By February 2016, the EU had been trying for months to cope with an increasingly desperate refugee crisis stemming from the civil war in Syria, raging since March 2011. Nerves in Brussels and the national capitals of the EU countries were stretched, and it was felt that there would be a renewed upsurge in the refugee flows as soon as weather improved in Spring. Stories about migrants crossing from Russia into Finland and Norway in 2015 and early 2016 further fuelled the sense of a deliberate strategy. Many feel that the refugee crisis may have weighed heavily on public opinion in the UK in the run-up to the Brexit referendum. In order to explore the allegations against Moscow, it is necessary to analyse what Russia did in support of the Assad regime in Syria. Did Russia’s actions indeed worsen the migrant crisis in the EU?

Hans Schoemaker MA*

In February and March 2016, when the refugee crisis facing the European Union was still ongoing and vivid in the minds of European politicians as well as the public, US General Philip Breedlove, Head of NATO forces in Europe, accused Russia of working actively to exacerbate the refugee flows in an attempt to destabilize and destroy the EU. In a testimony in front of the House Armed Services Committee, he said, ‘Together, Russia and the Assad regime are deliberately weaponizing migration from Syria. In an attempt to overwhelm European structures and break European resolve.’[1]

This accusation did not fall into a vacuum. By February 2016, the EU had been trying for months to cope with an increasingly desperate refugee crisis stemming from the civil war in Syria, raging since March 2011. Although the world would later realise that the refugee crisis had already peaked by then, nerves in Brussels and the national capitals of the EU countries were still stretched, and it was felt that there would be a renewed upsurge in the refugee flows as soon as weather improved in Spring. Stories about migrants crossing from Russia into Finland and Norway in 2015 and early 2016 – sometimes using a legal loophole by crossing by bike – further fuelled the sense of a deliberate strategy.[2] Many feel that the refugee crisis may have weighed heavily on public opinion in the UK in the run-up to the Brexit referendum in June.

lthough Breedlove’s accusation found some support among security mavens, it was largely left unchallenged in the media and political arenas, especially considering how severe the allegations were. This article explores the allegations in order to determine their merit and, in doing so, fill the gap in the response. It will do so by examining the allegations themselves, the response they evoked, and the general circumstances: an examination of the actual events in Syria and the EU. In particular, this paper addresses the following questions: firstly, what did Russia do in support of the Assad regime in Syria, and, secondly, did its actions significantly worsen the migrant crisis in the EU? An analysis of what we know caused the peaks and troughs in the refugee crisis has been included. Furthermore, answers will be sought to questions such as whether Russia deliberately targeted civilian populations in Syria, and whether it was with the intent to exacerbate the refugee crisis resulting from Syria's civil war and to target the EU and its member states?

It should be noted that there is evidence Russia has used the refugee crisis for political purposes, in so far that the Kremlin seeks to leverage the political cleavages in the EU through propaganda and influencing campaigns. An example of this is the alleged rape case of a 13-year old German-Russian girl, known as Lisa F., who claimed to have been raped for 30 hours on end after being kidnapped by migrants which, German authorities said, never happened.[3] However, this paper’s scope is to address only the allegations of causing the refugee flows in order to attack Europe.

The allegation

On 25 February 2016, General Philip Breedlove, Supreme Allied Commander of NATO and Commander of the United States European Command, gave his last testimony before the United States House of Representatives Armed Services Committee. Shortly before retiring from his command as well as from the military Breedlove was asked to provide his views on the European security situation. Europe, he said, faces threats from two sides: a resurgent Russia to the East, and a complicated migration crisis triggered by the inability of states in the Middle East to provide security to their populations to the South. Exacerbating this wave of migration is Islamic State, which ‘is spreading like a cancer’,[4] displacing millions in Syria and Iraq, and thereby creating an unprecedented refugee crisis. Framing it as Hybrid Warfare, he then added, ‘Russia and the Assad regime are deliberately weaponizing migration from Syria. In an attempt to overwhelm European structures and break European resolve.’[5]

Breedlove stated: ‘… I am seeing in Syria in places like Aleppo and others […] what I would call absolutely indiscriminate, unprecise bombing rubblizing (sic) major portions of a city. That do not appear to be -- to me to be against any specific military target because the weapons they’re using have no capability of hitting specific targets. They are unguided dumb weapons. And what I have seen in the Assad regime from the beginning when they started using barrel bombs which have absolutely no military utility. They are unguided and crude and what are they designed to do (sic) is terrorize the public and get them on the road. Later, Assad using chlorine gas and other chemical type approaches to these same barrel bombs. Again, almost zero military utility. Designed to get people on the road and make them someone else’s problem. Get them on the road, make them a problem for Europe to bend Europe to the will of where they want them to be. And so I see a continuing pattern in Aleppo and other places of this indiscriminate use of military capability that all I can determine from it is the goal is to get more people on the road and make them a problem for someone else to bend the will of those being affected.’[6]

General Philip Breedlove speaks to the press about the complex security situation in Europe, shortly after his testimony to Congress. Photo US Army, Clydell Kinchen

Five days after this, Breedlove gave the same statement – nearly verbatim – before the Senate Armed Services Committee. In neither case did he provide evidence supporting his conviction on the intentions of Russia and Syria beyond his belief that is was corroborated by the indiscriminate nature of the targeting as applied by Russia and Syria. Furthermore, unlike at other moments during his two briefings, when he offered to follow up on specific questions with a classified briefing at a later stage, he does not extend this offer for his accusation about Russian and Syrian weaponized migration.

Breedlove’s comments resonated with Senator John McCain, a veteran of the Vietnam War and Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, who had laid the same accusation at the feet of Russia only two weeks earlier at the 2016 Munich Security Conference. Speaking to an audience of politicians and security leaders there, he said: ‘Mr Putin is not interested in being our partner. He wants to shore up the Assad regime, he wants to re-establish Russia as a major power in the Middle East, he wants to use Syria as a live fire exercise for Russia’s modernizing military, he wants to turn Latakiyah province into a military outpost from which to harden and enforce a Russian sphere of influence, a new Kaliningrad or Crimea, and he wants to exacerbate the refugee crisis and use it as a weapon to divide the transatlantic alliance and undermine the European project.’[7]

At the Senate hearing of Breedlove, McCain asked the retiring general if he believed that the Russians are using the refugee issue as a means to break up the EU. Again Breedlove explained his reasoning: ‘These indiscriminate weapons used by both Bashar al Assad and the non-precision use of weapons by the Russian forces I cannot find any other reason for them other than to cause refugees to be on the move and make them someone else’s problem.’[8] At his earlier testimony, when asked by Senator Tom Cotton if the break-up of the EU and NATO are long-term goals of Putin, Breedlove answered that he believes this to be one of Putin’s ‘primary goals’.[9]

The response

Despite the seriousness of the allegations, careful screening of the literature presented no well-founded studies on the subject. There are a number of commentaries, op-eds, and lectures by academics reacting in a more ad-hoc way to the accusations, without being based on thorough study. Most take the accusation at face value and provide some context.[10] In the media, the response was also muted. The main international outlets picked up the statements by General Breedlove, but few went further than placing it in the broader context of the refugee crisis.[11] The same was the case with the allegations by Senator John McCain, which were picked up by a number of outlets without sparking more in-depth coverage.[12] A rare exception was a longer editorialized article in The Economist.[13] It is somewhat puzzling to see this lack of interest, as compared to the continued scrutiny awarded to other incidents involving (alleged) Russian aggression, such as election interference in the US, and later in France, or the assassination attempt with a chemical weapon on former Russian spy Sergei Skripal in the UK. This is especially remarkable, given the fact that it is hard to see the alleged actions of Russia and Syria as anything less than a casus belli.

Russian and Syrian forces stand guard near posters of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin at the Abu Duhur crossing in Idlib province, 2018. Photo ANP/AFP, George Ourfalian

Weaponized migration

Allegations of weaponized migration lead straight to the work of Kelly Greenhill, who has coined the phrase and provided a large body of work on the subject, consisting of a book published in 2010 and around half a dozen papers on the subject.[14] The links but also the gap between her work and the allegations are evident.

Greenhill defined the concept of weaponized migration in 2008 as ‘the manipulation of population movements as operational and strategic means to political and military ends.’[15] She distinguishes between four forms of strategic engineered migration:

1. Dispossessive, meant to dislocate populations in order to appropriate their territory

2. Exportive, which either seeks to strengthen control of an area, or, conversely, loosen control of an area held by a foe by flooding it with refugees

3. Militarized, which disrupts or destroys command and control of a foe by displacing its personnel, or denying access to infrastructure, or possibly overwhelming its military structures

4. Coercive, with actuated or threatened outflows used to extract a certain behaviour from the adversary.[16]

Greenhill has identified over one hundred cases of the phenomenon since 1951, implying that the weaponization of strategically engineered migration is relatively common.

However, Greenhill’s framework neither describes engineered migration as a means of Hybrid Warfare, nor fits the case of Russia engineering refugee flows to destabilize the EU. Variant 1, Dispossessive, is not applicable at all, as Russia has no designs for taking the houses or land of displaced Syrians. The other variants are problematic in their own right. In the case of Exportive, the intention of Russia and Syria could indeed be to strengthen control over the areas they are targeting; in fact this is a likely reason for aggressive targeting. By dislodging the population from urban areas, they can subsequently engage hostile militias without any lingering concern about collateral damage. However, that is a method of warfare against the insurgents, not against the EU. In order to count towards that aim, Russia would have to believe it can affect the strength of governance of areas which refugees flee to. The size of the refugee flows – although of historic proportion with around 1 million Syrians fleeing to Europe – cannot be expected to truly affect governance in this extremely rich part of the world with over 500 million inhabitants, especially considering the fact that far higher numbers had no such effect in countries in the vicinity of Syria. Lebanon, which has some 6 million inhabitants, hosts over 1 million Syrian refugees,[17] the highest share of refugees per capita in the world. In Jordan, a country with 9.7 million inhabitants, there are around 650,000 Syrian refugees, the second highest share.[18] In similar proportion, the EU would have to face a flow of over 80 million refugees.

The third form of strategic engineered migration Greenhill has identified is militarized, in which a refugee flow is meant to disrupt or destroy military capabilities in a region, either by depopulation or by overwhelming numbers on the move, depending on the direction of the flow. Again, it may be the case that the outflow of populations in areas controlled by insurgents, such as Islamic State, is a strategic aim of the Syrian and Russian forces. Guerrilla type forces often depend on local civilians to provide part of the logistic support needed to maintain fighting strength. However, to suggest that 1 million dispersed refugees could disrupt the fighting strength of European nations is an enormous stretch of the imagination.

If it was Russia’s intention to use refugees as a means of coercion and getting sanctions relief from the EU, it has not worked. Photo US Air National Guard, Cheresa Theiral

The fourth form of strategically engineered migration identified by Greenhill is coercive, based on an aversion to newcomers from either ethno-nationalist, economic, or strategic considerations, in order to extort concessions. This form seems to have limited local applicability, as the militias would not be overly bothered by migration flows into their areas as such. This variant might have more traction in the case of the EU, where particular member states have shown a lot of aversion to taking in even small amounts of refugees. However, there is no coercion without demands, and there have not been any, at least not publicly acknowledged. Even if discussions were held behind closed doors, it should be noted that the grand prize, sanctions relief, did not come to pass, so even if Russia intended to coerce the EU like this, it has not worked.

Displacing populations in Syria may have had certain strategic or tactical benefits for the Syrian and Russian forces in the fight against insurgents. Its usefulness in trying to topple the EU, on the other hand, is clearly lacking. As such, the displacements – insofar as deliberate – may fit Greenhill’s model, but their use as a weapon against the EU is shown to be an unlikely motive.

Hybrid Warfare

Breedlove explicitly linked the weaponized migration allegations against Russia to a broader context of Hybrid Warfare by Moscow. This term, however, even though it is widely used among academics and policy makers, is misleading and unhelpful. A survey of the literature on Hybrid Warfare, a relatively new favourite of security studies, also shows there is little to no direct examination of the weaponization of migration or refugee crisis and – as said – no serious study of the allegations that lie at the heart of this paper. Hybrid Warfare as a concept, as well as its derivatives, has become such a mainstay in security studies in the last few years, that it is easy to overlook that it does not have a fully established definition.

The term Hybrid Warfare has been around at least since 2005, when it was used by James Mattis and Frank Hoffman to describe an ‘unprecedented synthesis’ of ‘the traditional, the irregular, the catastrophic, and the disruptive.’[19] The original meaning of hybrid was that of blended political-military threats, but was primarily seen as supporting conventional assets in the context of kinetic conflicts.[20] However, the meaning has shifted over the years from mixed tactics in open, asymmetrical war towards conflicts ‘below the level of armed conflict.’[21]

It was the intervention of Russia in the Ukraine in 2014 that triggered the shift in meaning in recent years, argues Keir Giles. ‘The hybrid phraseology became firmly embedded in NATO’s conceptual framework for characterizing Russian operations in Ukraine, and as a result is now permeating the doctrine and thinking of NATO member states.’[22] Apart from that, in order to cover all of Russia’s geopolitical activity since, the concept has been stretched and no longer has a lot of utility, he adds. In fact, the concept has ‘emerged as a catch-all description of the new Russian threat to European security.’[23] Likewise, Bettina Renz laments the trend of academics and policy-makers to increasingly use ‘Hybrid Warfare’ to describe Russia’s foreign policy in general, rather than just military doctrine, something that can potentially cause miscalculation and escalation.[24]

Increasingly, the academic consensus seems to be that Hybrid Warfare is simply the latest term to describe ambiguous warfare, which in itself is not new, and a ‘rather simplistic observation.’[25] As the understanding – if not the academic definition – of Hybrid Warfare seems to shift more and more to describing any (quasi) deniable activity below the threshold of armed aggression, such as disinformation, anti-democratic interference, et cetera – in other words anything that Russia can be credibly accused of – the earlier understanding that the ‘hybridity’ refers to a mix of conventional and unconventional tactics, seems to have fallen by the wayside.

President Putin meets his Turkish counterpart Erdogan: the concept of ‘hybrid’ has been broadened to incorporate nearly all of the geopolitical activities by Russia. Photo DPA/Picture Alliance

What remains then, is that Hybrid Warfare appears to have become the latest term for covert action. Consider the official US definition of covert action: ‘…the term ‘covert action’ means an activity or activities conducted by, or on behalf and under the control of, an element of the United States Government to influence political, economic, or military conditions abroad so that the role of the United States Government is not intended to be apparent or acknowledged publicly.’[26] Rand Corporation’s Christopher Chivvis lists the means and methods of Russia’s Hybrid Warfare toolkit, including information operations, cyber weapons, the use of pro-Russian proxies, economic influence such as gas diplomacy, exploitation of espionage to target vulnerable politicians abroad, and the use of special forces, and more traditional political influencing, always with the backdrop of Russia’s conventional and nuclear capabilities.[27] In comparison, there is not much that fundamentally divides the US definition and Chivvis’s list.

The concept of ‘hybrid’ has thus been broadened on the one hand, to incorporate nearly all of the geopolitical activities by Russia, and deepened on the other, to extend to nearly any type of unconventional aggression or threat and no longer refers specifically to a mix of conventional and unconventional tactics. And whereas academia appear to be approaching consensus of opinion that the very construct of hybrid is neither very helpful nor very informative, policy professionals continue to use the term and prioritize the policy area. It is the threat of hybrid that is a key focus in the newly found rapprochement between the EU and NATO. Following a Joint Declaration in 2016 by the leaders of the European Council, the European Commission, and NATO,[28] ‘common sets of proposals’ were approved by the EU and NATO Councils.[29] Of these (eventually) 74 proposals for cooperation, 20 focus on countering hybrid threats.

The afore-mentioned debate and policy-makers’ fascination does little to increase our understanding of geopolitical realities. Instead, it tends to obscure or displace more important considerations, such as how to respond to a broad-spectrum threat posed by a strategic adversary. Consider, for example, Chivvis, who proclaims that ‘Russian hybrid strategies pose a clear challenge to US national interests in NATO unity, a prosperous EU, and a strong liberal democratic system in Europe.’[30] By focussing on the ‘hybrid’ nature of the threat, comments like these act to mystify what amounts to non-deniable covert action. It also amplifies the perceived threat and gives said adversaries, often Russia or Islamic State, an aura of power that is disproportionate to reality.[31] According to Cormac and Aldrich, ‘NATO, and western commentators more broadly, see Russian subversion behind every gooseberry bush and fear that Putin is already waging hybrid warfare against eastern Europe, if not the whole of NATO.’[32]

Charap likewise cautions against the feverish excitement of some commentators in describing this ‘new’ threat, as well as against the danger inherent in the prevailing views of the same commentators, such as Chivvis: ‘Russian strategists believe that the US is willing to risk conducting a limited, hybrid operation in Russia – that is, on the territory of a nuclear power – just as NATO strategists believe Russia is willing to risk the same on the territory of a nuclear alliance.’[33] For example, Oliker et al, argue that as long as Putin or his inner circle remain in power, the relations between Russia and the West will continue to be affected by his fear of encroachment by liberal democracy and Western institutions – the EU and NATO – and Russia will attempt ‘within its capabilities, to keep them at a distance and, opportunity, weaken and undermine them, including through force of arms.’[34]

Over 5 million people have fled Syria since 2011, seeking refuge in Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and the EU. Photo MCD, Eva Klijn

Timeline of the Syrian civil war and refugee crisis

The following section examines if there is evidence of actus reus (‘guilty act’) for the accusations. To this end, this paper will anchor a few key moments in the Syrian civil war and refugee crisis against a timeline of the refugee flows.

In March 2011, bolstered by events across the Arab world, protests started in Syria to demand the release of a number of political prisoners. Security forces reacted heavy-handedly, killing a number of protesters. With the ensuing violence between – initially secular – revolutionaries and government forces the displacement of people started in May. Over 5 million people have fled Syria since then, seeking refuge in Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and the EU, while millions more were displaced internally. And without trying to shift blame away from the Syrian regime and Russia, engaged in a particularly brutal campaign against the insurgents, it should not be forgotten that the country has at some point been subject to airstrikes by the US, France, the UK, Israel, Turkey, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and others. Large parts of the country were under the yoke of Islamic State for years, whereas other parts were controlled by Al-Qaeda groups, such as Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (formerly Jabat Al-Nusra). It cannot hold that Russian/Syrian aggression is the only factor in generating refugee flows.

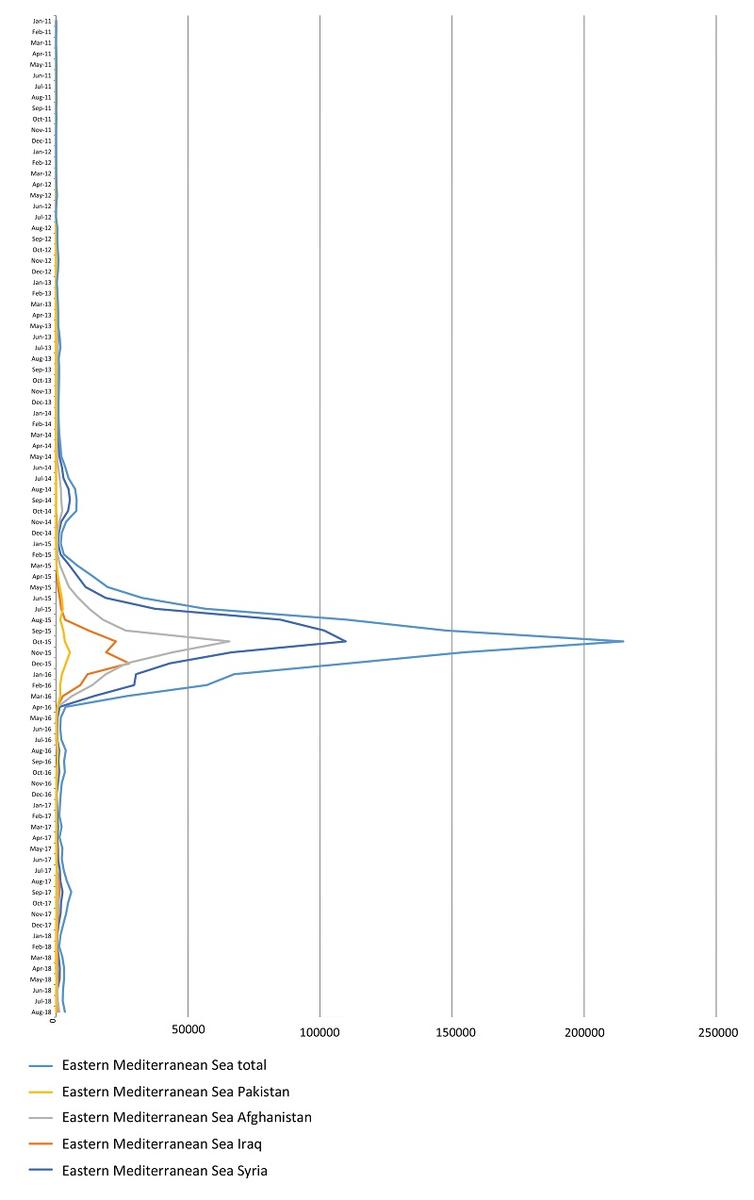

Figure 1 Migration flows from January 2011 to August 2018. Source: Frontex

When examining the data in figure 1 – in this case from Frontex – it becomes quickly evident that even if the allegations against Russia were true, they largely came after the facts. By February 2016, when the allegations were uttered, the peak of the crisis had decidedly passed. The entry into the Syrian theatre by Russian forces on 30 September may have resulted in a significant upsurge in refugee flows, but the trend at that point had already been established. Certainly October saw the highest number of border-crossings of any time during the crisis; however, the average time it took Syrian refugees to reach the Western Balkans Route was 21 days.[35] If this Russian bombing campaign had really led to a major movement of people, it would have been likelier that the bulk of this became more evident later but, as noted earlier, the peak came in October and passed. In fact, as one year later the full brunt of Russian military capability was brought to bear against Aleppo, in particular between 19 September 2016 after a ceasefire had been cancelled, and 18 October 2016 when Russia called an end to aerial attacks,[36] this was barely registered in terms of crossings of the Aegean Sea, as we can see in the Frontex data. One reason this had so little impact was the gradual closure by Turkey of its land border with Syria, starting in March 2015 and ending with a complete closure in early February 2016. What also stemmed the flow of refugees was the introduction by Turkey of visa requirements for Syrians, on 8 January. The argument could be made that it was then merely circumstance that thwarted Putin’s designs to target the EU through a refugee wave, but it seems unlikely that he was unaware of this. The fact that he continued to target civilian areas for months, particularly in Aleppo, indicates that generating a refugee flow towards the EU was not a primary consideration.

Mens rea

Next, this paper will examine the fundamental principle of (international) criminal law, namely the concept of mens rea - or ‘guilty mind’. To be sure, proving intent is exceptionally difficult, but evidence can be sought and found. Concerning the reasons why Russia got involved in Syria, there are a number of stated and perceived possibilities in the public domain. First and foremost, Putin attempts to prop up Bashar al-Assad’s position, and he has said as much.[37] Additionally, Moscow exports arms to Syria and maintains military bases in Tartus and Hmeimim.[38] In the next section follows an examination of the choice of methods and means of warfare. Within International Criminal Law, intent is provided for by Art. 30 of the Rome Statute, which stipulates criminal responsibility exists only when acting with intent and knowledge, meaning the person meant to engage in the conduct, or – in relation to a consequence – that person either meant to cause it, or knew it would occur ‘in the ordinary course of events.’[39]

Kristalina Georgieva, member of the EC in charge of International Cooperation, Humanitarian Aid and Crisis Response, announces 100 million euros of humanitarian funding for Syrian refugees and displaced persons, 2013. Photo European Commission

The first issue is to establish intent in the context of targeting, in other words, did Russia intend to target civilians, and did it intend to displace them? In this respect, the allegations seem to have some truth in them. Particularly in the case of the Battle of Aleppo (2012-2016) President Putin appears to have taken a page from his strategy manual for the Second Chechen War (1999-2000). Rather than a side-effect of a heavy-handed response to insurgency, argues Vignal, ‘destruction is not only a consequence of war but is central to the regime’s strategy.’[40] Mark Galeotti equally points at extreme levels of destruction, and draws a parallel with the capital of Chechnya in the Second Chechen War: ‘Putin is playing by Grozny Rules in Aleppo’ with the goal to break morale of the uprising and convince insurgents ‘that resistance is both futile and lethal.’’[41]

On the intent to displace: one cannot inflict such levels of destruction on urban areas without either a desire to cause – or the knowledge it would likely cause – an exodus; in fact this may be part of the strategy. By moving civilians out, insurgents lose the ability to hide among them, to benefit from an existing infrastructure and resources, and to use civilians as a human shield. However, evidence of targeting civilians – even when overwhelmingly present – is not sufficient to ‘prove’ that the secondary intent – to create a refugee crisis in the EU – exists. In order to establish a solid case of ‘weaponized migration’, the refugee flows should not be a side effect, but a clear, specific intent additional to the general intent of harming non-combatants through indiscriminate targeting. For the allegations to stick, it is necessary that there is the intention to use the result of this targeting strategy to cause a further effect, namely the destabilisation of the EU in this particular case. However, here the facts on the ground cannot be overlooked. Where the supposedly desired effect is absent, but the behaviour is the same, the question arises if the desire was ever there. As discussed earlier, the effect on the refugee crisis in the EU by Russia’s actions in Syria was no longer relevant by February 2016, if ever it had been before. Yet the Russian campaign in Syria is ongoing to this day.

Conclusion

This paper neither attempts to exonerate Russia’s behaviour in Syria, nor does it seek to justify it. It is the author’s opinion that Russia and the Syrian regime are committing atrocities that amount to war crimes. They do so recklessly and by willingly targeting civilian populations with a heinous disregard for key principles of International Humanitarian Law, including distinction and proportionality. In the end, evidence of this disdain for collateral damage does not equate to evidence of the intent to exacerbate the refugee crisis in order to strike at the European Union. As argued in this paper, there is scant evidence of this intent, except for the assertions of Senator McCain and General Breedlove.

Abandoned life jackets at a beach in Lesbos, Greece: there is evidence that Russia may have caused a portion of the refugee flow towards Europe. Photo Frontex

Upon examination of the available evidence, it can be said that the accusation of Russia weaponizing the refugee crisis in order to destabilise the EU cannot be maintained. Although there certainly are elements in Russia’s actions in Syria that may serve as evidence for the allegations, and are therefore not baseless but, at the same time, presuppose a lot. The line of argumentation used by General Breedlove in particular is as follows: Russia indiscriminately targets insurgents and civilians alike, apparently attempting to displace the populations from the active theatre, presumably in order to motivate these internally displaced persons to take to the road, hopefully overwhelming the closed borders of Turkey, go beyond Turkey and moving on to the EU, in an assumed plot to undermine the EU. The only evidence presented by Breedlove is that he sees no direct military objective for the methods of war employed by Russia and Syria against the insurgent factions in Syria. This paper has shown that there are a number of possible other motives for Russia to engage the way it does, and others could still be imagined. It also established that the supposed desired effect was not really achieved as the peak of the refugee crisis in October 2015 certainly came after the Russian intervention in Syria on 30 September, but not by much, and subsequent campaigns were waged without much impact on the refugee flows. This lack of supposed success reduced neither the intensity of Russia’s campaign, nor its brutality, and as such, generating migration flows was likely not a primary consideration for the intervention, nor was it a key driver for its continuation.

In conclusion, thus, there is evidence that Russia may have caused a portion of the refugee flow towards Europe, and was happy to exploit this for propaganda purposes. However, it was at most a side effect of their ‘normal’ approach to the kind of destructive war they have also waged previously, not a central element of their campaign, and not a key driver of the migration crisis, which was well underway when Russia jumped in, and in fact diminished in months to come despite the brutal campaign continuing unabated.

* Hans Schoemaker is an official at the Council of the EU, where he works on the Integrated Political Crisis Response arrangements (IPCR). He was the Official with Primary Responsibility for the Council in the 2018 EU NATO Parallel and Coordinated Exercise (PACE). The views expressed in this article are those of the author and in no way reflect the views of the Council or European Council.

[1] P.M. Breedlove, Gen. Breedlove’s hearing with the House Armed Services Committee in Washington D.C., (2016a) 3.

[2] H. O’Rourke-Potocki, ‘Finland and Norway tangle with Russia over migrants’, in: Politico, 25 January 2016; A. Korteweg, ‘Hekwerk moet Noorse grenzen behoeden voor fietsende vluchtelingen’, in: de Volkskrant, 25 August 2016.

[3] Andreas Rinke and Paul Carrel, ‘German-Russian ties feel Cold War-style chill over rape case’, Reuters, 1 February 2016.

[4] Breedlove (2016a) 3.

[5] Ibid, 3.

[6] Ibid, 12.

[7] J. McCain, Recording of Statement by John McCain at the Munich Security Conference 2016 (2016, 03m49s).

[8] P.M. Breedlove, 'Hearing To Receive Testimony On United States European Command' (2016b), 17.

[9] Breedlove 2016a, 75.

[10] E.g. P. Roell, Migration – A New Form of ‘Hybrid Warfare’? (Berlin, Institut für Strategie- Politik- Sicherheits- und Wirtschaftsberatung ISPSW, 2016).

[11] E.g. L. Dearden, ‘Russia and Syria ‘weaponising’ refugee crisis to destabilise Europe, Nato commander claims’ in: The Independent (3 March 2016); E. Randolph, ‘France razes migrant camp as Greece seeks EU aid’, Agence France Presse (1 March 2016); T. Watkins, ‘NATO commander says Russia, Syria using migrant crisis as weapon’, Agence France Presse (1 March 2016).

[12] E.g. C. Charlton, ‘Russia is deliberately escalating refugee crisis by bombing civilians... and using them as a weapon against the West, claims US senator John McCain’, in: MailOnline (15 February 2016); A. Cowburn, ‘Vladimir Putin ‘making refugee crisis worse to undermine Europe’’, in: The Independent (2 February 2016).

[13] ‘Vladimir Putin’s war in Syria: Why would he stop now?’, in: The Economist (20 February 2016).

[14] E.g. K.M. Greenhill, ‘Extortive engineered migration: asymmetric weapon of the weak’, in: Conflict, Security & Development 2 (2002) (03); K.M. Greenhill, ‘Strategic Engineered Migration as a Weapon of War’, in: Civil Wars 10 (2008) (1); K.M. Greenhill, Weapons of mass migration: forced displacement, coercion, and foreign policy (Ithaca, New York, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs, 2010); K.M. Greenhill, ‘Migration as a Weapon in Theory and in Practice’, in Military Review (June 2015).

[15] Greenhill, ‘Strategic Engineered Migration as a Weapon of War’, 7.

[16] Greenhill, ‘Extortive engineered migration’; Greenhill, ‘Strategic Engineered Migration as a Weapon of War’; Greenhill, Weapons of mass migration; Greenhill, ‘Migration as a Weapon in Theory and in Practice’.

[17] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Lebanon (Geneva, 2017).

[18] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Jordan (Geneva, 2018).

[19] J.N. Mattis and F. Hoffman, ‘Future Warfare: The Rise of Hybrid Wars’, in: US Naval Institute Proceedings, 131 (2005) (11) 1.

[20] M. Galeotti, ‘Hybrid, ambiguous, and non-linear? How new is Russia’s ‘new way of war’?', in: Small Wars and Insurgencies 27 (2016a) (2); Mattis and Hoffman, ‘Future Warfare’.

[21] J.N. Mattis, ‘2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States Summary, 11’ (2018) 6.

[22] K. Giles, Russia’s ‘New’ Tools for Confronting the West. Continuity and Innovation in Moscow’s Exercise of Power (London, Chatham House, 2016) 6.

[23] S. Charap, ‘The Ghost of Hybrid War’, in: Survival 57 (2015) (6) 51.

[24] B. Renz, ‘Russia and ‘hybrid warfare’’, in: Contemporary Politics 22 (2016) (3).

[25] R. Cormac and R.J. Aldrich, ‘Grey is the new black: covert action and implausible deniability’, in: International Affairs 94 (2018) (3); Renz, ‘Russia and ‘hybrid warfare’’.

[26] US Congress, Intelligence Authorization Act (Washington, D.C., 1991) sec 503.

[27] C.S. Chivvis, Understanding Russian ‘Hybrid Warfare’ And What Can Be Done About it (Santa Monica, Rand Corporation, 2017).

[28] European Council, European Commission, and NATO, Joint Declaration by the President of the European Council, the President of the European Commission, and the Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization Warsaw, 2016).

[29] Council of the European Union, Council conclusions on the Implementation of the Joint Declaration by the President of the European Council, the President of the European Commission and the Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (Brussels, 2017).

[30] Chivvis, Understanding Russian ‘Hybrid Warfare’, 10.

[31] Cormac and Aldrich, ‘Grey is the new black’.

[32] Ibid, 491.

[33] S. Charap, ‘The Ghost of Hybrid War’, in: Survival 57 (2015) (6).

[34] O. Oliker, C. Chivvis, K. Crane, O. Tkacheva, and S. Boston, Russian Foreign Policy in Historical and Current Context (Santa Monica, Rand Corporation, 2015) 25.

[35] International Organization for Migration, Analysis: Flow Monitoring Surveys (2016).

[36] Human Rights Watch, Russia/Syria: War Crimes in Month of Bombing Aleppo (2016).

[37] ‘Vladimir Putin Addresses Russia’s Intentions in Syria’, CBS News (24 September 2015).

[38] ‘Russia to extend Tartus and Hmeimim military bases in Syria’, Deutsche Welle (26 December 2017).

[39] UN General Assembly, 'Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (last amended 2010)' (1998)Art. 30.

[40] L. Vignal, ‘Destruction-in-progress: Revolution, repression and war planning in Syria (2011 onwards)’, in: Built Environment 40 (2014) (3) 326.

[41] M. Galeotti, ‘Putin Is Playing by Grozny Rules in Aleppo’, in: Foreign Policy (29 September 2016).