and avoiding overt confrontation until the final stages of a campaign or when ambiguous operations are no longer feasible.[3] The use of the information domain like the internet and (social) media has become an important instrument of warfare, according to Gerasimov. The Gerasimov doctrine is often described as a form of hybrid warfare, which in turn is a new buzzword for describing the current Russian notion of conducting operations, most recently displayed in Crimea, Eastern Ukraine and Syria. A current NATO definition of a hybrid threat is ‘[…] one posed by any current or potential adversary including state, non-state and terrorists, with the ability, whether demonstrated or likely, to simultaneously employ conventional and non-conventional means adaptively, in pursuit of their objective.’[4]

In sum, the Gerasimov doctrine appeals to the adaptive use of conventional (military) and especially non-conventional employ of military assets or non-military means in the pursuit of political objectives. This ‘new way of war’ and its asymmetrical means bypasses or even neutralizes the Western (military) capacities and exploits vulnerabilities of Western societies. It is a way of war that uses political technologies.[5] The role of non-military means in achieving political and strategic goals has grown.[6]

In her University of Ottawa research paper, Katie Abbot argues that NATO must improve and increase intelligence gathering capabilities and situational awareness in regard to deterring and becoming resilient to hybrid warfare tactics.[7] Like Abbot, most researchers and professionals agree that a hybrid threat requires a comprehensive response that goes beyond traditional military capabilities.[8] Furthermore, there is consensus that security services (intelligence services, police forces and border guards) are extremely important as they are the first line of defence.[9] Frank Hoffman, senior researcher at the Center for Strategic Research, states that the implications of hybrid warfare for the intelligence community may be the most profound of all and that further examination of this challenge should be undertaken to ensure that military commanders and policy makers gain insight into adaptive enemies.[10] This article is a further analysis that seeks an answer to the question to what extent the Gerasimov doctrine of the Russian Federation poses (counter)intelligence challenges for NATO and its member states.

General Valery Gerasimov (right) during talks about operations in Syria with his American and Turkish counterparts Marine Corps General Joseph Dunford Jr. (left), and General Hulusi Akar (centre) (Antalya, March 6, 2017) Photo U.S. Navy D. Pineiro

In the first section the Gerasimov doctrine, or so-called Russian model of hybrid warfare, will be clarified briefly. The second section focuses on the Intelligence Cycle and (counter)intelligence challenges for NATO (and its member states). Conclusions will be given in the third section and recommendations are put forward in the fourth section. It is important to note that this research mainly zooms in on non-military options and challenges for the NATO intelligence community when facing Russian interference in Western societies. However, some military implications and challenges of the hybrid threat will be discussed, since the military and its intelligence community play an important role in countering it. Moreover, this article will largely focus on both short and long-term challenges for NATO on the political and strategic levels. Nonetheless, some issues are applicable to lower operational levels as well. The challenges and recommendations presented are not ‘the’ solution to counter the hybrid threat posed by the Russian Federation. However, this article will give the intelligence communities of NATO member states some useful recommendations. As mentioned before, the Gerasimov doctrine is not an official Russian Federation doctrine. Nonetheless, within the scope of this article the term Gerasimov doctrine refers to hybrid warfare campaigns conducted by Moscow.

Characteristics of hybrid warfare and the Gerasimov doctrine

Hybrid warfare has been an integral part of the historical landscape since ancient times.[11] This section briefly examines the common characteristics of hybrid warfare and specifically those that are applicable to the Gerasimov doctrine. There are various definitions and different terms that refer to (the history of) hybrid warfare, but most scholars ultimately seem to agree with Frank Hoffman’s definition: ‘Hybrid threats incorporate a full range of different modes of warfare including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, terrorist acts including indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder. Hybrid wars can be conducted by both states and a variety of non-state actors. These multi-modal activities can be conducted by separate units, or even by the same unit, but are generally operationally and tactically directed and coordinated within the main battle space to achieve synergistic effects in the physical and psychological dimensions of the conflict. These effects can be gained at all levels of war.’[12] The bottom line is that a variety of tools, both military and non-military, are used to further political goals.[13] The same goes for the Gerasimov doctrine.

Within the Gerasimov doctrine the role of non-military means, such as political, economic, informational and humanitarian measures, are of the utmost importance. These are supplemented by military means of a concealed character, including carrying out actions of informational conflict and the actions of special operations forces.[14] For example, the Gerasimov doctrine combines different types of threats including subversion, physical and information provocation, economic threats, cyber attacks, posturing with regular forces and the use of Spetsnaz (Russian special operations forces). Furthermore, the Gerasimov doctrine incorporates the use of paramilitary and political organizations, terrorists and criminal elements, supported by the intelligence community of the Russian Federation.[15] Also, the doctrine includes different types of operations, such as unconventional, information, psychological and cyber operations, as well as security forces assistance and strategic communication.[16] In addition, the Russian phenomenon of maskirovka (‘a little masquerade’) is very applicable to the Gerasimov doctrine as it involves disguise, deception, decoys and disinformation to deceive adversaries.[17] Secretly a desired political, economic or military position is created by using propaganda and agitation, with the purpose of influencing decision-making processes of a certain target audience or to influence public opinions in favour of Russian political goals. Plausible deniability is an important part of this principle. Without going into detail, the above-mentioned methods were – and currently are – extensively used in Georgia, Estonia, Crimea, Eastern Ukraine and Syria.

Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe General Philip Breedlove sees cyber, information warfare, surprise, deception, extensive use of proxy and special forces as central elements of hybrid warfare. This threat, including unconventional and conventional methods, is what Breedlove refers to as hybrid war.[18] A Dutch definition describes hybrid warfare as follows: ‘Hybrid warfare generates very complex threats which change in shape and appearance. It regularly consists of an integrated use of conventional and non-conventional means, both overt and covert, including (para)military and civilian actors in order to create ambiguity and to target vulnerabilities of an adversary to achieve geopolitical and strategic goals. Deception and manipulated information operations play an important role in hybrid warfare.’[19] Another recently published Dutch definition is even more specific: ‘Hybrid warfare is the Russian Federation’s way of synchronizing formal and informal deployment of all PMESII[20] assets at the operational level to further a specific political strategic goal without transgressing into a formal state of war between states.’[21]

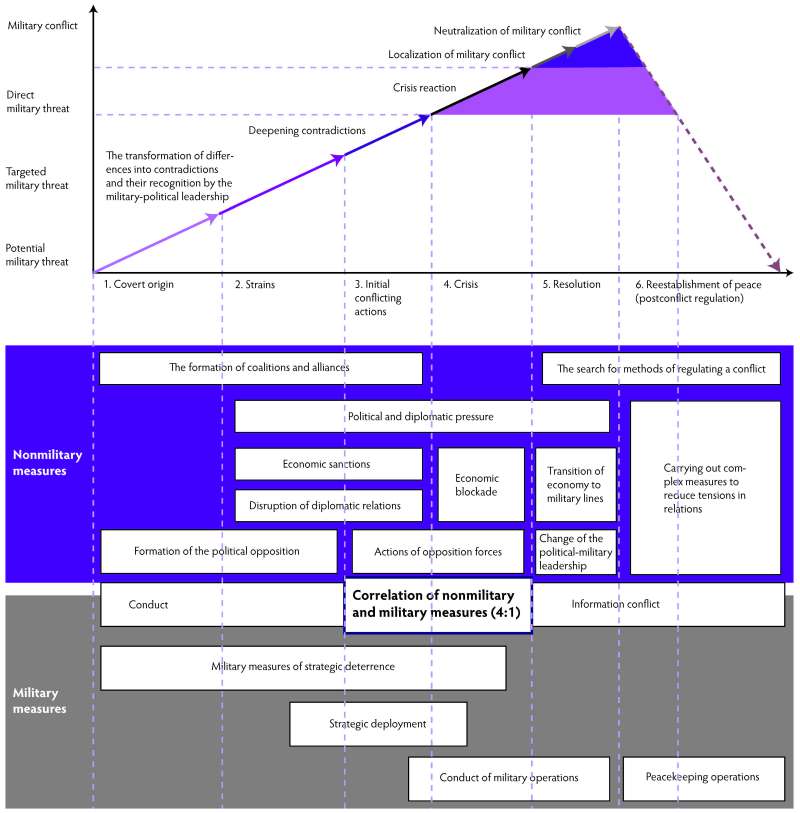

Again, it becomes clear that the Russian model of hybrid warfare includes both conventional and non-conventional means – on a 1:4 ratio – for political ends. Figure 1 shows several measures (connected to different stages) used in the Gerasimov doctrine.

Figure 1 Graph of the Gerasimov doctrine (Source: Military Review, January-February 2016, p. 35. Reprinted with permission)[22]

After a brief analysis of the Gerasimov doctrine it can be concluded that by applying deception, psychological and information operations Russia creates a curtain of ambiguity that obscures reality and hinders a calculated NATO response.[23] In addition, it is important to note that the threats posed by the Russian way of conducting (military) operations are not bound by physical or digital boundaries. The Russian operations are mostly designed to disrupt ‘hostile’ societies and fuel internal polarization in target nations. To facilitate this, the Russian security and intelligence apparatus plays an important role when it comes to gathering information, but blackmail, subversion, assassination and sabotage are also central to their mission.[24] All above-mentioned elements of the Gerasimov doctrine are designed to reach several desired political end states, which cannot be reached by military means (alone). An important political goal is to maintain Russia’s role as a key player in the international political arena. Furthermore, the Russian Federation seeks to actively influence or even incorporate former Soviet states, the so-called Near Abroad. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 is the best example of such a campaign. Finally, Moscow seeks to put a stop to NATO’s expansion to the East and to keep Western ideas as far away from Russia as possible. Russian leaders operate with a zero-sum mindset: whatever one side gains, the other side loses.

The Gerasimov doctrine is a so-called whole-of-society approach that causes a shift in means and domains. It poses a challenge to the Western way of war due to the unfamiliarity with its ways, means, effects and goals.[25] The Russian way of conducting operations is aimed at dividing, demoralizing and distracting a target nation. One of the key challenges in addressing hybrid warfare is to identify subversive activity within a nation and to successfully attribute this activity to a group or state. National preparation and readiness against this kind of threat in its earliest stage are critical.[26] Indicator and warning systems and actionable intelligence are essential elements in identifying subversive activity posed by the Russian Federation. Mark Galeotti, senior researcher at the Institute of International Relations in Prague, made a clear statement which underlines NATO’s need for robust intelligence systems to counter Russia’s hybrid operations: ‘Given Moscow’s determination to cloak its true capabilities and intents, and also to operate below and around the existing thresholds for direct military responses, any effective new policy (…) depends on a timely, nuanced, and accurate understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of this ‘new way of war’.[27] This is where (counter)intelligence comes into play.

Sergey Lavrov, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, addresses a high-level UN Security Council meeting: an important goal of the Russian Federation is to remain a key player in the international political arena. Photo United Nations

Even though the Russian Federation is not in a state of war with NATO or one of its member states, it’s more than obvious that an ‘intelligence conflict’ is ongoing and real. This means that societies as a whole – and intelligence services in particular – have to respond to specific threats on a day-to-day basis. NATO is committed to effective cooperation and coordination with partners and relevant international organizations, in particular the EU, in efforts to counter hybrid warfare.[28] Nonetheless, there are specific vulnerabilities in Western societies that Moscow is eagerly exploiting. The fundamental challenges are to fully understand Russia’s capabilities and what they involve and what the deterrence and response options are.[29]

The (counter)intelligence challenges

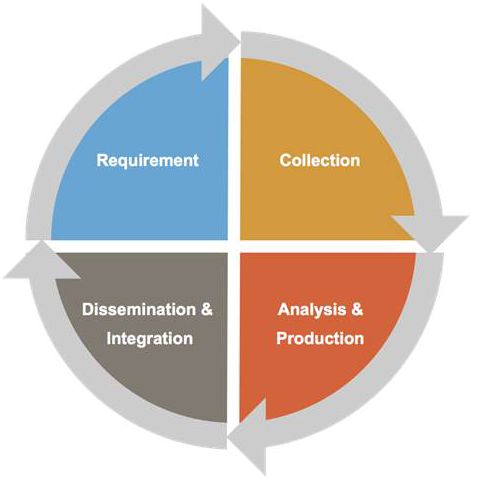

Before discussing the intelligence challenges that come with a hybrid threat, it is necessary to describe the different stages of the Intelligence Cycle predominantly used by NATO and its member states. The Intelligence Cycle is a general (intelligence) operations framework with different characteristics, ranging from asymmetric warfare to full-scale war. This means it is also applicable to a hybrid warfare environment and therefore important to describe within the scope of this article.

The Intelligence Cycle

The initial stage of the Intelligence Cycle is planning and direction or requirement. In this stage policy makers state their intelligence requirements. The next stage is intelligence collection: going after the information that planners and policy makers designate using various sources, sensors and therefore different ‘ints’.[30] In the third stage of the cycle, analysis and production, the collected intelligence must be converted into usable information. Intelligence analysts convert raw information into assessments, which in turn result in reports, briefings or other formats in a certain required language. Finally, intelligence reports must be distributed to policy makers and other clients.[31] Whether or not the information can be shared with other (member) states depends on the classification of the product. The Intelligence Cycle is indefinite, because answers to requirements lead to new intelligence requirements. Therefore, the cycle is an open-ended stream of information demands and answers to those demands. Lastly, it is important to note that counter-intelligence activities are not incorporated in the cycle. A definition of counter-intelligence will be given in the section below.

Figure 2 The Intelligence Cycle

(Counter)intelligence challenges for NATO

According to NATO, the alliance faces a range of security challenges: ‘Russia’s aggressive actions, including provocative military activities in the periphery of NATO territory and its demonstrated willingness to attain political goals fundamentally challenge the Alliance (...) Our [NATO’s] ability to understand, track and, ultimately, anticipate, the actions of potential adversaries through Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities and comprehensive intelligence arrangements is increasingly important. These are essential to enable timely and informed political and military decisions. We have established the capabilities necessary to ensure our responsiveness is commensurate with our highest readiness forces.’[32]

Several NATO member states recently identified three priorities to prepare for – and eventually counter – the hybrid threat from the East. The first priority is to enhance the resilience of member states, EU and NATO institutions, and other institutions. The second is to develop procedures and policies to enable effective responses, and the third priority is to enhance early recognition of a hybrid attack to enable early action.[33] The latter priority depends on actionable intelligence including an integrated approach, because hybrid warfare operations mostly come with denial, deception and an overload of (dis)information. This makes intelligence gathering and analysis more important, but also more challenging. Therefore, operations conducted by the Russian Federation in the light of the Gerasimov doctrine result in specific challenges for NATO’s intelligence community.

In this section NATO’s expected intelligence shortcomings will be highlighted in a random order. As mentioned before, the Gerasimov doctrine mainly makes use of non-military and whole-of-society options and therefore (new) challenges for the NATO intelligence community can be defined. The challenges posed by the Gerasimov doctrine noted below are the most significant ones and are the subject of in-depth review.

The first challenge in hybrid wars is that a degree of understanding[34] and cultural sensitivity must be acquired by the intelligence community, with a deep understanding of the historical and cultural context.[35] Galeotti states that: ‘(…) it is crucial to think in Russian – in other words, to understand Moscow’s motivations, and its understanding of the current confrontation.’[36] This is important while practicing intelligence in general, but this is even more important when countering a hybrid threat since this is a whole-of-society phenomenon. In other words, situational awareness is a principal – and crucial – step in order to understand a (Russian) hybrid threat and ultimately a step towards thorough and successful intelligence analyses and production by NATO. Situational awareness refers to the cognitive processes involved in perceiving and comprehending the meaning of a given environment, leading to the ability to make timely and sound decisions regarding future events in that environment.[37]

Another implied and connected task is to reduce the expected shortage of skilled Russian language experts within NATO. This shortage results in endemic ethnocentrism and lack of cultural sensitivity and it hampers effective collection and analyses efforts.[38] Overall, a lack of situational awareness and knowledge of Russian society are obstacles for information processing and lead to unmotivated biases. This is a concern for NATO, primarily in the collection, analysis and production stages of the Intelligence Cycle.

People at a bookstall in Moscow: in order to acquire cultural sensitivity and a deeper understanding of the historical context, the intelligence community will have to ‘think in Russian’. Photo ANP

The second issue confronting NATO’s intelligence services, specifically in the collection phase of the Intelligence Cycle, is the availability of large amounts of open source information in the public sphere, especially information on the internet. This may be a quantitative rise, but does not infer any similar qualitative improvement.[39] For example, Social Media Intelligence (SOCMINT) is a task the intelligence community faces in the light of the Gerasimov doctrine, because the Russian Federation extensively uses social media in its information campaigns around the globe in order to influence Western societies. Russia is a player in every social media space and conducts immense information operations using social media to flood Western societies with (dis)information.

Meanwhile, Western secret services have the urge to create a ‘cyber situational awareness’ when it comes to social media. SOCMINT provides this near real-time situational awareness. Such data include insights into location, social network(s), relationship status, political preferences, sexual preferences, shopping habits, devices used to browse the internet and much more. By merging these sources, for instance by using algorithms, mathematical formulas and so-called data mining techniques (a process of discovering patterns in large amounts of data), a comprehensive image of persons, groups and networks can be created.[40] It is a necessity for NATO to adopt sophisticated open source collection strategies and above all the needed technology and methodology for analysis and production. Next to public intelligence organizations, private intelligence agencies can assist NATO in these collection and analyses activities, since they are likely to have experience in using the required methods and techniques.

Connected to the above-mentioned issue, a third challenge for NATO is to initiate awareness campaigns concerning Russia’s information warfare operations. General Gerasimov stated that the falsification of events and control of the media are among the most effective methods of asymmetric warfare.[41] Social media have been used more and more strategically by multiple state and non-state actors to create effects in both the virtual and physical domains.[42] The Russian Federation has (state-owned) media offices that affect the internet, other social media and conventional news gathering in order to insert propaganda, present a different view, provide reasonable doubt and shape popular opinion in Western societies. Russia has crafted a state media force of opinion shapers (also known as the Troll Army) which routinely circulates misinformation or false narratives at home and abroad.[43] The purpose is to create doubt and mistrust towards and within Western societies. Another purpose is to slow down decision-making processes affecting the unity and cohesion of alliances such as NATO.[44] NATO’s digital, transparent, and globally interconnected society has weaknesses that are being exploited by the Russian Federation.[45] NATO should enhance awareness, not only amongst policy makers and the intelligence community but primarily amongst the general public, as they are the primary target audience of the Russian Federation’s propaganda. If the general public in Western societies is aware of Russia’s information operations efforts, this is the first step towards diminishing their effect.

The fourth area where NATO must engage is intelligence sharing among member states. Sharing occurs when a state communicates intelligence with another state.[46] These sharing arrangements and intelligence partnerships have become essential, specifically when countering hybrid threats. The NATO Intelligence Fusion Centre in Molesworth (United Kingdom) and NATO’s Joint Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (JISR) initiative, are examples of successful intelligence fusion and sharing among member states in order to maintain the appropriate situational awareness. While respecting the principles of inclusiveness and autonomy of each decision-making process, a far deeper and broader sharing of intelligence amongst member states ought to be aspired to. Not all intelligence is to be shared. Nonetheless, the rule of thumb should become ‘share, unless’ instead of ‘don’t share, unless’, according to a Dutch think tank.[47] Declassification of information is another tool to share intelligence more easily. In addition to the sharing of information between member states, sharing of information within countries and between different agencies and departments is needed. Hence, a hybrid threat requires a hybrid response. Therefore, interagency cooperation is a crucial part of the intelligence sharing challenge for NATO member states.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg addresses the 2016 Warsaw Summit Experts’ Forum, where the challenges of the Alliance’s Eastern and Southern flanks, including potential hybrid threats, were discussed. Photo NATO

A fifth challenge lies in counterintelligence (CI) efforts. The U.S. government’s definition of CI is: ‘Counterintelligence means information gathered and activities conducted to identify, deceive, exploit, disrupt or protect against espionage, other intelligence activities, sabotage or assassination for or on behalf of foreign powers, organizations or persons or their agents, or international terrorist organizations or activities.’[48] There are different (national) approaches to conducting CI operations, varying from ‘offensive’ active operations to more ‘defensive’ operations. The Gerasimov doctrine includes offensive information warfare, psychological, ideological, diplomatic, and economic measures, but also special operations conducted to mislead political and military leaders. Coordinated offensive measures are carried out by Russian diplomatic channels, media, and top government and military agencies. The measures include leaking false data, orders, directives, and instructions.[49] This results in challenges for NATO’s defensive operations, because it is not easy to identify useful indicators for effective counterintelligence operations and – eventually – to counter a hybrid threat. There is a demanding task for NATO and its intelligence community to counter unknown and invisible threats posed by the Russian Federation, especially if they are characterized by operations to mislead NATO.

The final challenge involves cyber security. NATO recognized cyberspace as a ‘domain of operations’ at the Warsaw Summit in July 2016.[50] Cyber security is the body of technologies, processes and practices designed to protect networks, computers, programs and data from attack, damage or unauthorized access.[51] The Russians consider combat actions in cyberspace as cyber actions carried out by states, or groups of states or organized political groups against cyber infrastructure that are part of a military campaign.[52] Thus, the Gerasimov doctrine embraces cyber activities, which are crucial to Russian offensive disinformation and strategic cyber campaigns. For example, propaganda is a cheap and effective form of cyber attack. Provocative information that is removed from the internet can reappear in a few seconds.[53] Another example of cyber activity is social engineering, which basically refers to psychological manipulation of people into performing actions or leaking confidential information. The Russian intelligence community plays a central role in cyber warfare. Therefore, NATO must develop its ability to prevent, detect, and defend against cyber attacks initiated by the Russian Federation. Cyber defence must be geared towards handling every possible enemy, everywhere and anytime.[54] Still, detection and prevention of cyber activities remain difficult tasks and therefore cyber security remains an important issue for NATO.

Conclusion

The Russian Federation’s Gerasimov doctrine poses severe (counter)intelligence challenges for NATO and its member countries and they are related to all stages of the Intelligence Cycle. Firstly, a degree of understanding and cultural sensitivity must be acquired by NATO’s intelligence community, with a deeper understanding of the Russian historical and cultural context. Moreover, the availability of large amounts of open source information in the public sphere requires permanent action by the intelligence community. The development of sophisticated SOCMINT collection and production strategies is a precondition to effectively deal with open source information. Other challenges are to identify useful indicators for effective cyber defence and counterintelligence operations, closely together with intensification of intelligence sharing among member states and among different departments within member states. Lastly, NATO countries should improve awareness campaigns concerning information warfare and identifying ‘fake news’. This is not only the field of intelligence organizations, but should, as a whole-of-society approach, in fact primarily be addressed by the general public on a day-to-day basis.

The above-mentioned challenges require a comprehensive and transnational response that goes beyond traditional military capabilities. In addition, sophisticated and flexible intelligence approaches are essential in understanding and countering hybrid adversaries. The following section contains recommendations for NATO and its intelligence community.

Recommendations

Intelligence recommendations

In 2011, NATO acknowledged that a comprehensive approach was needed to counter the multi-dimensional nature of hybrid threats. This approach promotes the coordinated application of the full range of collective resources available. Also, NATO officials stated that countering hybrid threats requires first of all a new understanding of such threats and the innovative use of existing capabilities to meet these new tasks, rather than new hardware.[55]

To meet the challenges, several intelligence recommendations to NATO and its member states can be made.

A first recommendation is to give special attention to (the creation of) permanent All Source Intelligence Cells on the operational and tactical levels, solely focusing on the Russian Federation and its hybrid threats and preferably deployed in areas bordering on the Russian Federation (for example in the Baltic States). Furthermore, NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence battle groups deployed in the Baltic States require integrated intelligence units on the tactical level. For collection efforts, these entities require robust intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities, which are fundamental for effective situational awareness, strategic foresight and early warning.[56] For thorough – and less biased – intelligence production, experts that have the requisite situational awareness, cultural sensitivity, linguistic skills and experience, will have to be recruited. Moreover, private intelligence agencies must be integrated. Many firms are specialized in a wide range of activities from language translations to analysis. So-called intelligence outsourcing is needed to improve collection and production techniques. A sophisticated screening of these private intelligence agencies and its employees is, however, an essential precondition. Another crucial point in these government-private sector relationships is the need for non-disclosure regulations to protect (classified) information.

Dutch military personnel, taking part in the Enhanced Forward Presence operations in Lithuania, during a briefing: NATO’s military units should constantly remind their soldiers of information warfare threats. Photo MCD, G. van Es

A second recommendation, also for collection purposes, is the actual sharing of intelligence between NATO member states. Hence, the hybrid threat demands more efficient collection, processing, sharing and merging of all sources of intelligence within and between nations, regional and international organizations, NGOs and partners.[57] It has been argued that ‘ubiquitous, useful and unclassified (U3) information’ is a key enabler in understanding and predicting Russian moves.[58] Furthermore, reinforcing links between domestic agencies, including law enforcement, will allow member states to better address a range of transnational security threats and shared issues.[59] Nonetheless, when it comes to sharing intelligence it is of the utmost importance that sources are protected at all times. In general, improving such operational security measures will result in mutual trust between member states. Mutual trust and political will are essential elements for intelligence sharing, which in turn is a force multiplier in the battle against a hybrid threat.

Other recommendations stemming from the research

A more general recommendation concerns training and education at all levels. The Gerasimov doctrine poses a variety of ‘new’ unconventional threats. In general, the public should be aware of those threats, particularly the information flow produced by the Russian Federation through the internet, social media and conventional (state-owned) news outlets. The public should be informed that these tools are being used to insert propaganda, present a different view, provide reasonable doubt and shape popular opinion. NATO’s military units should also remind their soldiers of these information warfare threats. Currently, the flow of misleading and inaccurate stories is so overwhelming that NATO has established special offices to identify and refute disinformation, particularly claims made by Russia.[60] Also, NATO has a range of capabilities to inform, influence, and persuade the selected target audiences.[61] NATO has to make use of these capabilities and (rapidly) inform the public with ‘the truth’ when false information or ‘fake news’ is published by the Russian Federation. Media may go for rapid publication instead of time-consuming fact checking.[62] This has to be prevented by making Western media (and intelligence analysts) aware of the multiple disinformation efforts conducted by the Russian Federation. In the end, this will have a positive effect on NATO and its (counter)intelligence efforts, since Russia’s efforts to further political goals will be hampered.

Other training and education efforts should be initiated in order to improve end user education and awareness concerning cyber security (operational security and military security). Moreover, it is crucial to internationalize cyber security as every interconnected system is as strong as its weakest link. End user training and education is an important element in preventing social engineering, but hardcore defensive systems are the first line of defence in eventually preventing and disrupting cyber attacks directed by the Russian Federation.

To close

NATO and its intelligence community have to confront serious challenges deriving from the hybrid threats posed by the Gerasimov doctrine. In order to effectively deal with them, NATO should implement the proposed recommendations at short notice. However, these actions will only be effective if supplemented by sufficient funding and the political will to actually implement the changes needed. Nonetheless, the Gerasimov doctrine is flexible and adaptive by nature and will likely confront NATO with new challenges in the (near) future. The NATO intelligence community has the important – but extremely difficult – task to assist policy makers in engaging such hybrid threats.

The Gerasimov doctrine implies actions that are unpredictable and hard to monitor because there are very few identifiable indicators at hand, resulting in many unknown-unknowns. By implementing the above-mentioned recommendations NATO can make small steps towards understanding the hybrid threat and the formulation of known-unknowns. That may form the basis for new intelligence requirements and specific intelligence collection plans in the PMESII domain. Establishing this would be a major step for NATO towards understanding and ultimately countering the Gerasimov doctrine effectively.

* Erik Donkersloot is a Captain in the Royal Netherlands Army currently employed as Staff Officer in the Fire Support Command. He holds an MA degree in International Relations from Utrecht University. This article is based on an essay he wrote for his Master’s degree in Military Strategic Studies at the Royal Netherlands Defence Academy.

[1] Charles K. Bartles, ‘Getting Gerasimov Right’, in: Military Review (January 2016) 30.

[2] Mark Galeotti, ‘Hybrid Warfare or Gibridnaya Voina? Getting Russia’s non-linear military challenge right’ (Mayak Intelligence, 2016) 5.

[3] Mary Ellen Connel and Ryan Evans, ‘Russia’s Ambiguous Warfare and its implications for the U.S. Marine Corps’, CNA (May 2015) 4.

[4] In: Alex Geers, ‘Hybrid warfare WTF?’, in: Infanterie (1-2016) 42.

[5] Galeotti, ‘Hybrid Warfare or Gibridnaya Voina?’, 8-10, 12.

[6] Ibidem, 21.

[7] Katie Abbot, ‘Understanding and Countering Hybrid Warfare: Next Steps for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’, University of Ottawa (March 2016) 30.

[8] Jelle van Haaster and Mark Roorda, ‘The Impact of Hybrid Warfare on Traditional Operational Rationale’, in: Militaire Spectator 185 (2016) (4) 176.

[9] In: Abbot, ‘Understanding and Countering Hybrid Warfare’, 23.

[10] In: Frank G. Hoffman, ‘Conflict in the 21st Century: The rise of hybrid wars’ (Arlington, Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2007) 47.

[11] Keir Giles, ‘Russia’s ‘New’ Tools for Confronting the West. Continuity and Innovation in Moscow’s Exercise of Power’ (London, Chatham House, 2016) 7: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/publications/2016-03-russia-new-tools-giles.pdf.

[12] Hoffman, ‘Conflict in the 21st Century’, 8.

[13] ‘De Groene Mannetjes’ (‘Little Green Men’) editorial in: Militaire Spectator 184 (2015) (5) 210-211.

[14] In Moscow’s shadows, ‘The ‘Gerasimov Doctrine’ and Russian Non-Linear War’, https://inmoscowsshadows.wordpress.com/2014/07/06/the-gerasimov-doctrine-and-russian-non-linear-war (consulted on 16 November 2016).

[15] Robert A. Newson, ‘Counter-Unconventional, Warfare Is the Way of the Future. How Can We Get There?’ (23 October 2014), http://blogs.cfr.org/davidson/2014/10/23/counter-unconventional-warfare-is-the-way-of-the-future-how-can-we-get-there (consulted on 12 November 2016).

[16] A.J.C. Selhorst, ‘Russia’s Perception Warfare. The development of Gerasimov’s doctrine in Estonia and Georgia and it’s application in Ukraine’, in: Militaire Spectator 185 (2016) (4) 153.

[17] ‘De Groene Mannetjes’, editorial in: Militaire Spectator 184 (2015) (5) 210-211.

[18] Guillaume Lasconjarias and Jeffrey A. Larsen (eds.), NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats (Rome, NATO Defence College, 2015) xxii.

[19] Ramon Jansen (ed.), ‘Countering Hybrid Warfare; de militaire bijdrage aan veiligheid in een wereld met hybride dreigingen’ (4 November 2016) 7.

[20] Political, Military, Economic, Social (Cultural), Infrastructure and Information.

[21] Geers, ‘Hybrid warfare WTF?’, 43.

[22] Bartles, ‘Getting Gerasimov Right’, 35.

[23] John R. Davis Jr., ‘Continued Evolution Of Hybrid Threats’, in: The Three Swords Magazine (28/2015) 22.

[24] Mark Galeotti, ‘Hybrid Warfare or Gibridnaya Voina? Getting Russia’s non-linear military challenge right’ (Mayak Intelligence, 2016) 64.

[25] In: Selhorst, ‘Russia’s Perception Warfare’, 150.

[26] Lasconjarias and Larsen, ‘NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats’, xxii.

[27] Galeotti, ‘Hybrid Warfare or Gibridnaya Voina?’, 15.

[28] NATO, Warsaw Summit Communiqué (9 July 2016), http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm,

(consulted on 29 June 2017).

[29] Galeotti, ‘Hybrid Warfare or Gibridnaya Voina?’, 70.

[30] Main categories of intelligence: Human Intelligence (HUMINT), Signals Intelligence (SIGINT), Open Source Intelligence (OSINT), Imagery Intelligence (IMINT), Technical Intelligence (TECHINT), Cyber Intelligence (CYBINT) and Geospatial Intelligence (GEOINT).

[31] Loch K. Johnson, ‘National Security Intelligence’, in: Loch K. Johnson (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence (New York, Oxford University Press, 2010) 12-21.

[32] NATO, Warsaw Summit Communiqué (9 July 2016), http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm,

(consulted on 29 June 2017).

[33] Jansen (ed.), ‘Countering Hybrid Warfare’, 3, 27.

[34] Understanding is defined as the perception and interpretation of a particular situation in order to provide the context, insight and foresight required for effective decision-making.

[35] Hoffman, ‘Conflict in the 21st Century’, 51.

[36] Galeotti, ‘Hybrid Warfare or Gibridnaya Voina?’, 76.

[37] Michael D. Matthews et al, ‘Situation awareness requirements for infantry platoon leaders’, Military Psychology 16 (2004) 149.

[38] Uri Bar Joseph and Rose McDermott, ‘The Intelligence Analyses crisis’, in: Loch K. Johnson (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence, 362.

[39] Stevyn D. Gibson, ‘Open Source Intelligence’, in: Robert Dover, Michael S. Goodman and Claudia Hillebrand (eds.), Routledge Companion to Intelligence Studies (London, Routledge, 2014) 129.

[40] Van Haaster and Roorda, ‘The Impact of Hybrid Warfare’, 176-177.

[41] Galeotti, ‘Hybrid Warfare or Gibridnaya Voina? 37.

[42] Thomas Nissen, ‘Social media’s role in hybrid strategies’ (Riga, NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, 2016) 5.

[43] Stéfanie Babst, ‘What Mid-Term Future for Putin’s Russia?’ in: Guillaume Lasconjarias and Jeffrey A. Larsen (eds.), ‘NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats’, 26.

[44] Thomas Nissen, ‘Social media’s role in hybrid strategies’, 1.

[45] Van Haaster and Roorda, ‘The Impact of Hybrid Warfare’, 176.

[46] James Igoe Walsh, ‘Intelligence Sharing’, in: Robert Dover, Michael S. Goodman and Claudia Hillebrand (eds.), Routledge Companion to Intelligence Studies (London, Routledge, 2014) 290.

[47] Margriet Drent et al, ‘New Threats, New EU and NATO Responses’ (The Hague, Clingendael Institute, July 2015) 32.

[48] Paul J. Redmond, ‘The Challenges of counterintelligence’, in: Loch K. Johnson (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence, 537.

[49] Janis Berzins, ‘Russian New Generation Warfare: Implications for Europe’ (14 October 2014), http://www.europeanleadershipnetwork.org/russian-new-generation-warfare-implications-for-europe_2006.html (consulted on 10 November 2016).

[50] NATO CCDCOE, NATO Recognizes Cyberspace as a ‘Domain of Operations’ at Warsaw Summit, https://ccdcoe.org/nato-recognises-cyberspace-domain-operations-warsaw-summit.html (consulted on 23 March 2017).

[51] Definition of Cybersecurity, http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/cybersecurity (consulted on 11 November 2016).

[52] Monaghan, The New Politics of Russia, 81.

[53] Josef Schröfl et al, Hybrid and Cyber War as Consequences of the Asymmetry. A Comprehensive Approach Answering Hybrid Actors and Activities in Cyberspace – Political, Social and Military Responses (Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, 2011) 122.

[54] John Ferris, ‘Signals Intelligence in War and Power Politics, 1914-2010’ in: Loch K. Johnson (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence, 169.

[55] Michael Miklaucic, ‘NATO countering the hybrid threat’, http://www.act.nato.int/nato-countering-the-hybrid-threat (consulted on 11 November 2016).

[56] Dominic P. Jankovski, ‘Hybrid Warfare: A known unknown?’, (18 July 2016), http://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2016/07/18/hybrid-warfare-known-unknown/ (consulted on 11 November 2016).

[57] NATO, ‘Input to a New NATO Capstone Concept for the Military Contribution to Countering Hybrid Threats (Mons/Norfolk, NATO, 2010) 11.

[58] Giles, ‘Russia’s ‘New’ Tools for Confronting the West’, 62.

[59] Julio Miranda Calha, ‘Hybrid Warfare: NATO’s New Strategic Challenge?’ (Brussels, NATO Parliamentary Assembly, 2015) 9. http://www.nato-pa.int/default.asp?SHORTCUT=3778.

[60] Neil MacFarquhar, ‘A Powerful Russian Weapon: The Spread of False Stories’, in: The New York Times (28 August 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/29/world/europe/russia-sweden-disinformation.html.

[61] Christopher Paul and Miriam Matthews, ‘The Russian “Firehose of Falsehood” Propaganda Model. Why It Might Work and Options to Counter it’ (Santa Monica, RAND Corporation, 2016) 10.

[62] Van Haaster and Roorda, ‘The Impact of Hybrid Warfare’, 176-177.