Over the past two centuries, European strategic thinking has increasingly become more distant from classical conceptualizations of strategy. As a result, strategy is moving further and further away from its essential formative context: the battlefield. An exploration of the European strategic discourse shows a trend in which ambiguous and flawed concepts are becoming increasingly prominent, to the detriment of how people think about strategy and the distinction between war and peace. The popularity and acceptance of essentially non-strategic terms such as hybrid warfare and cyber war by Europe’s military and academic elite can be seen as the natural culmination of this trend. In an attempt to explain this development, this essay provides an overview of how European strategic thinking has become increasingly non-strategic over the last two centuries. James Sheehan’s thesis on the rise of the European civilian state can be used as a framework to explain this trend.

Timothy van der Venne, BSc*

In July 2016, NATO took a significant step in shaping how Europeans think about strategy when it recognised cyberspace ‘as a domain of operations in which NATO must defend itself as effectively as it does in the air, on land and at sea.’[1] In putting cyberspace on the same footing as air, land, and naval operations, NATO, either wittingly or unwittingly, removed strategic thought yet another inch farther away from its classical conceptualisation and, by extension, away from the battlefield.[2] In fact, the acceptance of cyberspace as a domain is inherently related to a trend in European strategic thought in which the very notion of strategy becomes increasingly muddled, with dangerous consequences for how we think about war and peace. In recent decades, the proliferation of ambiguous strategic concepts such as inter alia cyber war, hybrid warfare, grey-zone warfare, information war, and new wars among European defence analysts are testament to this trend.[3] All of these concepts put what used to be at the centre of strategy – a violent, kinetic conflict within the context of a war – on the backburner in favour of a far woollier conceptualisation of war and peace. This, in turn, dilutes what we perceive to be strategic and what we perceive to be warfare with potentially dangerous consequences.[4] This prompts the question: how did Western perceptions of strategy change over the last two centuries?

This essay argues that Western strategic thought has, especially since the end of the Second World War, moved the emphasis away from the battlefield and became increasingly non-strategic. To that end, this essay will first give an overview of how strategic thought developed from Clausewitz to the present in order to showcase this trend and become reacquainted with the classical meaning of strategy. Next, to demonstrate the contemporary culmination of this trend, this essay uses two popular strategic concepts to illustrate how strategic thought has become non-strategic: hybrid warfare and cyber war. Finally, with the aim of providing a preliminary explanation for this trend, this essay uses James Sheehan’s civilian state thesis to draw a line of comparison between Europe’s political history and its strategic thought.[5] This essay therefore uses a mixture of theoretical and empirical insights to formulate its arguments. It must be noted, however, that the focus lies on Western, specifically European, strategic thought – therefore, sources are limited to Western and European academic, think tank, and strategic documents.

In putting cyberspace on the same footing as air, land, and naval operations, NATO removed strategic thought farther away from its classical conceptualisation. Photo NATO CCDCOE

Strategy from Borodino to your laptop

Warfare is a timeless phenomenon, finding expression in the writings of old thinkers such as Sun Tzu, Kautilya, and Thucydides.[6] As such, thinking about strategy can certainly be traced farther down the line than to Clausewitz and the Napoleonic Wars – the very word for strategy (strategos) being an old Greek extraction meaning general.[7] However, while discussing the development of Western strategic thought it makes sense to start with Clausewitz, since his contribution to thinking about war and strategy is of such grand calibre that, it can be argued, there is no way to discuss contemporary Western strategic thought without reference to Clausewitz.[8] While the overview here presented is necessarily oversimplified and brief, this essay, in an attempt to illustrate how Western strategic thought has moved away from the battlefield, identifies three major phases in strategic thought that highlight this development:

- classical strategy, as developed during and after the Napoleonic Wars by thinkers such as Clausewitz and Von Moltke the Elder;

- grand strategy, as it developed during the First and Second World Wars, and

- all-inclusive strategy, as it developed in the decades after the Second World War, culminating in today’s predicament.[9]

Classical strategy as developed by Clausewitz and Von Moltke is taken as the starting point, since their work is consistently viewed as the foundation stone of modern strategic studies by the field’s foremost theorists.[10] Clausewitz’s view of strategy is firmly focused on the conduct of war – on the actual battlefield. It is most succinctly summed up as follows: ‘strategy forms the theory of using battles for the purposes of the war.’[11] In fact, Clausewitz’s vision of strategy looks mostly like the contemporary view of the operational level of strategy: it is the purview of the military commander in the field who is tasked with ‘the use of the engagement for the purposes of the war.’[12] Von Moltke the Elder, in turn, affirms the centrality of violent conflict by stating that ‘[strategy] is the application of sound human sense to the conduct of war.’[13] This classical approach to strategy thus has several key factors that influence how we think about warfare: (1) violent conflict – ‘using battles’[14] – is central, and (2) violence has an instrumental quality – ‘for the purposes of the war’.[15] The Clausewitzian approach to strategy thus gives clear primacy to the military duel on the battlefield.[16] This purely military view of strategy remained dominant until the outbreak of the largest, most destructive wars in human history.

Strategy’s purview was then expanded beyond the military dimension. Grand strategy was born out of the most cataclysmic events in military history: the First and Second World Wars.[17] The existential, all-encompassing nature of these conflicts means that the making of strategy and how to conduct wars had to adjust to a grander scale. As Gray notes: strategy refers to the use of military instruments, while grand strategy ‘embraces all the instruments of statecraft.’[18] So, whereas classical strategy places the military commander as the primary actor in charge, grand strategy more distinctly envelops the civil-military divide: strategy-making becomes an issue for both the political and military leadership.[19] It entails coordinating the military instrument with the economic, diplomatic, and social instruments a state has at its disposal.[20] The most important factor justifying the inclusion of non-military tools in strategy was the existential nature of the First and Second World Wars: the scale of death and destruction meant that the very survival of the state was at stake, legitimising the use of all instruments of state power in order to achieve victory – to survive.[21] The misapplication of the Clausewitzian concept of total war shows this period’s grave existential nature.[22] During this destructive period, warfare touched every layer of civil society – its impacts went far beyond the military dimensions of warfare as every aspect of civil society was mobilised for the purposes of the war.[23] In Europe, according to Gray, ‘[two] total wars dominated’ the first part of the twentieth century, effectively elevating strategy beyond the battlefield to include the mobilisation and coordination of non-military, civil elements.[24]

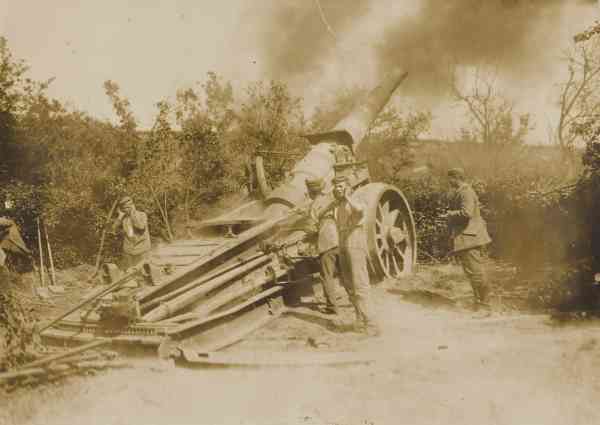

German artillery during World War I in Deinze, Belgium; the purely military view of strategy remained dominant until the outbreak of the most destructive wars in human history. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Since 1945, however, strategic thinking has fallen victim to an all-inclusive view of strategy. The inclusion of non-military tools into strategy – justified as it may have been during the existential threats of the two world wars – has since placed strategy increasingly farther away from its contextual origins: violent conflict.[25] Strategy since 1945 is first marked by nuclear weapons, but nuclear strategy in itself focuses specifically on the non-conduct of war, concentrating on avoiding war rather than waging it, stimulating the trend away from the battlefield.[26] Moreover, in the decades since the end of the Cold War, Western military actors have adopted concepts into their doctrines that consistently favour non-kinetic measures: hybrid warfare, cyber war, and grey-zone warfare are prime examples.[27] In doing so, measures that have traditionally been viewed as part-and-parcel of international competition (i.e. espionage, energy diplomacy, economic measures) suddenly take precedence, while those aspects which classically take centre-stage in strategy – the military dimension – are downplayed.[28] The very meaning of strategy therefore becomes dislodged from its original conceptualisation, moving it away from the battlefield to such an extent that every non-military aspect of international competition can be viewed as a strategic imperative.[29] This all-inclusiveness can have dangerous consequences, as the discourse within European strategic circles reflects: the lines between what constitutes war and peace become blurred and threats that used to fall under generic competition are seen as warfare.[30] By including any and all acts under the strategic umbrella, European strategists risk sleepwalking into dangerous situations.

In sum, Western strategic thought exhibits a clear trend towards inclusiveness, risking the dilution of how we think about strategy – and what we perceive to be warfare. In canvassing the development of Western strategic thought since Clausewitz, this essay identifies three key phases: classical strategy, in which the violent conduct of war is central; grand strategy, which includes the mobilisation and coordination of military and non-military tools to achieve victory, and all-inclusive strategy, which gives non-military tools pride-of-place in strategy. The battlespace thus also expanded from a geographic area to be violently contested to a non-material domain such as cyberspace. Two concepts which gained notable traction in European strategic circles can be viewed as the logical culmination of this trend towards non-strategic thinking: hybrid warfare and cyber war.

Strategizing non-strategic matters

As the previous section shows, Western strategic thought has, in the past two centuries, become increasingly inclusive. Strategy has moved from a matter reserved for generals to a matter reserved for statesmen.[31] Strategic studies since the end of the Cold War especially have seen the emergence of concepts which place the conduct of war, classically a central pillar of strategy, on the backburner in favour of a far woollier sense of what constitutes war and peace, and thus what constitutes a strategic imperative.[32] European military actors, think tanks, and academia have since coined, spread, and adopted concepts into their strategic lexicons which are at best strategically unsound and at worst non-strategic.[33] The two recent buzzwords hybrid warfare and cyber war can be seen as the natural culmination of that trend. Both concepts have become popular among military actors in recent years, and both concepts favour non-military tools and a confusing view of what can be considered warfare.[34] The following section outlines how Europe’s strategic community came to accept these terms in order to illustrate the contemporary culmination of the trend toward a non-strategic conception of strategy.

Started as a purely military concept developed by Frank Hoffman (centre), hybrid warfare quickly expanded into something primarily non-military. Photo U.S. Naval War College, Rosalie Bolender

Hybrid warfare

Hybrid warfare has seen a development of increasing inclusion similar to the trend described above. It started as a purely military concept developed by Frank Hoffman, inspired by the 2006 Second Lebanon War, but quickly expanded into something primarily non-military.[35] Hybrid warfare refers broadly to the convergence of various modes and modalities of warfare; it foresees a compression of levels and methods of war into one conflict where actors fluidly shift gears between conventional and irregular methods, intensity levels, and actor type.[36] In Hoffman’s view, hybrid warfare was a distinctly military strategic concept, but after the 2014 Russo-Ukrainian War, hybrid warfare shifted towards a non-military focus.[37] European analysts, dazzled by Russian actions in Ukraine, suddenly began including and emphasising the perceived focus of hybrid warfare on the social, informational, and economic tools Russia uses, rather than the military context in which they were used.[38] As such, hybrid warfare became a concept that refers more to generic international competition rather than to an approach to warfare: the coordinated use of diplomacy, economic measures, cyber tools, and information campaigns in the international arena take the spotlight, rather than the military context needed for classical strategy.[39] The nature of hybrid warfare as a strategic concept was thus quickly diluted.

Europe’s defence community, however, framed Russian actions in Ukraine as a completely new way of waging war and the concept gained such momentum that hybrid warfare popped up in the doctrinal documents of the EU, NATO and its constituent members.[40] Exploring the European discourse on hybrid warfare, one sees that European think tanks such as the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), Chatham House, and the The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (HCSS) have published numerous articles on so-called hybrid warfare, almost all of which do not focus on the military context, but on the perceived uses of hybrid warfare in international competition.[41] Further catalysing its popularity, institutions such as the Swedish Defence University, Dutch counter-terrorism organisation NCTV, and other European national security institutions published strategic documents on hybrid warfare which all emphasise non-military tools in a non-military context.[42] So it appears that European awe in the face of Russian action in Ukraine resulted in a vast over-interpretation of hybrid warfare, leading European analysts to conceptualise hybrid warfare as something which has very little to do with actual warfare. The result is that European strategists accepted a concept into their thinking which is only minimally strategic in the classical sense. Strategy is again moved further away from the battlefield and, paradoxically, into non-violence.

Cyber war

Another term which has proved immensely popular among European defence officials is the conceptually unsound denomination cyber war. The adoption of cyber war as a term into contemporary European strategic discourse epitomises, in this author’s view, the trend in strategic thinking to see non-strategic issues as strategic. The first reason for this is the conceptual paradox inherent in the term.[43] The second is the persistent use of cyber war in spite of this by prominent European defence officials.[44]

Cyber war refers succinctly to the possibility of war taking place in cyberspace.[45] While recent developments in cyber have proven time and again that cyber tools can indeed have an impact upon a state’s stability – e.g. the Stuxnet hack, the NotPetya hack – the likelihood of a cyber war happening is minimal.[46] When discussing the (lack of) conceptual usefulness of a term like cyber war, one need only look at the term’s last part: war. Thomas Rid, in his influential article and subsequent book, both titled ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’, outlines how war, according to Clausewitzian theory, must involve an act of force which is ‘violent, instrumental, and political.’[47] Rid goes on to show that cyberattacks, by their very nature as non-violent, often non-attributable, and indirect acts, cannot live up to those criteria.[48] Put simply, cyber war cannot exist because acts of warfare, which are violent by their very essence, cannot be carried out in cyberspace. Similarly, the acceptance of cyberspace as a domain of war implies that acts of violence can occur in cyberspace, which is patently not the case: cyberattacks use cyberspace as a medium to inflict damage rather than a domain in which to inflict it.[49] Militarising cyberspace, and adopting cyber war as a strategic concept, therefore introduces the paradoxical notion that strategy can exist where war cannot, once again including something inherently non-strategic under the umbrella of strategy.

The adoption of cyber war as a term into contemporary European strategic discourse epitomises the trend in strategic thinking to see non-strategic issues as strategic. Photo Ohio National Guard, George Davis

The academic community, following Rid’s example, repeatedly demonstrated the logical fallacy of cyber war, but Europe’s defence community still persistently uses the term, directly influencing European strategic thought.[50] Notably in the Netherlands, where former Minister of Defence Ank Bijleveld stated that ‘the Netherlands is in a state of cyber war with Russia,’[51] a statement backed up by former Dutch Chief of Defence Lieutenant Admiral Rob Bauer.[52] In line with this view, the Dutch government has invested significantly in defence-related cyber capacities, even offering ‘cyber soldiers’ to NATO, showing that the Netherlands is basing its force posture on the cyber war concept.[53] However, when pressed for the specifics of this cyber war, Bijleveld mentions Russian interference in elections,[54] while Bauer refers to acts of cyberespionage,[55] neither of which reaches the Clausewitzian thresholds for war and neither of which are matters of classical strategy.[56] In fact, according to their own examples, so-called cyber war is more akin to traditional intelligence operations than to the conduct of war.[57] The Netherlands defence community is thus a prime example of how issues which are not strategic by nature come to be included into Europe’s common strategic lexicon, while having very little bearing on the waging of actual war. The implications of using such terms are potentially dangerous.

The language of war matters

Hybrid warfare and cyber war both take inclusiveness to such a high level so as to water down the very meaning of war and strategy. Two factors make these concepts the natural culmination point of the trend in European strategic thought away from the battlefield: firstly, each of these factors places reduced emphasis on the actual conduct of war, traditionally a core pillar of strategy, favouring non-violent, non-military tools, and secondly each takes an ambiguous approach to what constitutes warfare. The European defence community, as illustrated, uses both these terms persistently in their doctrines, strategic visions, and public statements.[58] This essay argues that this puts European strategists at risk of sleepwalking into dangerous situations because it no longer understands the difference between war and peace.[59]

After all, the language which we use to describe phenomena matters. Terms like hybrid warfare and cyber war are concepts that do not describe acts that are clearly acts of war. Instead, as Stoker and Whiteside note, these terms are used ‘in the opposite sense, as a way to describe a supposed new way of war that deliberately blurs the lines between war and peace’.[60] As such, they are not strategic concepts, but non-strategic concepts. Blurring lines between war and peace might be all the rage in contemporary strategic studies but doing so means that states, with considerable power to create or destroy global stability, increasingly use the language of war in situations where it is not appropriate.[61] If everything is viewed as an act of war, it becomes more difficult for strategists to level-headedly ascertain proportional responses without the risk of going overboard. The trend towards inclusiveness in strategic thought, therefore, has a dangerous edge to it. Returning to a more classical understanding of strategy might help, as Stoker and Whiteside conclude, ‘not to confuse geopolitics, competition among adversaries, or influence efforts with war.’[62] However, it is also important to understand how European strategic thought got to this point. This essay proposes that James Sheehan’s civilian state thesis might serve as an explanatory framework for the overarching trend in European strategic studies that veers increasingly away from the battlefield.[63]

From military to civilian state, from strategic to non-strategic

Europe’s political history and its strategic thought are inherently linked, with each influencing the other in a circular dynamic. In his elegant and solemn account of Europe’s destructive twentieth century entitled The Monopoly of Violence, James Sheehan argues that Europe’s political and military history over the course of the previous century ensured the rise of the civilian state: a state made by, and for the benefit of, peace as opposed to Europe’s 19th century states which were more explicitly focused on war.[64] Sheehan’s thesis proceeds along two central arguments: that the perceived obsolescence of war is not a global phenomenon, but a distinctly European one which comes as the direct result of Europe’s cataclysmic events of the 20th century; and that the disappearance of war on the European mainland after the Second World War created a new kind of European state: a civilian state marked by social rather than military values.[65] This argument shows a clear overlap with the development in European strategic thought outlined above. This essay therefore argues that Sheehan’s civilian state thesis can be used as an explanatory framework to illuminate how Europe’s strategic thought increasingly distanced itself from actual warfare. Because European societies distanced themselves from war, they distanced themselves from an understanding of what strategy entails. To illustrate this, this section draws a line of comparison between Sheehan’s thesis and the development as sketched previously.

Shaped by the Napoleonic Wars, European strategists based their strategic thinking on where conflicts are decided: on the battlefield. Photo ANP/TASS, Sergei Fadeichev

First, the age of classical strategy can broadly be seen as Europe’s default outlook on strategy until 1914. European states in the 19th century were premised on the capacity to wage war. As Sheehan states: ‘[war] was deeply inscribed on the genetic code of the European state.’[66] Sheehan describes how war and military experience were considered a central and natural part of life for millions of Europeans, giving military institutions a key role to play in how society was organised.[67] Shaped by the Napoleonic Wars, the prime contributors to the classical conceptualisation of strategy – Clausewitz, Von Moltke, and Jomini – all have their roots in this martial Europe.[68] For European states in this period, war was instrumental; it was a legitimate way to decide political conflicts between states, in which what happened on the battlefield was generally accepted by all involved.[69] It is thus natural to see how, being firmly anchored in the conduct of war, European strategists based their strategic thinking on how war is waged and where conflicts are decided: on the battlefield. However, developments in how 19th century European societies planned for war had a direct impact on how war would be waged in the 20th century.[70]

Second, the nascent grand strategy as it developed during ‘Europe’s Long War’ (1914-1945) was foreshadowed by developments in the 19th century. As European societies democratised, so did the waging of war: the creation of mass reserve armies alongside massive technological developments during the 19th century meant that the scale of war would grow exponentially.[71] As the First and Second World Wars show, the contested battlespace was no longer a field, but vast regional, geographic areas. With great feeling, Sheehan describes how this increased scale, alongside the existential nature of the Long War conspired to bring about a level of carnage unparalleled in military history.[72] In turn, strategy was elevated from fighting on a singular battlefield to the level of planning for a global war of survival. The growth and democratisation of European societies thus again had a direct impact on how strategy is perceived.

Third, the end of the Long War brought about two changes that precipitated the time of all-inclusive strategy: European trauma and resulting distaste for war, as well as the rise of the United States as a structural hegemon.[73] The European experience during the Long War was one of annihilation and inhumanity, forever dispelling the allure of militarism among its citizens.[74] The rise of the US as Europe’s security provider further meant that Europeans no longer had to engage in the use of force. These factors ensured that Europeans would rebuild their societies as ‘states without war’, civilian states focused on welfare and social values while shunning all things martial.[75] The same two factors Sheehan identifies as actuating the rise of the civilian state can also be viewed as catalysing the trend in European strategic thought farther away from the conduct of war. No longer faced with the necessity of dirtying their hands with warfare, Europeans outsourced matters of defence to the US while focussing on non-military development.[76] As such, Europeans unlearned how to think strategically in favour of how to think economically and socially. The inclusion of economic and social factors into strategic concepts such as hybrid warfare and cyber war showcases this deficiency. Europe’s civilian state thus has a critical weakness: its neglect of military values over the past century has weakened its strategic awareness, contributing towards a trend in European strategic thought away from violence.

A French pilot during NATO’s Baltic Air Policing mission, 2020; in unlearning martial values, Europeans also unlearned how to think strategically. Photo NATO

Conclusion

In unlearning martial values, Europeans also unlearned how to think strategically. European strategic thought in the past two centuries went through a development analogous to the development of the European state: trending increasingly farther away from the actual conduct of war, focusing instead on non-military matters of competition. Sheehan’s civilian state thesis illustrates how developments in Europe’s 20th century political history effectively ‘banished international violence from the European society of states’ and forms a fitting explanatory framework to examine the changes in European strategic thought.[77] Propelled by developments in European societies and in how to wage war, this essay identified three phases in European thinking about strategy since Clausewitz: classical strategy, which has its roots in 19th century martial Europe, grand strategy, which emanated from the global, existential scale of what Sheehan terms Europe’s Long War (1914-1945), and all-inclusive strategy, which includes and even favours non-military means. This overview displays an overarching tendency to expand, becoming increasingly inclusive to the point of eliminating that which has traditionally been at the centre of strategy: the conduct of war. As such, strategic thought in Europe has become increasingly non-strategic. The widespread acceptance of two ambiguous concepts, namely hybrid warfare and cyber war, into Europe’s strategic lexicon exemplify this development.

The implications of this are potentially dire. In using the language of war to describe situations which are generally seen as part-and-parcel of international competition, European strategists risk sleepwalking into dangerous situations. States still have considerable power to shape global stability and blurring lines between war and peace makes it far more difficult for those in power to determine proportional responses to threats. In order to offset this danger, Europe’s strategic community would benefit from reacquainting itself with classical interpretations of strategy and ought to be very wary of allowing terms into the strategic lexicon which have little bearing on the actual conduct of war.

* Timothy van der Venne holds a BSc in Security Studies from Leiden University and is currently a postgraduate student and Saltire Scholar of the MLitt Strategic Studies programme at the University of St Andrews. He has interned with the Royal Netherlands Air Force (130SQN/KMSL) and has co-authored policy briefs for NATO’s Emerging Security Challenges Division.

[1] NATO, ‘Cyber defence’. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_78170.htm (updated July 2, 2021).

[2] Carl von Clausewitz, On War (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1976) 177; Hew Strachan, ‘The lost meaning of strategy’, Survival 47 (2005) (3) 33-54; Thomas Rid, ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’, Journal of Strategic Studies 35 (2012) (1) 5-7; Isabelle Duyvesteyn and Jan Angstrom, Rethinking the Nature of War (London, Routledge, 2005).

[3] John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, ‘Cyberwar is Coming!, Comparative Strategy 12 (1997) (2) 141-165; Hew Strachan, The Direction of War. Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013) 10-25; Hugo Klijn and Engin Yüksel, ‘Russia’s Hybrid Doctrine: Is The West Barking Up The Wrong Tree?’, Clingendael Monitor, November 28, 2019. See: https://www.clingendael.org/publication/russias-hybrid-doctrine-west-barking-wrong-tree ; Murat Caliskan, ‘Hybrid Warfare through the Lens of Strategic Theory’, Survival 60 (2019) (6) 73-90; Donald Stoker and Craig Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines: Gray-Zone Conflict and Hybrid War – Two Failures of American Strategic Thinking’, Naval War College Review 73 (2020) (1) 19-54.

[4] Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 3; Hew Strachan, ‘Strategy in Theory; Strategy in Practice’, Journal of Strategic Studies 42 (2019) (2) 171-190.

[5] James Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence. Why Europeans Hate Going to War (Chatham, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2007) xviii-xx.

[6] Lawrence Freedman, Strategy. A History (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013) 1-65; David Jordan et al, Understanding Modern Warfare, 2nd Edition (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2016) 21-79; Strachan, The Direction of War, 1-45.

[7] Robert B. Strassler, The Landmark Thucydides. A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War (New York, Free Press, 1996); Freedman, Strategy, 72-75.

[8] Colin S. Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 2nd Edition (London, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005) 17-33; Bart Schuurman, ‘Clausewitz and the ‘New Wars’ Scholars’, Parameters 40 (2010) (1) 89-100; M.L.R. Smith, ‘Strategy in an Age of ‘Low-Intensity’ Warfare. Why Clausewitz is Still More Relevant than his Critics’, in: Duyvesteyn and Angstrom, Rethinking the Nature of War, 28-51; Timothy van der Venne, ‘Misreading Clausewitz. The Enduring Relevance of On War’, E-International Relations (2020), see: https://www.e-ir.info/2020/02/04/misreading-clausewitz-the-enduring-relevance-of-on-war/.

[9] Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 1-347; Freedman, Strategy, 1-572.

[10] Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 17-33; Freedman, Strategy, 82-96; Strachan, The Direction of War, 46-63.

[11] C. von Clausewitz, Strategie aus dem Jahr 1804 mit Zusätzen von 1808 und 1809 (Hamburg, Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt, 1809) 62.

[12] Clausewitz, On War, 177.

[13] Daniel Hughes, Moltke on the Art of War. Selected Writings (New York, Presidio Press, 1993) 124.

[14] Clausewitz, Strategie, 62.

[15] Clausewitz, On War, 177.

[16] Clausewitz, On War, 177-181, 236-237, 605-610.

[17] Lukas Milevski, ‘Grand Strategy and Operational Art: Companion Concepts and Their Implications for Strategy’, Comparative Strategy 33 (2014) (4) 342-353; Basil Liddell Hart, When Britain Goes to War. Adaptability and Mobility (London, Faber & Faber); Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 211.

[18] Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 1.

[19] Strachan, ‘Strategy in theory; strategy in practice’, 171-190; Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 211.

[20] Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 1, 211.

[21] Idem, Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 211; Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, 69-144.

[22] Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 68, 141-143.

[23] Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 141-143; Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, 69-144.

[24] Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 141

[25] Strachan, The Direction of War, 10-25, 253-282; Freedman, Strategy, vii-xvi; Thomas Mahnken and Joseph Maiolo, Strategic Studies. A Reader, 2nd Edition (New York, Routledge, 2008).

[26] Freedman, Strategy, 145-155; Gray, War, Peace, and International Relations, 231-244.

[27] Caliskan, ‘Hybrid warfare through the lens of strategic theory’, 40-58; Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 19-54; The Military Balance 2015. The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London, International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2015).

[28] Caliskan, ‘Hybrid warfare through the lens of strategic theory’, 40-58; Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 23-26; Gregory Treverton et al, ‘Addressing Hybrid Threats’ (Stockholm, Swedish Defence University, 2018), see: https://www.hybridcoe.fi/publications/addressing-hybrid-threats/.

[29] Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 23-26; Strachan, The Direction of War, 10-25, 253-282.

[30] Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 19-54; Bettina Renz and Hanna Smith, Russia and Hybrid Warfare. Going Beyond the Label (Helsinki, Aleksanteri Institute, 2016), 1-23; Chimaira. Een duiding van het fenomeen ‘hybride dreiging’ (Den Haag, Nationaal Coördinator Terrorismebestrijding en Veiligheid, 2016) 1-34.

[31] Strachan, The Direction of War, 10-45; Strachan, ‘The lost meaning of strategy’, 33-54; Freedman, Strategy, ix-xvi.

[32] Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 12-16, 23-26.

[33] Caliskan, ‘Hybrid Warfare through the Lens of Strategic Theory’, 40-41; Strachan, ‘The lost meaning of strategy’, 33, 40-52; Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 12-16, 23-26.

[34] Rid, ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’, 5-7; Caliskan, ‘Hybrid Warfare through the Lens of Strategic Theory’, 40-41; Klijn and Yüksel, ‘Russia’s Hybrid Doctrine’.

[35] Frank Hoffman, ‘Hybrid Warfare and Challenges’, Joint Force Quarterly 52 (2009) (1) 34-39; Caliskan, ‘Hybrid Warfare through the Lens of Strategic Theory’, 46-49.

[36] Hoffman, ‘Hybrid Warfare and Challenges’, 34, 36-37.

[37] Caliskan, ‘Hybrid Warfare through the Lens of Strategic Theory’, 46-49.

[38] Caliskan, ‘Hybrid Warfare through the Lens of Strategic Theory’, 46-49; Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 16-26.

[39] Caliskan, ‘Hybrid Warfare through the Lens of Strategic Theory’, 40-58; Treverton et al., ‘Addressing Hybrid Threats’, 9-12; Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 23-29.

[40] Sascha Bachmann and Hakan Gunneriusson, ‘Russia’s Hybrid Warfare in the East. The Integral Nature of the Information Sphere’, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 16 (2015) 198-211; Ofer Fridman, Russian ‘Hybrid Warfare’. Resurgence and Politicisation (London, Hurst & Company, 2018) 11-45; Caliskan, ‘Hybrid Warfare through the Lens of Strategic Theory’, 40-41, 46-49;

[41] IISS, The Military Balance 2015, 115; Keir Giles, Russia’s ‘New’ Tools for Confronting the West. Continuity and Innovation in Moscow’s Exercise of Power (London, Chatham House Russia and Eurasia Programme, 2016) 2-3; Frank Bekkers, Rick Meessen and Deborah Lassche, Hybrid Conflicts. The New Normal?’ (Den Haag, TNO and HCSS, 2018), see: https://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Hybrid-conflicts.-The-New-Normal-HCSS-TNO-1901-_0.pdf.

[42] Treverton et al, ‘Addressing Hybrid Threats’, 9-12; NCTV, Chimaira, 1-34; Caliskan, ‘Hybrid warfare through the lens of strategic theory’, 46-49.

[43] Rid, ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’, 7-27; Sergei Boeke and Dennis Broeders, ‘The Demilitarisation of Cyber Conflict’, Survival 60 (2018) (6) 73-90.

[44] Alexander Martin, ‘NATO prepares for world’s largest cyber war game – with focus on grey zone’, SkyNews (April 13, 2021), see: https://news.sky.com/story/nato-prepares-for-worlds-largest-cyber-war-game-with-focus-on-grey-zone-12274488 ; Peter Visser, ‘Commandant der Strijdkrachten Bauer: ‘Nederland moet zich beter verdedigen tegen cyberaanvallen’’, WNL (October 11, 2020), see: https://wnl.tv/2020/10/11/commandant-der-strijdkrachten-bauer-nederland-moet-zich-beter-verdedigen-tegen-cyberaanvallen/

[45] Rid, ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’, 7-10.

[46] Rid, ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’, 5-7, 27-29; Lawrence Freedman, Ukraine and the Art of Strategy (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2019); Treverton et al, ‘Addressing Hybrid Threats’, 53-56.

[47] Rid, ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’, 10.

[48] Idem, 10-16.

[49] Michael Kreuzer, ‘Cyberspace is an Analogy, Not a Domain: Rethinking Domains and Layers of Warfare in the Information Age’, The Strategy Bridge (July 8, 2021), see: https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2021/7/8/cyberspace-is-an-analogy-not-a-domain-rethinking-domains-and-layers-of-warfare-for-the-information-age.

[50] Rid, ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’, 5-32; Kreuzer, ‘Cyberspace is an Analogy, Not a Domain’; Boeke and Broeders, ‘The Demilitarisation of Cyber Conflict’, 73-90; Martin, ‘NATO prepares for world’s largest cyber war game’; Visser, ‘Commandant der Strijdkrachten Bauer’.

[51] ‘Defensie-minister Bijleveld: ‘Nederland is in cyberoorlog met Rusland’’, WNL (October 14, 2018), see: https://wnl.tv/2018/10/14/cyberoorlog-met-rusland/.

[52] Visser, ‘Commandant der Strijdkrachten Bauer’.

[53] WNL, ‘Defensie-minister Bijleveld’.

[54] Idem.

[55] Visser, ‘Commandant der Strijdkrachten Bauer’.

[56] Clausewitz, On War, 75-89, 177-183, 577-578; Rid, ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’, 7-16.

[57] Boeke and Broeders, ‘The Demilitarisation of Cyber Conflict’, 74-79.

[58] Caliskan, ‘Hybrid warfare through the lens of strategic theory’, 46-49; Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 16-29; NCTV, Chimaira, 1-34; IISS, The Military Balance 2015, 115; WNL, ‘Defensie-minister Bijleveld’

[59] Stoker & Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 23-26.

[60] Idem, 23.

[61] Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 23-26; Renz and Smith, ‘Russia and Hybrid Warfare’, 1-4, 11-13.

[62] Stoker and Whiteside, ‘Blurred Lines’, 3.

[63] Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, xviii-xx.

[64] Idem, 172-197.

[65] Idem, xvii-xx.

[66] Idem, 7.

[67] Idem, 7-21.

[68] Clausewitz, On War, 3-25, 27-58; Hughes, Moltke on the Art of War, 1-19; Strachan, The Direction of War, 46-63. Freedman, Strategy, 69-95.

[69] Strachan, The Direction of War, 26-45; Freedman, Strategy, 69-95

[70] Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, 7, 20-21, 91.

[71] Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, 7-21; Gray, War, Peace and International Relations, 75-89, 100-112, 130-139, 141-143.

[72] Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, 69-143, Gray, War, Peace and International Relations, 141-143.

[73] Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, 147-171; Tony Judt, Postwar. A History of Europe since 1945 (London, Vintage Books, 2005) 13-40.

[74] Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, 170-171; Judt, Postwar, 13-14.

[75] Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, 145, 170-171.

[76] Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, 170-171, 172-197; Judt, Postwar, 1-10, 701, 716-717

[77] Sheehan, The Monopoly of Violence, xvii.