Information has always been an integral part of conflict. Recent disinformation campaigns brought the information environment to the forefront in military planning and doctrine. How should military units operate in the information environment, how can they become successful in this domain? Experiences gained at 1 (German/Netherlands) Corps show the importance of strategic communication and other information capabilities in an integrated information effort.

Colonel Dr. Joris van Esch and Colonel Simon Hirst*

‘You might not see things yet on the surface, but underground, it’s already on fire’ – Indonesian writer Y.B. Mangunwijaya[1]

We all live in a world where the information revolution is widely considered a reality, in a world with a 24/7 news cycle, in which a short video of an arrest causes worldwide demonstrations, or where news, fake-news, and propaganda are an unmistakable part of our language, and in a world where our own actions are judged in an instant. In this world, a great body of knowledge on information has been developed over the years, including a lively discourse on the fragmentation of the infosphere, sensationalism, and its consequences for society. A recent RAND-report, for example, argued that the emergence of multiple technologies like artificial intelligence could change people’s fundamental social reality, threatening social coherence and democratic stability.[2]

Throughout the ages, information has also played a key role in conflicts. Clausewitz questioned whether war was to be considered as ‘just another form of expression of [the government’s] thoughts, another form of speech or writing.’[3] As an example, strategic narratives frame how actions are understood by different audiences, and interweave the trinity of the public, war, and politics.[4] Or the other way around, some even argue that social media have reshaped conflict itself and that it is not about whose army wins, but whose story wins.[5]

Integration of information into military planning is key to operational success. Photo U.S. Air National Guard

On the strategic and operational level, the war in Afghanistan clearly showed NATO’s deficiencies in the information environment, such as a lack of coordinated and integrated information efforts. It took another conflict to take the next step, and the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 was definitely a wake-up call for NATO in that regard. Shortly after the conflict started, NATO’s member states realized both the importance of disinformation in Russian doctrine and its effects on their domestic audiences. As a consequence, NATO officially adopted and implemented Strategic Communication, in order to better align strategy, action, and communication.[6]

On the tactical level, one could observe the increase and further development of military information capabilities, such as Psychological Operations. Countries like Germany have even organized similar capacities in a separate command, on the joint level, as another service of the military.[7] Moreover, doctrine has evolved significantly. In the context of conflicts below the threshold for lethal force, NATO has elevated information to a warfighting function, on the same level as Fires, or Command & Control, for example. The U.S. Army did this as well, not only ‘to provide the capabilities to influence adversarial actions outside of lethality’, but this change intends to ‘serve as a catalyst for the required institutional mindset change’.[8] Also in the Netherlands, the joint function information has been introduced into the latest Dutch doctrine.[9]

Now celebrating its 25th anniversary since its founding, 1 (German/Netherlands) Corps (1GNC) based in the German city of Münster, is one of NATO’s High Readiness Force (Land) Headquarters. It is able to deploy as a Corps Warfighting Headquarters, as NATO Response Force Land Component Command, or as Joint Task Force (Land) Headquarters. In addition, 1GNC acts as a professional training platform for divisions and brigades.[10] Within this context, 1GNC has developed its understanding on how to deal with the joint function information. As the authors both have been working on the information environment within 1GNC, they thought it timely to pass on what they had observed and learnt. To develop its ideas and concepts, 1GNC has experimented, learnt, and implemented Strategic Communication in its organisation and battle rhythm. The authors believe their headquarters (HQ) is in a favourable position to further develop information, given 1GNC has a breadth of expertise, staff capacity and experience with all information capabilities, and is continuously adapting its approach and procedures in the information environment. This is mirrored in the organisational structure itself, where the importance of the non-lethal environment is integrated and apparent from the outset of planning and subsequent execution.

Some argue that social media have reshaped conflict itself and that it is not about whose army wins, but whose story wins. Photo Rijksoverheid, Richard van Elferen

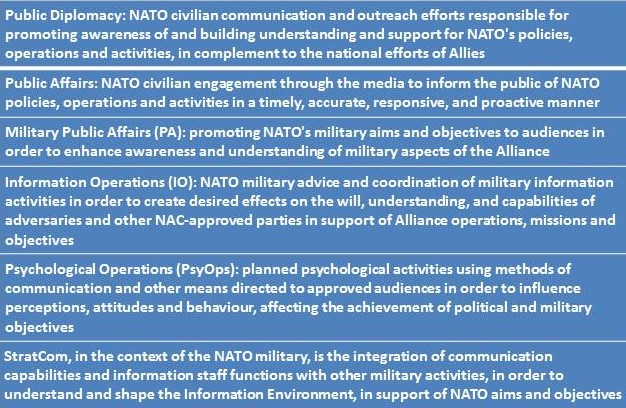

The central argument in this article is that the key to operational success (and especially in the information environment), on the tactical, operational, and strategic levels, entails a seamless and successful integration of information into military planning and application of operational art. As far as is possible within the context of a public article, strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities will be described. Subsequently, it will be discussed how 1GNC deals with the joint function information, including targeting, and how this played out during various exercises. To conclude, the authors will offer some reflections on what they have experienced over the last few years. However, as the doctrine and thinking about information in the military realm still suffer from a lack of broad common understanding, the article starts with providing some basic definitions of NATO’s activities, capabilities and effectors in this domain (see Table 1).

Table 1 Overview of definitions of NATO’s communication activities and capabilities[11]

Information within 1GNC

NATO doctrine provides us with a common philosophy, a common language, a common purpose, and a unity of effort, whilst Standard Operating Instructions provide further guidance. The key is that 1GNC’s headquarters structure follows NATO’s latest Military Policy on Strategic Communications (StratCom).[12] This policy sees StratCom moving from a purely advisory and coordination function, to that of holding the Commander’s delegated authority. StratCom in NATO is a command responsibility that spans all levels. It directs, coordinates, and synchronizes the overall communication effort and ensures coherence across the communication capabilities and information staff functions. This is often referred to as the ‘Golden Thread’.

In 1GNC, staff officers for StratCom, Information Operations (including Key Leader Engagement), Targeting, Electronic Warfare, PsyOps, and Military Public Affairs) are all grouped in one of the four divisions of the HQ, under a Deputy Chief of Staff for Communication and Engagement. This ensures their integration within the HQ’s operations analysis, planning, execution and assessment, in accordance with the commander’s intent and objectives. In contrast with NATO’s StratCom Policy, the Communication & Engagement division also includes the CIMIC (G9/J9) Branch. Experience has demonstrated that this ensures a comprehensive approach in all operations; a crucial perspective embedded in the DNA of 1GNC.[13]

The authors found that this organisational structure and grouping of several of these disciplines, including CIMIC, has generated a deeper understanding, more resilience, and better cross functional cooperation, both in the planning and execution of operations.[14]

Notably often only a higher tactical level like 1GNC has this breadth of expertise and capacity, with a few dozen different staff officers from various backgrounds; while divisions and brigades usually have limited means and capabilities to deal with challenges in the information environment. The high turnover of staff and specific subject matter expertise is, however, a training and continuity challenge, sometimes shared with other NATO staffs. But the nucleus remains sound, robust and fit for purpose.

Recent experiences with the information environment

It appears that there is never any shortage of direction and guidance from the strategic and operational levels on the ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of an operation, but focus at the tactical level also has to be on the ‘How?’, in order to achieve the Commander’s objectives. In essence, this is what Mission Command is all about. To quote a previous Commander of 1GNC, who at STARTEX was prone to say: ‘show me what you are doing, where are the actual products and make it tangible’. The last few years have provided realistic opportunities to the Professional Training Platform to conduct academics, Battle Staff Training and to test procedures at the German Army Warfighting Centre in Wildflecken and, of course, to make it tangible.

1GNC has refined its contributions during Crisis Response Planning with relevant input to operational plans and orders. Coupled with this has been the imaginative scripting of an enemy modus operandi that incorporates an effective Influence Campaign that demands a response from the military and others, in order to develop a common mindset that views the information environment as being inextricably linked to the physical environment.

1GNC’s Public Affairs officers participate in an exercise . Photo 1GNC

The Corps’ training audiences have not been virtual or abstract. Tempo, friction, fatigue, and pressure have often felt very real. There has been plenty of scope for ‘testing and adjusting’ within the HQs of 1 (DEU) Armoured Division and (DEU) Rapid Forces Division during Exercise Vital Sword in 2017. This also included many other multinational secondary training audiences and response cells, such as 11 (NLD) Air Manoeuvre Brigade and 43 (NLD) Mechanised Brigade. Further, as 1GNC was in the lead for the certification of the NRF 19 VJTF (L) Brigade (based on the 9 (DEU) Lehr Brigade in 2018), tangible progress could be measured.

1 (DEU) Armoured Division was once again put through its paces in 2019, during Exercise Xenon Sword, together with 13 (NLD) Light Brigade and 1 (NOR) Brigade North. Within the Area of Operations they were faced with hybrid threats and an unfolding humanitarian crisis that threatened to impact the operation. Examples include a displaced population clogging up lines of communication, the lack of basic needs for the civilian populace, and the enemy’s use of propaganda on exercise social media accounts, where the training audiences’ actions or indeed perceived mistakes and actions could be exploited. Throughout the build-up of the exercises, and detailed in the After Action Reviews, commanders at all levels displayed an increasingly firm grasp of the complexity and utility of the information environment. The blurring of the lines between war and peace and an enemy not following a familiar template were met with recognition and involvement of the Public Affairs Officer and Key Leader Engagement from the outset, with support from PsyOps, CIMIC, Electronic Warfare and other subject-matter experts, allowing commanders to incorporate many non-lethal effects in their planning and execution.

When combined in a Comprehensive Approach, commanders could tackle the complex scenarios and recognise that at the tactical level the preponderance of communication is achieved by what is actually done — rather than by what is said. However, the value of using ‘traditional’ messaging techniques, such as leaflet drops and radio broadcasts etcetera was also not dismissed, especially in those areas where civilian infrastructure was lacking. Many of the PsyOps products also proved the complexity of the information environment. To understand what it would take to defeat the enemy’s will to fight requires a thorough Target Audience Analysis.

Targeting

Targeting is a process of determining the effects necessary to achieve the commander’s objectives, and of identifying the actions necessary to create the desired effects based on means available. Furthermore, the process includes selecting and prioritising targets, synchronising fires with other military capabilities, and then assessing their cumulative effectiveness and taking remedial action, if necessary.[15] To many, this conjures up an image of precision-guided munitions being delivered onto targets from various platforms.

However, in every operation one must also be able to influence adversaries, the local population, or even attack enemy information capabilities and to protect one’s own information capabilities to affect enemy understanding. This realisation that being able to combine lethal and non-lethal effects with kinetic and non-kinetic means in the targeting process requires the right mindset and is often challenging for all members of the staff to understand.

Key in the approach of 1GNC is that its targeting process is aimed at achieving effects in all domains and all battlespaces, and integrates both lethal and non-lethal targeting in one and the same process. In this context, in 1GNC communication is often referred to as a ‘weaponeering’ solution. What has been observed is that this works well at Joint and Corps level, and incorporates target nominations at the Divisional and Brigade levels.

This implies that a number of Working Groups in the 1GNC Battle Rhythm leads to an Information Operations and Targeting Coordination Board, where timely decision-making on synchronisation of effects and means have helped in its conceptual development. The Target Approval process, like much else, requires practice and an understanding of the level at which delegations are held and where assets and expertise external to an HQ can play a role in the process through Liaison Officers. Many may also be struggling with the concept that a large number of the desired effects often require extensive planning. Moreover, it could also last many months before the effects of a messaging campaign could be observed in the behaviour of the local population.

Figure 1 1GNC’s approach to targeting: integration of both lethal and non-lethal targeting in one process

Experiences in Norway - Exercise Trident Juncture

An opportunity for putting into practice what had been learnt and conducting further experiments was the introduction to, preparation for, and delivery of Exercise Trident Juncture in 2018. This NATO-exercise in Norway included 50,000 participants, 250 aircraft, 10,000 vehicles, and 65 vessels from 30 nations. It was also a significant opportunity to be fully exploited for real-life StratCom effect in support of NATO objectives. An Integrated Communication Plan provided coherence with a focused ‘whole of NATO’ effort.

StratCom synchronisation was required both horizontally within the HQ, as well as vertically to ensure message coherence and to create a Golden Thread from the political/strategic to the lowest tactical level. To busy multinational staff officers, StratCom Frameworks with their key messages and narratives could be challenging to absorb at first sight. They required a healthy dose of distillation in order to be fully understood and implemented. The practice of summarising the essence of the frameworks was outlined on simple Participant Cards containing facts, such as troop numbers. However, in a dispersed command structure and in a multinational setting it was not always easy to exploit every phase of the exercise. Preparation, from Reception Staging and Onward Movement to Integration activity, should not be overlooked. The requirement, therefore, during Commanders’ conferences to confirm the StratCom Golden Thread must always be briefed. The Golden Thread provided a clear understanding of what NATO was trying to achieve, allowing for both a vertical and horizontal alignment at all levels of command. The requirement for operational security was also discussed in detail and practised. One such aspect are soldiers’ actions on social media and reliance on personal electronic devices. To assist in this education there are several good national examples that provide direction and guidance for the use of social media that have helped to shape behaviour and recognise the advantages and disadvantages of its use during operations and peacetime activities.

This exercise also exposed the limitations of conducting assessments of actions within the setting and relatively short duration of the CPX phase. Joint Targeting Coordination Boards with higher HQs and other Component Commands certainly synchronised the lethal and non-lethal effects. The resultant Battle Damage Assessments and Measurements of Effectiveness of a Deception Operation, which included radio messages, exercise social media, and leaflets to encourage enemy forces to surrender, for example, requires dynamic scripting to complete the Cycle and provide realistic feedback for the ensuing planning.

NATO exercise Trident Juncture provided opportunities to practice what had been learnt. Photo NATO

It also became clear that 1GNC’s own information activities caught the attention of the Joint Force Commander. Delegation of authorities such as Target Engagement and PsyOps Product Approval, which were thought to be clear from the outset, still created a healthy discussion concerning at what level they should be held, given that the effect of a dropped leaflet could outlast the impact of dropping a bomb.

In this exercise, the cooperation and the reach back capacities of the German Bundeswehr’s Zentrum Operative Kommunikation in Mayen proved to be very valuable. Recognition of their capabilities and experience coupled with frequent visits developed a fruitful exchange of ideas and techniques that could be applied in the form of sophisticated visual and audio products designed to degrade the will of NATO’s potential opponents.

The conundrum of operating in an exercise setting, whilst also cognisant of ‘real-life’ perception management, and profile and posture in the host country Norway (which was also very attuned to a real battle of the narratives), was instructive for NATO’s deterrence and reassurance measures.

The NATO Media and Information Centre, augmented with members of 1GNC PA, was well-resourced and prepared for its task. Media training prior to deployment was conducted, but perhaps this could have focussed on a wider cross-section of the staff to allow more junior officers and NCOs to tell their stories. After all, everyone is a communicator. The Norwegian Ministry of Defence provided daily reports throughout the exercise on how the exercise was perceived amongst the population over time, and was able to provide a genuinely positive measurement of effectiveness. The successful Distinguished Visitors Day near Trondheim sent a clear political message of NATO’s cohesion, whilst Sputnik and RT stories provided the predictable counter narrative. There were some good examples of this, but timely counter- messaging at the highest level with the intention to be the first out with the truth, and dispel fake news about where NATO-troops were exercising, troop numbers, the intent with the ‘Golden Thread’, and NATO’s cohesion underpinning this effort.

How to bring the outside world in?

1GNC has recognised and learnt that exercising in the information environment does not begin and end at the gates of Wildflecken, or when undergoing its own certification. In contrast with crisis response operations, which are limited in time and space, the information environment is omnipresent. In 1GNC, it is also considered ‘in peacetime’ how to assist in helping to shape the attitudes and behaviours of intended audiences. Instructive questions used were, for example, ‘How do we see ourselves and through what lens do external actors and audiences that matter most to us see us?’ And ‘how do we bring the outside world in?’ This sounds obvious, but some of us live in an information ‘comfort bubble’, often termed by others as the ‘echo chamber’. Many of us are often oblivious to the negative and subtle narratives being played out against us over time and the fact that objective facts are often less influential in shaping opinion that appeals to people’s emotions and personal beliefs.

In order to tackle this perceived lack of perception, 1GNC formed a peacetime Information Activities Working Group. It seeks to generate an information environment awareness across the staff, synchronise ideas, reflect on previous activity and look ahead to how 1GNC can improve and harness key events and activities that can create information effects. This should also build resilience and make the most of 1GNC’s reach on social media and through other outlets, whilst benefitting from a more nuanced analysis that seeks to send the message to the right audiences. Perhaps a good measure of effectiveness also includes how friends and families talk about what we all do?

The next steps, as 1GNC prepares for JTF HQ (L) certification in 2020 and its role as PTP for 10 (DEU) Armoured Division in 2021, will, however, include improving understanding of what is already available through Open Source, the NATO Multimedia library, national examples and regular communication with Centres of Excellence. The staff must continuously be sensitised to the importance of the information environment with the opportunities and threats it presents.

‘How do we see ourselves and through what lens do external actors and audiences see us?’. Photo U.S. Air National Guard

Reflection

In this article, the authors have shared their perspective on the information environment: how to understand it, how to synchronize information capabilities, and how to operate in this environment. Based on their experiences, these are some of their insights and reflections.

First, it must be stressed that any planning and execution in the information environment requires a thorough understanding and analysis of the specific and relevant information environment. Often, evidently these analyses are limited to what is currently happening, not continuously, restricted to the Western perspective, and limited to media-, web- and social media-monitoring. This is reinforced by the abundance and speed of information. However, in order to be successful, synthesis is paramount. What are the trends, and what do they mean? How does information affect attitude and behavioural patterns of different audiences? And where does this offer opportunities (and threats), especially at our level, and within our means and capabilities to act in the information environment? We have learnt that this depth of analysis, followed by deliberate planning and coordination, requires a significant amount of time, expertise and effort, which is not always available.

Over the years, the personnel at 1GNC have developed a mindset that enables leaders and staff to understand the information environment in the broadest sense, and train, plan, and act accordingly. This change took years, both practically and culturally. In hindsight, a prerequisite is a strong, professional force of specialists in the different communication disciplines. We were fortunate to work with these individuals and teams. However, they have usually received training or gained experience in only one of the career fields. Oversight does require insight; and building up the required level of expertise will require more experience on different levels and in different fields.

Relatedly, it does not help that this relatively new field of expertise suffers from an abundance of unclear, overlapping, or even a conflicting body of knowledge. The continuous development and implementation of new terms, and the conceptual nature of this field, does contribute to a lack of common understanding, both within the information-related disciplines and, more importantly, with other fields of expertise and senior leadership. New doctrine, like the upcoming NATO doctrine on StratCom will assist, but the military definitely needs a simplification of the terms, to make ‘outsiders’ better understand how to integrate information as a joint function into warfighting. In this context, the Dutch military could be clearer on its emerging concept of Information Manoeuvre as well; how and where does it add which relevant operational value and where does it overlap with the existing capacities, capabilities, and doctrine. The Dutch are not alone in this regard; a recent RUSI report, for example, argued that also the British Army should become more comfortable with working outside the purely military space, and with blending non-kinetic capabilities and effects with already existing and well-developed kinetic effects and capabilities.[16]

Conclusion

This article is built on experiences gained at 1GNC with others and shows that probably a key factor for successful operations is the amalgamation of information with other joint functions. In the crisis response planning phase of an operation, StratCom and other information capabilities planners should be involved in developing courses of action with the most advantageous likely outcomes. Becoming successful in the information environment is definitely not about ‘sprinkling information effects’ onto an existing plan. In the execution phase, it was found that Joint Targeting has proven to be most effective to synchronize actions and effects in all domains. Therefore, in a world where conflicts abound and where perceptions become reality, the key to operational success on the tactical, operational, and strategic levels is successful integration of information into military planning and application of operational art.

* Col dr. Joris van Esch is an officer in the Royal Netherlands Army, and now Deputy Chief of Staff Communication & Engagement at Headquarters 1 (German/Netherlands) Corps, Münster (Germany). Col Simon Hirst is an officer in the British Army, and until September 2020 Assistant Chief of Staff for Information Operations and Targeting in the same headquarters.

[1] Naomi Klein, No Logo: No Space, No Choice, No Jobs (London: Fourth Estate, 2010) iv.

[2] Michael J Mazarr et al., The Emerging Risk of Virtual Societal Warfare: Social Manipulation in a Changing Information Environment (Santa Monica, CA, RAND Corporation, 2019) 115.

[3] Carl von Clausewitz, On war, ed. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1976), 252.

[4] As an example, see the analysis on strategic narratives in the Afghan war in: Beatrice de Graaf, George Dimitriu, and Jens Ringsmose, Strategic Narratives, Public Opinion and War: Winning Domestic Support for the Afghan War (Routledge, Abingdon, 2015) 351.

[5] David Patrikarakos, War in 140 Characters: How Social Media Is Reshaping Conflict in the Twenty-First Century (New York, Basic Books, 2017).

[6] Neil MacFarquhar, ‘A Powerful Russian Weapon: The Spread of False Stories’, in: The New York Times, 28 August 2016; Mark Laity, ‘NATO and Strategic Communications’, in: The Three Swords Magazine 33 (2018) (9).

[7] ‘Kommando Cyber- und Informationsraum’.

[8] Charles M. Kelly, ‘Information on the Twenty-First Century Battlefield Proposing the Army’s Seventh Warfighting Function’, in: Military Review 100 (2020) (1) 66.

[9] Ministerie van Defensie, Nederlandse Defensie Doctrine, February 2019, 90.

[10] For more information on 1GNC, see https://1gnc.org.

[11] These definitions are shorter than (but similar to) definitions from official NATO doctrine: ‘About Strategic Communications’. The StratCom definition is derived from NATO MC0628. NATO Military Committee, ‘NATO Military Policy on Strategic Communications (MC0628)’, 14 August 2017. For official definitions, see the latest (respective) NATO doctrine documents.

[12] NATO MC0628.

[13] In addition, a senior official of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs is seconded to 1GNC, to advise on the civil and political aspects of an operation from a foreign policy and human security perspective.

[14] In line with the MC0628, Chief PA (the spokesperson) retains its independent advisory role and direct access to the Commander on Public Affairs matters.

[15] NATO Standard AJP-3.9 Allied Joint Doctrine for Joint Targeting, 2016.

[16] Nick Reynolds, ‘Performing Information Manoeuvre Through Persistent Engagement’, RUSI Occasional Paper, June 2020, 54.